To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Implement peacemaking processes

This topic takes you through the different peacemaking processes you can use in your organisation, community or nation to manage or resolve conflicts, disputes and complaints.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- What peacemaking strategies does your group have in place?

- Are there areas where these could be improved?

- Why are formal policies and procedures important for effective peacemaking?

- What is culturally legitimate peacemaking?

- Are there ways you can make your peacemaking processes more culturally legitimate?

- How could you tailor peacemaking strategies to meet the needs of your group or wider community?

Designing your peacemaking processes

To practice peacemaking successfully, your group needs to have suitable and effective processes.1Helen Bishop, Aboriginal Decision making, problem Solving and Alternative Dispute Resolution – Challenging the Status Quo, in: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indigenous Communities (ADRIC) Symposium, 27 July 2015, Melbourne, 5. Processes should guide how your group addresses conflicts, disputes and complaints. They provide a roadmap to identify the cause of the conflict, dispute or complaint and outline what steps should be taken to manage or resolve it.

In this Toolkit, peacemaking processes include all forms of conflict, dispute and complaint resolution and management processes. The term ‘conflict’ often refers collectively to conflicts, disputes and complaints.

“You need rules [for peacemaking] just like the rules for sharing out a turtle. Everyone knows what they are. The way to get back those rules for peacemaking is by doing it every day. Then talk about it and get better at it. You just do it and do it and people will get used to it.”

– Yangkaal man, in Brigg, Memmott, Venables and Zonday, 20172Morgan Brigg, Paul Memmott, Philip Venables and Berry Zondag, “Gununa peacemaking: informalism, cultural difference and contemporary Indigenous conflict management,” Social & Legal Studies 27, no. 3 (2017): 357, [link]

Effective peacemaking processes generally set out:

- who should be involved

- roles, rights and responsibilities of those involved

- procedures, actions and/or options

- how to carry out communication and discussion

- what cultural knowledge to consider

- timeframes

- requirements for documenting the process and outcomes.

To have clear peacemaking processes in place, your group should consider what might happen in the future. This better equips you to resolve or manage conflicts, disputes and complaints.

Peacemaking is most successful when everyone involved has a sense of ownership over the processes and the rights of those involved are protected. Everyone should understand what they are entitled to. This involves people understanding:

- what happens and in what order

- the objective of each process – for example, what is being negotiated, or what people will make decisions about

- how everyone involved feels about the process

- their right to free, prior, and informed consent to each process and agreement

- when to say no to any processes or agreements

- how to manage and own their decisions and disputes.

Many of the organisations applying to the Indigenous Governance Awards have developed specific processes for dealing with conflicts, disputes or complaints. Communities or nations can also use these processes.

1. Clarify the issues

Approach the person or people directly involved. If needed, put the conflict, dispute or complaint in writing or document through a translator.

2. Maintain good communication

Take time to communicate with all parties involved. This includes communicating about their issues, rights, interests and options.

3. Rulebook or constitution

Organisations should use their rulebook or constitution as a guide to resolve conflicts, disputes or complaints with members.

4. Keep records

Document your processes in full. Include the solutions attempted and the outcomes. Share the relevant details widely in a way that’s easy to understand and accessible. Keeping good records helps keep people accountable. It also helps establish what went wrong if the same issues happen again. One way of doing this is by setting up a central complaints register. This could be a document that outlines all the complaints your group receives and the steps taken to address them. This allows you to track the complaint through different stages.

5. Use cultural processes

Where relevant, look at cultural processes for resolving conflicts, disputes or complaints that your group has used. This could include:

- referring to a council of Elders or advisory board

- using the influence of a particular kinship, ceremonial or gender-based form of authority.

6. Use external mechanisms

If the conflict, dispute or complaint remains unresolved, external mechanisms can help. For example, using an agreed mediator or referring to a representative body or non-government organisation with peacemaking expertise. This could include pro-bono legal firms.

7. Stay up to date with legislation

Make sure you know the legal requirements of the situation, so you can work towards a solution that follows the law. This might mean getting advice from a lawyer or other expert. If you are an incorporated organisation, make sure you understand and comply with any relevant industry or other requirements when dealing with complaints from members. For example, recent changes to the CATSI Act require that Prescribed Body Corporates (PBCs) and native title organisations clearly outline in their rulebooks how they will deal with disputes over membership. It’s important that you keep up to date with changes to legislation.

ORIC has a video and information on Resolving problems for incorporated organisations that you may find useful when resolving conflicts, disputes and complaints.

Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation has clearly documented processes for dealing with complaints, grievances and appeals.2Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Voices of Our Success: Sharing the Stories and Analysis from the 2014 Indigenous Governance Awards (Sydney, 2016), 89.

Making a complaint

Clients may send a written statement of their grievance to the organisation or the CEO. The grievance or appeal may also be made in person or by phone. The client may also give another person permission to help them make the complaint. For example, by interpreting or helping them to speak up strong. Staff must support a client with their complaint by then recording it in writing – even when the complaint is against staff.

Recording the complaint

A relevant senior Waltja worker will follow up the grievance at the earliest opportunity and record all action taken on a grievance/appeal form. This needs to be done whether or not the grievance has already been resolved to the client’s satisfaction.

The CEO may also require the staff members concerned to complete a grievance/appeal staff report.

Dealing with the complaint

If clients or community representatives have a grievance about any aspect of Waltja’s training or client services, they are encouraged to discuss the grievance with the responsible staff member.

This staff member will attempt to resolve the grievance through discussion and mediation with the people involved, or through making changes to their own practice. They must let the complainant know what steps are being taken to address the complaint. If the client prefers not to deal directly with the relevant staff member, they are encouraged to go to the CEO.

