To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Nation building in practice

In this topic, we explore practical strategies for nation building. We help you identify where you are on the ladder of self-governance. We outline the IPOA model – a practical process that many successful groups have used in their journey. We also look at seven core principles of nation building. These principles can help guide effective governance for groups looking to pursue sustained, self-determined development.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- Where are you on the ladder of self-governance? What steps can you take to get to where you want to be?

- What are the 4 steps of the IPOA model, and why might this be a useful way to approach nation building?

- Are there any characteristics that successful nation building strategies share?

- What are the 7 core principles of nation building in Australia?

Get started on nation building

Nation building – or rebuilding – often requires new conversations about the role and strategic vision of your group’s governance and how to achieve this vision.

Initially, it may be about a small area of decision-making control and responsibility. Whatever the focus, your governance arrangements must result from informed decisions by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples involved.

Redesigning governance arrangements is a sovereign decision. It involves the group collectively deciding, for itself, how it wants to govern. It’s what self-determination in action is about.

To begin your nation-building journey, involve your group in conversations and hard decisions. Think about how you can:

- draw on your unique governance cultures and traditions

- work from a basis of respect for and protection of your cultural identities

- determine what makes up legitimacy for your nation – who can speak when, for whom, to whom and about what (this includes making sure the vulnerable within your nation are equally represented)

- determine what kind of leadership you need

- decide what effectiveness and capacity mean for your nation, and then design processes, rules and structures to put them in place

- provide members with a voice to take part in decision-making about governance priorities, aspirations and arrangements

- engage with the wider governance environment and your networks, and insist on your governance arrangements being respected in relationships with other parties.

There are proven strategies to help begin these conversations and start making some of these difficult decisions. The strategies below are a guide. Groups adopt many different strategies when governing for nation building. You may find some strategies to be more or less suitable for your own group.