Unresolved complaints

If a grievance remains unresolved, the CEO will refer the grievance to Waltja’s executive. The executive will consider the grievance and provide an opportunity for the person to present their case. The decision of the executive will be final. Waltja will then give written advice to the client about the decision.

Lodging appeals

Clients may wish to lodge an appeal against a Waltja decision which affects them. When an appeal is lodged, the CEO identifies an independent panel of two people. These individuals have the cultural and language skills needed for liaison with the client who lodged the appeal.

The client must be given the opportunity to formally present their case. The panel will advise Waltja and the client of the outcome of the appeal (via a grievance/appeal panel report). Waltja then follows up with written advice to the client about the panel decision.

Peacemaking policies, procedures and rules

It’s helpful if your peacemaking processes are formally established and written down. One way to do this is to develop specific peacemaking policies, procedures and rules.

Today, instead of adopting off-the-shelf rules created by others, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are developing their own customised policy manuals and codes of conduct to suit their specific needs and operating environments.

Peacemaking policies are the high-level guidelines that lay out how conflicts, disputes and complaints should be managed by your group. Broad governance policies should set out the codes of conduct, roles, responsibilities and rights of the board, management and staff in relation to members — and vice versa. Policies should also outline a multi-stage process with a set timeframe for resolution. Policies could include:

- Client feedback and complaints policy

- Access to services policy

- Complaints and appeals policy

- Procedure for external stakeholders.

Policy documents often include rules. Rules provide concrete instructions on how to manage conflicts within your group.

Peacemaking procedures are the specific steps or actions that you need to take to implement these policies.

Not all peacemaking policies and procedures are the same. You should consider the types of conflicts, disputes and complaints your group manages. For example, the way you resolve external conflicts is likely to be different to the way you resolve conflicts between members.

Importance of policies, procedures and rules

Having formal policies, procedures or rules can help your group establish a framework for successful peacemaking. Advantages include:

Consistency

Consistency is key to successful peacemaking. It ensures everyone involved is treated fairly and equitably.3 Matthew Burr, “Conflict Management and Dispute Resolution,” SHRM, May 2021, [link] Don’t base decisions on family connections or a single leader’s opinion. Clear and consistent policies, procedures and rules can prevent misunderstanding. It also makes sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to present their perspectives and concerns. Keep in mind that things do not always have to be done exactly as they were done in the past. Governance is always evolving.

Time management

Peacemaking policies, procedures and rules help you manage conflicts as quickly as possible. They can outline specific timeframes and deadlines for each stage of the process. This can strengthen efficiency and minimise the likelihood of the conflict, dispute or complaint escalating.

Compliance

Formal policies, procedures and rules can help your group meet your obligations and comply with laws.

Prevention processes

While having policies, procedures, and rules to deal with conflicts is essential, groups can also take action to lower the chances of issues happening in the first place. The purpose of prevention is to address conflicts before they escalate, rather than simply reacting to them once they occur. Doing so can lead to more stable and peaceful environments where conflicts are less likely to occur.

“Koobara believes that the best way to reduce complaints is to put in place measures to prevent or restrict the possibility of conflict occurring. Koobara does this by displaying strong leadership; developing policies and processes; effective and strategic management and having skilled and motivated staff.”

– Koobara Aboriginal and Islander Family Resource Centre, Incorporated Category A Shortlisted Applicant

Below are several areas and considerations groups should focus on when designing prevention processes:

Build a strong internal culture

Having a strong internal culture is key to preventing conflict. When everyone is treated fairly and respects one another, people feel more comfortable expressing their issues or concerns in a respectful manner – before they become bigger problems. To learn more about building strong internal cultures, see Recognise your internal culture.

Seek feedback

Conflict can arise when a group’s members, stakeholders or wider community don’t feel heard. By seeking and listening to feedback, leaders demonstrate that they respect the viewpoints of others and can prevent conflict from arising. Feedback is a valuable tool for communication. It gives people the opportunity to share their ideas and concerns respectfully. For more information on seeking feedback, see Communication.

Follow through on decisions

Conflict is unlikely to arise when decisions are acted on as soon as possible. This is especially important when feedback is received. Following through on decisions makes it possible for leaders to address issues early – before they become more serious and potentially grow into conflict. By doing this, leaders demonstrate they are proactive and committed to making positive change.

Know the signs

To help prevent conflict, your group should monitor your governance regularly. This means checking for and identifying signs of confusion, misunderstanding or tension. It’s important that your leaders educate themselves about the common causes of conflict. This makes it possible for them to better recognise conflict before it becomes more serious. Learn more about the common causes of conflict in Understanding conflicts, disputes and complaints.

Provide training and education

Offering training and education is important to make sure members and leaders learn how to prevent and navigate conflict. These initiatives can help improve an individual’s listening and communication skills, understand the common causes of conflict, and learn how to overcome them. This training can help your group proactively address and resolve conflict before it escalates.

The Tiwi Youth Diversion and Development Unit (TYDDU) is a service based in Nguiu, Tiwi Islands. Originally beginning as a juvenile diversion program, TYDDU has expanded to offer a wide range of initiatives aimed at responding to family and community disputes. The service is locally run and prioritises respect for cultural values, rules and protocols.

Members of the Tiwi community have recognised the importance of the training and education programs to prevent conflict from arising. The type of education sessions suggested include:

- budgeting

- housekeeping

- parenting skills

- dealing with emotions

- anger management

- communication skills

- conflict-resolution skills.

The goal of these initiatives is to equip individuals with tools to navigate challenges and strengthen relationships to ensure the safety and peacefulness of their community.2Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009), 72.

Types of peacemaking

Both formal and informal peacemaking has been tried and tested by organisations involved in the Indigenous Governance Awards to resolve conflict or disputes.4Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards, (Canberra: Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2018, Prepared by A. Wighton), 77-79.

Informal peacemaking

Informal peacemaking involves supporting employees and senior staff to resolve conflicts among themselves. For this to work, encourage clear, honest and respectful communication, and provide a culturally safe and secure working environment.

Your organisation can also focus on role modelling at board, management and staff levels. This means the board and CEO demonstrate strong leadership and effective and strategic management.

Other informal processes include seeking client, stakeholder and broader community feedback regularly through surveys, workshops, forums and community meetings. It’s important to take any feedback on board, and implement changes, if needed.

It is good practice to try and resolve conflicts informally. If informal methods are not able to resolve the conflict, then you can move onto more formal procedures.

“A workplace that is physically and emotionally safe is conducive to productive, harmonious work relations.”

– ‘Maps to Success. Successful Strategies for Indigenous Organisations’, AIATSIS 2007

Formal peacemaking

Formal peacemaking includes written complaints and dispute resolution policies and procedures. These include multi-stage processes with clear timeframes for resolution. For example, some organisations have warnings as a first step in resolving internal conflicts and disputes.

Formal peacemaking can involve arranging facilitated discussions between parties, such as counselling and/or informal mediation.

Formal peacemaking may also include involving Elders councils and advisory boards, or appointing professional mediators or external consultants to investigate the conflict.

Your CEO may provide summaries of conflicts to the board. It’s also important that staff have training that focuses on procedural and legislative requirements and best practices.

Legal intervention should be a last resort.

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) is a peacemaking process that avoids litigation. This means it doesn’t involve going to court to resolve the dispute. ADR:

- helps parties to talk through the issue cooperatively

- encourages active listening

- designs solutions that are realistic and acceptable to everyone involved.5Helen Bishop, Aboriginal Decision making, problem Solving and Alternative Dispute Resolution – Challenging the Status Quo, in: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indigenous Communities (ADRIC) Symposium, 27 July 2015, Melbourne.

Depending on the context, the ‘alternative’ process may be:

- arbitration

- negotiation

- conciliation

- facilitation and mediation, or

- another means of resolving the dispute.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been practising forms of ADR for thousands of years. For example, Elder arbitration, agreement-making and various forms of consensus building.6 Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander processes of ADR are often focused on restoring and repairing relationships in a way that is mutually accepted and customised to suit their needs.

Arbitration is a formal process where a neutral third party (arbitrator) reviews an issue and makes a binding decision to resolve it outside of the court system. Constitutions and rulebooks may require arbitration if mediation fails.

Conciliation is where a neutral third party facilitates a dialogue between conflicting parties to promote understanding.

Negotiation occurs when parties engage in direct discussions to reach a mutually acceptable agreement.

Mediation usually deals with parties in conflict with each other. It involves negotiation and compromise to reach an agreement. A ‘mediator’ helps the parties involved with this process. Depending on the nature of the dispute, it may be useful to engage an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander psychologist as a mediator. Particularly if there is trauma or heavy emotions involved.

A mediator’s job usually focuses on assisting parties to resolve their differences.

Facilitation is usually centred around working through strategic problems – such as agreeing on the group’s direction or collective goals. A ‘facilitator’ helps to make sure all the relevant information or perspectives are considered and discussed.

A facilitator’s role is to help a group come to a joint decision. Depending on the situation, aspects of both facilitation and mediation may be helpful.

Some groups use the term peacemaker to define mediators or facilitators. Peacemakers are neutral individuals – often respected Elders – who are selected and agreed upon by everyone involved.7Helen Bishop, Aboriginal Decision making, problem Solving and Alternative Dispute Resolution – Challenging the Status Quo, in: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indigenous Communities (ADRIC) Symposium, 27 July 2015, Melbourne.

An ADR peacemaker can assist by helping people:

- hear and understand the other’s point of view

- identify and isolate the cause of the conflict, dispute or complaint

- develop and explore resolutions and consider alternatives

- support those involved to reach an agreement that accommodates their needs and interests.8“Alternative Dispute Resolution,” NT Law Handbook, accessed June 2023, [link]

Different states offer different support in finding and selecting a peacemaker. In Western Australia, the Aboriginal Mediation Service assigns a qualified mediator to resolve conflict in a culturally sensitive manner. In NSW, Community Justice Centres (CJC) provide Aboriginal mediators to help manage conflict within communities.

In the 1990s in Halls Creek – a small town in the East Kimberley, Western Australia – a feud between the women in two Aboriginal families was resolved through a process of co-mediation.

The mediation involved a panel of three co-mediators – two Indigenous men and one Indigenous woman. They were supported by the Western Australian Police, the Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS), the East Kimberley Aboriginal Justice Council (AJC) and the local Magistrate.

As well as restoring peace, the co-mediation process resulted in criminal charges being withdrawn against the families. Several people involved in the dispute – including an Aboriginal Police Liaison Officer and an ALS Field Officer – agreed to set up a mediation process with the families. The panel was carefully selected to make to include a mix of gender, skills and experience. The mediators were from the East Kimberley region, were held in high esteem by their communities, and had local knowledge of the families involved.

Over a period of two to three weeks, the families consented to the mediation process. They were reassured the process would be fair and everyone would have equal opportunity to have their say.

The mediation process was informal. There was no documentation or written agreements from either family. Discussions took place at a neutral location – the Halls Creek courthouse – rather than at one of the several Aboriginal organisations in Halls Creek.

The process began with separate meetings with family members – including the grandmothers, mothers and the girls.