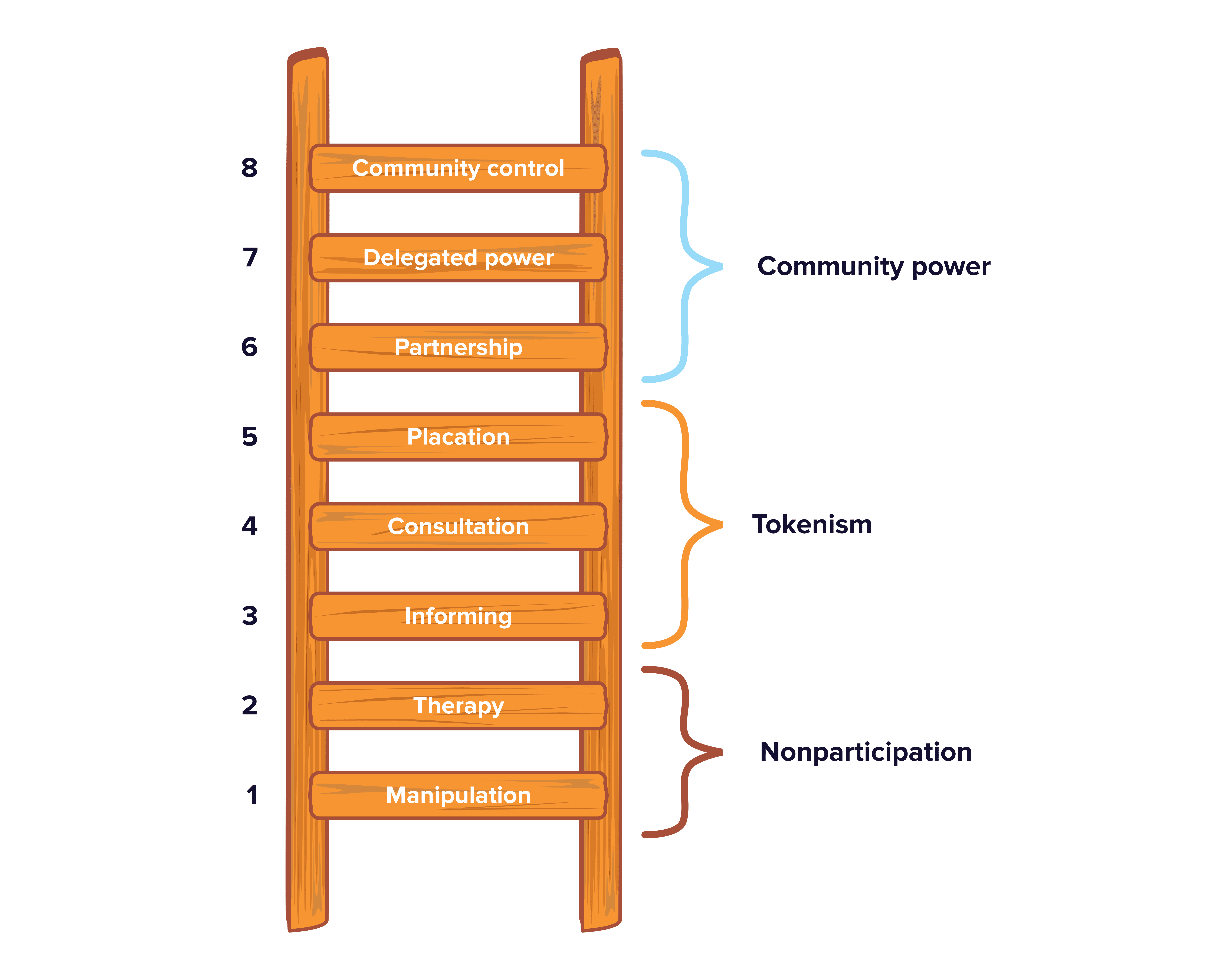

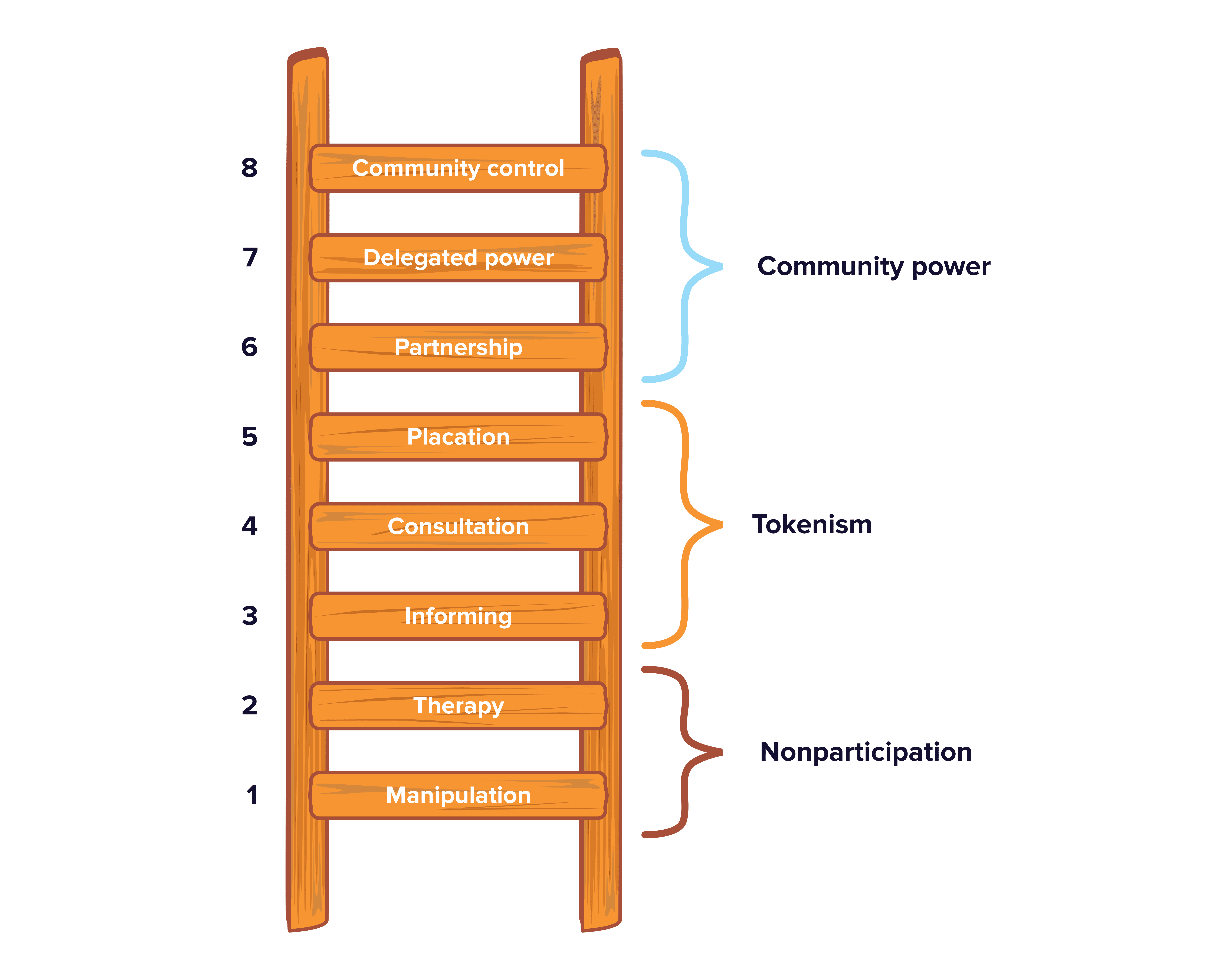

The ladder of self-governance

An important first step in governance for nation building is to identify where you’re at in your nation-building journey.

The ‘ladder of self-governance’ shows the levels for effective governance, decision-making authority and responsibility. In other words, it shows the steps towards self-determination for nation building.

The ladder of self-governance helps you understand:

- where your group is at in achieving self-determined goals

- how to start strengthening your capacity to govern.

Self-determination grows as decision-making power and responsibility moves from external authorities to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are transitioning from the pure ‘rights battle’ to the ‘governance and development (or implementation) challenge’. The practical capacity to govern is critical to future outcomes.

“The challenge for traditional owners, like the Yawuru, is how do we, as a people, leverage our native title rights so as to promote our own resilience and reliable prosperity in the modern world?”

– Patrick Dodson, Yawuru man, presentation, Common Roots, Common Futures: Different Paths to Self-determination—An international conversation, University of Arizona, 2012.

The process of nation building looks different for each group. It depends on their priorities and the approaches they take to reach the top of the ladder. In real life, there are many more rungs and complications. The move to a nation-building approach is usually a slow, stop-start process.

This tool will help you decide where your group is on the ladder of self-governance. As you look at the ladder, think about what rung of the ladder you want to be. Make a list of the plans, processes or tools you need, or already have in place, to get you there.

– Adapted from Sherry Arnstein, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”.2Sherry Arnstein, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no.4 (July 1969): 216-224.

Delegated power and community control

The top rungs – delegated power and community control – indicate that a nation has genuine participation and control. First Nations peoples have the majority of decision-making power over the things that impact them. They’re fully in charge of managerial and policy decisions and can negotiate with external stakeholders on their own terms.

Partnership

Rung six is about a group gaining increasing control of decision-making and governance influence. As members of a group, First Nations peoples can enter partnerships that allow them to negotiate and engage with external power holders. This is the start of genuine governing authority. For these negotiations to be effective, First Nations people’s access to resources and expertise must be equal.