Families had time after each meeting to discuss matters among themselves. This also gave mediators a chance to assess progress and to review their strategy.

The mediation concluded with a discussion between all family members and mediators. The families confirmed that peace had been made.2Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009).

Culturally legitimate peacemaking

For your peacemaking to be effective, it must be culturally legitimate. This means it must align with the cultural values, traditions and practices of those involved. Peacemaking has been part of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies since long before colonisation. These traditions and protocols are deeply embedded in culture and aim to make remorse, forgiveness and healing possible.9Helen Bishop, Aboriginal Decision making, problem Solving and Alternative Dispute Resolution – Challenging the Status Quo, in: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indigenous Communities (ADRIC) Symposium, 27 July 2015, Melbourne, 5.

Culturally legitimate peacemaking is about customising your processes to local needs, beliefs and values. They must be accepted by the group, individual or organisation. This might mean involving all the right people in the process. It might mean holding the meetings in the right places. It might mean those involved endorsing the facilitator or mediator.

Culturally legitimate peacemaking does not replace existing traditional dispute mechanisms. Rather, it recognises and incorporates the cultural values and protocols of those involved – including:

- kinship protocols

- respect for traditional owners

- ceremony

- approaches to gender.

By respecting and upholding these practices, your group is more likely to have a positive long-term impact when addressing conflicts, disputes and complaints.

Another key element is making sure everyone involved has a high level of control and self-determination throughout.10Loretta Kelly, “Mediation in Aboriginal Communities: Familiar Dilemmas, Fresh Developments,” Indigenous Law Bulletin 5, no. 14 (2002), [link]

It is important that groups consider ‘two-way’ governance when peacemaking. The aim of two-way governance is to develop governance arrangements that achieve a workable balance between cultural legitimacy and maximising self-determination with following any rules and regulations of wider society.

Women from Ali Curung in the Northern Territory developed a series of paintings which they used to explain to other communities how family violence and community law and justice issues are dealt with at Ali-Curung. One painting was called Two Ways: Yapa and Kardiya Ways. It depicts the Aboriginal dispute-resolution process at Ali Curung in the Northern Territory.

The Kurduju Committee explain:

“The left side of the painting represents the Yapa [Aboriginal] dispute resolution process. Community organisations are represented by three circles arching over the one larger centre circle, representing a community meeting. The two bottom circles represent Elders and Traditional Owners. These two groups act as adjudicators and provide legitimacy to the decision-making processes. The right side of the painting describes the Kardia [non-Aboriginal] criminal justice process. The painting depicts a Judge, the Secretary, Jury, Prosecutor, Defence Lawyer, the troublemaker and members of the public.”

-Kurduju Committee, 2001.2Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009), 85.

Steps for culturally legitimate peacemaking

The following steps will help guide you through culturally legitimate peacemaking. You can use the conflict analysis tool at the end of the topic to develop your own process.

1. Understand the conflict

Explore the nature and scope of the conflict. Think specifically about what is behind it and consider the different factors that may be contributing to the conflict. These may be internal or external, or a combination of both.

It is important to find the ‘root’ cause of the conflict. The root is the main reason or source of a conflict. Sometimes, the root cause may not be clear. In these situations, it is helpful to think about the conflict’s context.

Context refers to the surrounding factors, events, and circumstances that influence a conflict. Understanding context can help uncover underlying reasons and dynamics that shape a conflict. For example, there may be deeper, structural causes behind an issue.

Structural causes are things beyond the control of an individual or community. For instance, a structural cause behind unemployment might be that there are limited jobs where you live. When there is one good job going, this might encourage competition, or even jealousy, for those who want the position.

Cultural differences, limited access to resources, and lack of access to health care can all be structural issues that may contribute to conflict.

Encourage everyone to respectfully express their concerns, perspectives and needs. Listen to those of others. Summarise the discussion until there is consensus on points of agreement and disagreement.

2. Identify those involved

Identify the people directly involved in the conflict. These groups and individuals are known as the ‘parties’ to the conflict. Next, identify those who will participate in the peacemaking process. This may include not only the parties to the conflict, but also those who have witnessed or been affected by it.

Keep in mind that it may not be possible or suitable for all parties to participate in the peacemaking process. For example, it may be more appropriate for a family member to represent a group. This might be appropriate if there are multiple individuals involved in the conflict, if some people are unwilling to participate in peacemaking or if it is difficult to get everyone together at the same time or place. Make sure there are an equal number of representatives from all parties.

3. Choose your peacemaking process

Consider what process or approach will suit the situation and those involved best.

In choosing your peacemaking process, you might need to consider whether there is a need for a neutral third party like a psychologist, a mediator or a facilitator.

When arranging mediation with a third party involved, it is important to give thought to the following types of considerations:

- Consider whether the third party should be part of the community or an ‘outsider’. An outsider may be appropriate when there are concerns around confidentiality or fairness, or when a particular skillset is required.

- Consider whether both male and female co-third parties are needed.

- There may also be language differences to consider, so a translator might also be needed.

- If a third party is required, it’s important they are respected by everyone and have knowledge of their local protocols – such as an Elder. Solutions presented by Elders are less likely to be rejected by the parties involved and more likely to be seen as legitimate. Their role is to encourage respectful dialogue and provide guidance based on knowledge of culture, traditions, and law.

- Ensure that agreement has been obtained from all participants regarding the third party, if necessary. In some cases, third parties are not chosen by participants themselves. For example, if the conflict has been referred to a community mediation centre, such as a community justice centre (CJC), then the CJC may provide the mediator.

- You may need to take a ‘shuttle mediation’ approach, where a mediator moves between parties so that a dispute may be resolved without the parties coming face to face.

Remember that mediation with a third party isn’t the only peacemaking process you can follow. It may be more appropriate to have parties engage in a yarning circle or a whole-of-community meeting.11 Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009).

Make sure the process you choose does not further exacerbate a conflict, entrench people into opposing positions, or wrongly exclude people. For each step in your process, you can ask:

- What is the purpose of this step?

- Is it likely to have a positive or a negative impact on those involved?

4. Choose the right time and location for peacemaking

Once you understand the wider context of the issue, bring everyone together in a culturally safe and neutral space.

Consider whether it’s important for dispute resolution to take place in person, rather than online. Think about where it should take place – on Country, in a private or public space, inside or outside, in a formal or informal setting.

If online, consider whether peacemaking should take place in ‘real-time’, with all parties present for the process. Direct, ‘real-time’ communication will likely require a third party to be brought into the process.12 Michael Legg, “The Future of Dispute Resolution: Online ADR and Online Courts,” forthcoming Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal, 2016, [link] It may be more practical to have individuals communicate via email or other messaging platform.

5. Plan your timeline

Some disputes may be resolved relatively quickly, while others may need a longer timeframe.

For example, you may require multiple meetings. It may be necessary to allow time for mediators to establish trust, and for people to discuss options with family. Spend enough time to take all parties’ views into account, as well as the history and relationships involved. This could include allowing time to ‘take a step back’ and talk about the bigger picture. For example, inviting parties to explain the lead-up story to the conflict or dispute from their perspective.

Make sure enough time is spent explaining the peacemaking process, who will be involved and any possible outcomes. Give people free and informed consent to processes and agreement outcomes. This might include:

- taking the time to go through any written documents step by step

- allowing time for discussion

- inviting questions.

Check in with all parties throughout the process to make sure they are following and understanding what’s going on.

Peacemaking that is more flexible around timeframes is often better able to respond to the needs of parties. Open-ended peacemaking gives time to deal with changes in circumstances or underlying disputes that may arise.

There may be additional time required depending on the mobility of clients, whether extended family members need to be included, and the geographical distances which may need to be covered by all those involved.

6. Discuss the best outcomes

Encourage everyone to come up with possible solutions to the conflict, dispute or complaint. Consider the short-term and long-term implications of each option and think about how viable they are. The goal is to satisfy everyone’s interests as best as you can. Make sure you refer to your group’s policies or procedures where possible to help you make the decision.

When discussing outcomes, it’s good practice to take a consensus approach to decision-making. This means not rushing decisions and not imposing ‘quick fix’ solutions at the expense of sustainable resolutions. Consensus might look like coming up with a solution everyone involved feels okay with. A sustainable solution might be one that is going to help resolve or manage the conflict today, as well as down the track.

Make it possible for people to take part in and own decisions and solutions. This might look like giving all parties a say in the process, who is involved, and what outcome you are working towards. Having ownership over these aspects is key to feeling empowered to change the situation for the better.

The best outcomes will promote social satisfaction and restoration of harmony among the parties involved. This might include thinking about – and asking all parties – what has to happen for peace to return. This might include compensation, a court sentence, a truce, or other deal being agreed to.

Conflicts are often complex and may not be straightforward to fix. If you cannot agree on a solution, you may have to consider alternative approaches. Let individuals and groups withdraw if that seems like the only option. If an agreement cannot be reached, your group may have formal guidelines to follow.

7. Follow up

It is useful to evaluate how well the dispute resolution process went. Invite the involved parties to provide feedback on whether they were satisfied with the process and the mediators, facilitators, or peacemaking practitioners involved.

It’s also important to follow up with the parties after the process has taken place to ensure the peacemaking has been sustained. Follow up can be formal or informal. At the Tiwi Youth Diversion and Development Unit (TYDDU), for example, follow up takes place informally. Staff members check in with those involved in the peacemaking process. If they believe the issue has not been resolved, they bring the matter to the attention of senior staff, who decide whether further assistance is necessary. Community networks also check up on people who have participated in the peacemaking and to inform referring agencies of the outcomes. 13Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009), 63.

This tool will help you understand why a conflict is happening, consider the different perspectives and people involved, and then develop a peacemaking process to address it.

Consider each of the questions and use the prompts to help you answer them. You can add your answers in the space provided, or use butcher’s paper, sticky notes, or a whiteboard. Remember, there may be more than one perspective/explanation for each of these questions. It will be useful to read through the above steps for culturally legitimate peacemaking before you work through the tool.

Community-controlled peacemaking

Around the world, First Nations communities are maintaining or re-establishing their own internal processes for peacemaking.

Community-owned and run peacemaking is beneficial because it rebuilds and repairs Indigenous forms of authority and social order. It does this through place-based, community-controlled leadership and decision-making. Strategies that improve the way people relate to one another and show community members that their voices are heard help to strengthen overall community governance.

Community-controlled processes ‘break the cycle’. They do this by addressing conflicts in a manner that is free from government interference. This conflict is often deeply intertwined with trauma stemming from the damage caused by decades of settler-colonialism.14Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021).

Community-led peacemaking demonstrates that your community values effective governance and recognises the importance of ensuring your community is strong, accountable and committed to continuous learning and improvement. It allows community members to feel safe when seeking assistance with resolving conflict. It also provides an alternative to expensive external processes – such as the court system.

It’s important that community-led peacemaking incorporates community leaders or respected Elders who have knowledge and authority to assist with managing conflict. Recognise and build on local capacity, knowledge and skills. This might include employing a local mediator that is agreed by parties to be a good fit, or drawing on local concepts and processes – such as Makarrata or truth-telling.

Community peacemaking should aim to resolve conflict as close to the source as possible. This helps makes sure both sides are satisfied with the outcome. It is also faster and less disruptive than external legal proceedings.