Placation

At Rung five, participation is tokenistic. This means First Nations groups may have the power to advise, but it’s often outsiders who keep the right to make decisions. In these situations, First Nations groups should focus on making sure they can take responsibility for their own decisions and actions.

Informing and consultation

Rungs three and four are also levels of tokenism where First Nations groups may be informed and have a voice. While these rungs represent the first steps towards genuine self-governance, it’s important that the flow of communication is not one-way. Groups must also take steps to make sure their views are heard by those in power.

Manipulation and therapy

These rungs describe a lack of self-governance, where groups may have little to no opportunity for genuine decision-making power or participation. First Nations groups should focus on developing their capacity to take part in their governance in a meaningful way.

Steps to build your nation’s governance

National and international evidence suggests that the steps below are critical to building effective self-governance for the work of nation building. Thinking about how your group can start implementing these suggestions can help you climb the ladder of self-governance.

The following steps are adapted from:

- governance research and writings of Dr Neil Sterritt

- Australian Indigenous Community Governance Research Project at The Australian National University

- research of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, Udall Centre, University of Arizona.

Consider an incremental approach

First Nations often have many competing demands they must juggle – from governments, partners and other external stakeholders, and their own people. Be realistic about your capacity, resources and size. Start by achieving success with one or two achievable priorities, and then build on that.

With continued success, community leaders can begin to tackle a broader range of issues at the same time. This approach requires long-term commitment.

Incremental government initiatives for nation building can take many forms. For example, the Gugu Badhun Nation has developed the Gugu Badhun Peoples Community Plan 2020–2025. This plan provides the Gugu Badhun Aboriginal Corporation’s (GBAC) board members and community with direction on how to achieve Gugu Badhun’s social, cultural, environmental and economic aspirations. GBAC is the Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) holding the native title rights and interests as the agent of the Gugu Badhun people.