When you control your own peacemaking processes, you can incorporate your unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages and institutions to suit your community.15Canadian Human Rights Commission, A Toolkit for Developing Community-based Dispute Resolution Processes in First Nations Communities (Canadian Human Rights Commission: Ottawa, 2013), 6-9, [link]

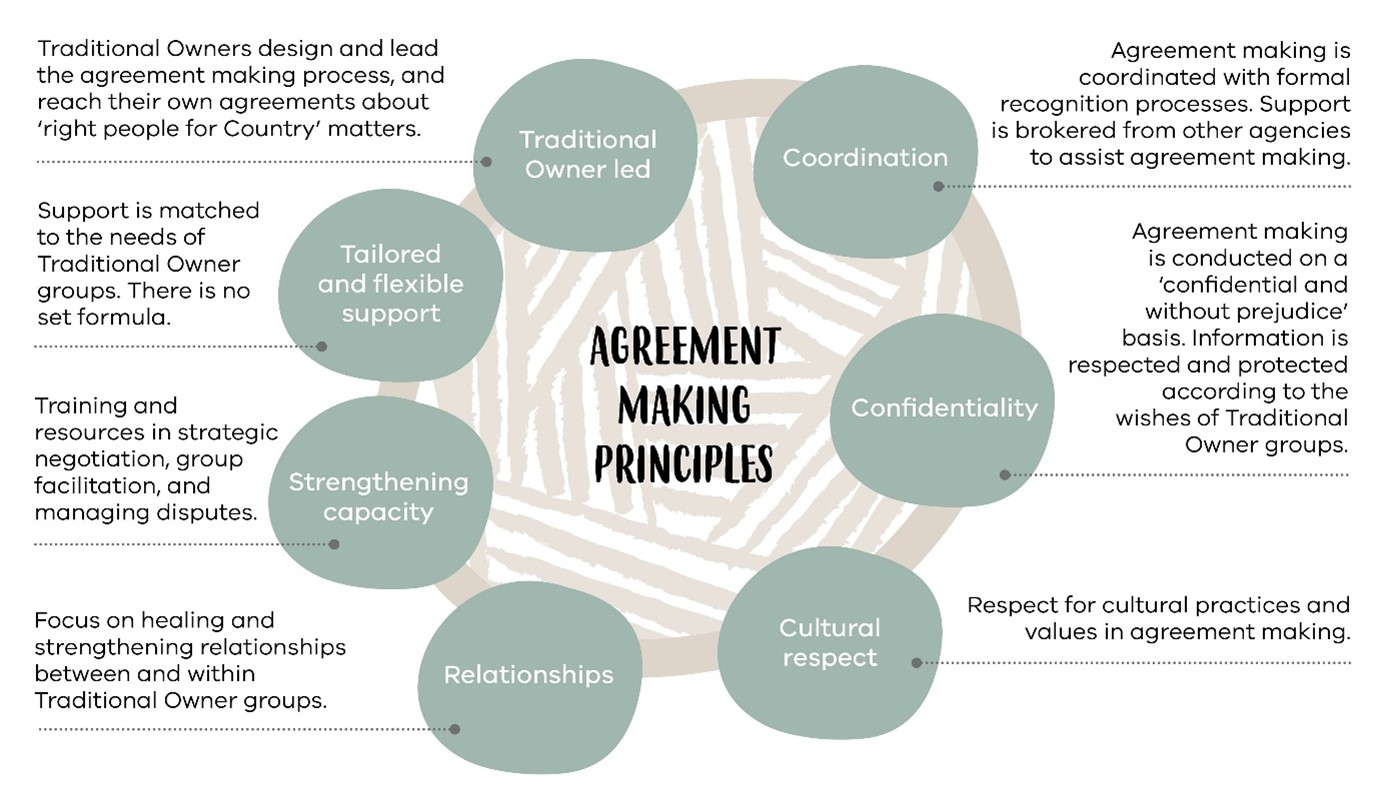

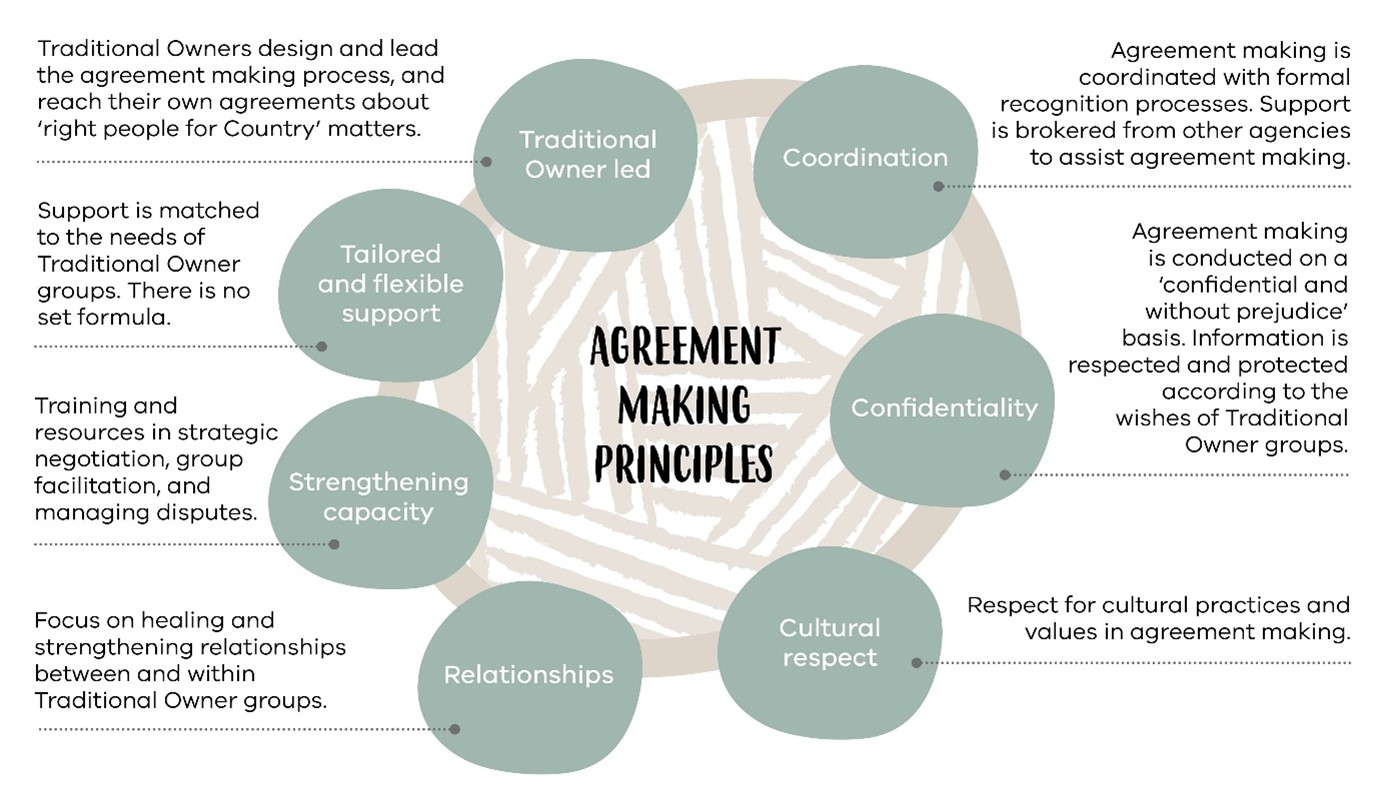

The Right People for Country program is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led project that supports traditional owner groups in dispute resolution and agreement-making. It supports groups in making decisions:

- between groups – about boundaries and extent of Country

- within groups– about group representation and membership.

The program supports traditional owner groups in reaching agreements about Country and traditional owner identity themselves, rather than having governments and courts make the decisions.

Support is tailored to each group and includes:

- independent facilitators

- training (strategic negotiation, group facilitation and dispute resolution)

- planning workshops

- support to visit and map country

- resources to hold meetings.

The Right People for Country program follows a 5-step agreement-making process. It has also established a set of principles for traditional owner-led agreement-making.

Developing a community-controlled peacemaking process

Community peacemaking is about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and nations working through conflict and healing trauma. The Canadian Human Rights Commission refer to this as community-based dispute resolution. They highlight four key ‘ingredients’ to successfully developing a community-based dispute resolution process.16Canadian Human Rights Commission, A Toolkit for Developing Community-based Dispute Resolution Processes in First Nations Communities (Canadian Human Rights Commission: Ottawa, 2013), 11, [link]

These are:

- Leadership, values and principles.

- Capacity building for development and engaging your community.

- Developing your community’s dispute resolution model.

- Implementation, monitoring and continuous improvement.

When developing your community’s own peacemaking process, there are a number of key aspects to consider.

Do this activity to develop a peacemaking process for your community or nation. Consider each of the key aspects and use the prompts to help you think through the various elements of a dispute resolution model. Add your own reflections next to each.

The Muntjiltjarra Wurrgumu Group (MWG) was awarded Highly Commended Category B in the 2014 Indigenous Governance Awards.2Category B recognises non-incorporated Indigenous projects and initiatives. In this video, MWG members Regina Ashwin and Stacey Petterson discuss how the family groups put their differences aside to work together for the whole community.

Peacemaking in different contexts

Different conflict situations may require distinct peacemaking processes. The following strategies outline common methods that organisations can use to address conflicts, disputes, or complaints in different contexts.

Your board directors need to be able to work together well so they can set the organisation’s direction and govern effectively.

While it’s not unusual for conflicts or disputes to happen in a board, it’s important they are resolved so the board can continue to make good decisions.

Effective strategies to build the capacity of your board to deal with conflict include:

- Delivering customised training in dispute mediation and negotiation

- Making sure the board annually self-evaluate its governance performance, and its ability to work and make decisions as a group

- Providing regular briefings and progress reports on issues under dispute

- Developing specific policies setting out expectations for codes of conduct, conflicts of interest, governing roles and responsibilities, and guidelines for resolving internal disputes and complaints

- Delivering training in how to run productive meetings and make consensus decisions

- Developing protocols and procedures for grievances and appeals

- Using the strategic plan, succession planning and future vision as guides for more consistent decision-making, and to reduce factionalism and conflict

- Drawing on the cultural input and advice of the wider peer groups of leaders in a community or nation

- Developing governance charters and manuals setting out agreed values, rules and commitments.

The relationship between the CEO and board needs to be a working partnership. It’s important to make sure that any signs of discord or dispute are managed early.

The chair and CEO need to be able to work well together to maintain harmony at board and organisational level.

It’s important for the CEO to support the chair in mediation and encourage the board to follow its own code of conduct.

One of the most important duties of a board is to hire, supervise, evaluate – and if needed – dismiss the CEO. This job can be undermined if there is tension and conflict between directors and the CEO.

Effective strategies for dealing with conflict between the CEO and the board include:

- Honest and informative communication and feedback between a board and CEO

- Clearly setting out, understanding and having mutual respect for each other’s roles, knowledge and responsibilities

- A clearly enforced chain of command between the board, CEO, managers and staff

- Regular meetings between the chairperson and CEO to discuss potentially problematic issues

- Expectations and standards for the CEO’s conduct, set out in their contract and performance agreement

- Annual review of the CEO’s performance, carried out by the board

- A written code of conduct – this may be specifically for the CEO, or part of the broader code document for all management and staff

- Written procedures for counselling and/or dismissing the CEO for poor performance, misconduct or prolonged dispute with the board

- Written procedures for appeal by the CEO for unfair dismissal or treatment by the board

- Written policies and delegations to enable the CEO to get on with their job without hostility or interference from the board

- Professional development, mentoring and training opportunities for the CEO in mediation and negotiation skills

- Succession planning for the CEO’s position – no one stays forever.

The best atmosphere for staff members is one of collaboration, mutual respect and stable leadership. The staff of many successful Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations have described it as ‘being like a family’.

It’s best if internal conflict, disputes and complaints are resolved by the next level in the chain of command.

If this is not successful, the CEO should make the final decision, or decide on the best process to follow – for example, mediation.

Some organisations expect their governing body – specifically the chairperson – to be involved when there’s conflict between management and staff. Others specifically restrict this from happening. Many organisations develop processes to ask leaders or Elders from the wider community for advice and intervention.

Whatever your approach, it needs to be clearly documented, communicated and understood by staff.

Staff dissatisfaction and poor work performance can easily erupt into conflicts. However, they can be effectively prevented using these strategies:

-

- Have detailed HR policies and written procedures that clearly set out the rights, roles and responsibilities of management and staff, including how disputes and complaints should be addressed at staff meetings

- Develop staff codes of conduct

- Ensure expectations and standards for staff conduct are set out in their contracts and performance agreements

- Develop clear rules and procedures for the working relationship between staff members and the board

- Have a clear chain of command and lines of reporting, supervision and delegation

- Ensure consistency and fairness in decision-making and policy implementation by managers

- Hold annual performance reviews where a range of sensitive issues can be discussed and addressed

- Provide professional development and career opportunities.

Provide cross-cultural training, inductions and customised training that deal with processes for resolving conflicts, disputes and complaints. Give staff access to external mediation or counsel if disputes are entrenched or focus on the CEO.

Encourage a strong internal culture that values feedback and open communication across the whole organisation.

Marninwarntikura Fitzroy Women’s Resource Centre (MWRC) aims to create a positive, safe and supportive work environment to assist staff to deal with trauma and minimise the risk of internal disputes.2Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards, (Canberra: Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2018, Prepared by A. Wighton), 78. MWRC describe their dispute minimisation strategy:

“With the growth of the organisation, MWRC has developed a series of policies and procedures … part of the healing approach that the organisation has adopted is to ensure that all staff feel safe and are in a caring environment and that they are free to express their concerns and worries.”

Part of their approach to dispute resolution involves a specific position for a Workforce Development Manager. According to MWRC, this process has:

“Allowed grievances to come to the surface quickly and be solved by offering staff non-monetary benefits such as time away from a higher trauma environment, flexible working hours, additional long weekends throughout the year, on Country experiences etc.”

Use this check-up to see what you are doing well to manage conflicts in your organisation and get ideas for how you could improve your processes.

This should not replace a thorough evaluation of your processes. It is a good starting point to give you an overall picture.

Its main purpose is to help you:

- identify problems or gaps in your policies and procedures

- identify your internal strengths

- start discussions and get people involved

- work out which areas need closer evaluation and possible change

- identify priorities.

These check-ups are intended for self-directed assessment. They can be used by leaders, board directors, or group members who want to evaluate the governance and leadership of their organisation, community or nation. You can do the check-up on your own or as a group and then compare results.

Peacemaking with external parties

Conflicts, disputes and complaints can also happen with external parties, for example, with your broader community and stakeholders. These could be clients, funders, program participants or partners.

If your organisation has written policies or procedures on how to deal with complaints from external parties, these should be followed. In some industries, for example health services, there may be additional obligations or requirements you must comply with in setting processes to deal with external conflicts, disputes, and complaints.

It’s important to respond to complaints from your broader community and stakeholders with care. People name communication, fairness and cross-cultural sensitivity as critical factors in doing this.

Strategies for external peacemaking used by applicants in the Indigenous Governance Awards include:

- Supporting senior staff to resolve complaints with stakeholders directly themselves

- Taking on board feedback from clients during and after programs, and implementing changes as a result

- Seeking client, stakeholder and broader community feedback regularly through surveys, workshops, forums and community meetings.17Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards, (Canberra: Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2018, Prepared by A. Wighton), 79.

Peacemaking within incorporated organisations

Organisations incorporated under Australian law must meet particular governance conditions, or standards. These include following rules and procedures to manage circumstances that meet the legal definitions of a dispute or complaint.

Generally, regulators – such as ORIC – do not get involved in internal disputes in incorporated organisations. They may use audits to investigate and ensure compliance with the law. Any actions believed to be against the law can result in an organisation being placed under administration and/or prosecution. This may result in fines and/or jail time.

In some instances, conflict or disputes may need to be reviewed by an administrative tribunal. Going to court should be a last resort. It is often stressful, time consuming and expensive. Sometimes, a court may be reluctant to interfere and may instead refer parties to mediation. It’s important to seek legal advice first.18“Handling disputes and conflicts,” Justice Connect, updated 2022, [link]

It is possible for a member to make a complaint about a corporation to ORIC if:

- your concern is governance-related

- it has been raised with the corporation

- the corporation has given you an inadequate response.

More information on making a complaint can be found on the ORIC website.

Use this template to create your own complaints process.

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

View all resources about Conflict resolution and peacemaking

.png)