The community plan identifies five nation building activities:

- Storytelling

- Structuring the Gugu Badhun Aboriginal Nation

- Economic development framework

- Website development

- Project reporting

Under each activity are projects or tasks which aim to progress the work of Gugu Badhun nation building. These include:

- developing a political constitution

- holding online workshops to facilitate the filming of community stories and interviews with Gugu Badhun elders

- developing a Gugu Badhun economic development framework that outlines the Gugu Badhun Nation principles and values.

These five activities and their tasks are incremental steps that contribute to Gugu Badhun’s overall nation building. Read more about the Gugu Badhun Nation Building Project.

You can find more examples of incremental approaches to governance in strategic sovereignty.

Engage with your community

Make sure your members are behind you – they give you the authority to build governance.

A critical factor for building effective governance for nation building is communication with your members. Leaders must include their members in the planning and implementation of new governance arrangements.

Effective implementation is directly related to the level of support and engagement from your nation members. They are more likely to have trust and confidence in your governance proposals for nation building if they fully participate in and are consulted about the process and options.

Leaders should (and are expected to) come back to members of their nation and discuss ideas, information and decisions with them. Getting your members engaged in nation building means keeping them informed from the start. Member engagement and communication should also be ongoing, even when you expect they might disagree with some ideas.

Read more about conducting effective consultations with your group’s members.

“From the outset, we were conscious that we needed to engage broadly and inclusively with Wiradjuri people at the local level. It was crucial to have the wisdom of our local elders shape a shared understanding of the importance of the nation-building approach and to work together to develop a shared vision, so that we could move forward with cultural integrity and legitimacy. This does not mean that we asked elders to do the work, but rather to provide leadership, advice, and direction allowing us to progress the rebuilding with their blessing and appropriately for local circumstances.”

– Donna Murray and Debra Evans, Culturally Centred, Community Lead: Wiradjuri Nation Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way, 2021.1Donna Murray and Debra Evans, “Culturally Centred, Community Led: Wiradjuri Nation Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 180-181.

Focus on credible leadership

Effective leadership for nation building requires thinking about collective governance, and how to go about achieving it. Transforming a nation’s conversations and actions in this direction often requires what the Native Nations Institute describes as ‘Public Spirited Leadership’.2“What Is Native Nation Building,” Native Nations Institute, accessed 2022, [link] They explain:

“In successful First Nations, there is typically a group of individuals who recognise the need for fundamental change in the way things are done and can bring the community along with them in building that future.”

Credible leaders work hard to involve and unite the entire nation. The interaction between ‘leaders’ and their nation members is very important in sustaining their credibility. In their nation-building or rebuilding work, the most credible leaders will:

- think about the kinds of strengths, assets, resources, talents, skills, experience and knowledge they can call upon from the members of their nation

- embrace cultural values and traditions when designing governing arrangements

- make sure those with decision-making authority are accountable to the nation or community they serve

- make decisions that benefit the nation as a whole

- emphasise shared leadership and active member participation.

Read more about effective leadership for governance.

“Yawuru people are engaged in the reconstruction of the social and cultural fabric of our society, following more than a century of marginalisation and disenfranchisement. To achieve this formidable goal, we need to build a cycle of success in which a key element is unity of purpose and confidence within the community. Leadership is key to our social and economic transformation. We must rebuild the foundations of cultural knowledge and respect and integrate that into Yawuru contemporary governance, while at the same time develop the agility and resilience necessary to leverage opportunities to secure the economic future of our people in the emerging economy. This calls for a particular kind of public-spirited leadership, one that puts mabu liyan and the well-being of our people ahead of self-interest.”

– Peter Yu, Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation.3Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 245.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should be aware that this video may contain images and voices of persons who have passed.

Donna Murray reflects on the role leaders play in the nation building process. For the Wiradjuri nation, empowering their nation builders helps drive positive change in the community and increases the nation’s capacity to interact with external governments in a self-determined way.2Honoring Nations, “Reflections on the Next Horizon Symposium | Donna Murray,” June 1, 2019, from the Next Horizon: A Symposium on the Future of Indigenous Nation Building, 3:50, [link]

Identify strategic priorities and concerns

You cannot do everything at once. The current generation may have particular needs that will change in the future. Some foundations need to be built now, and others can be built later.

Taking a strategic approach to nation building helps you keep your group’s goals in perspective. You can start by identifying the priorities you want to focus on. Consider what you are trying to accomplish or achieve. This might be:

- reviving language

- negotiating a treaty or settlement agreement

- increasing funding and resources

- opportunities for economic development in local communities

- developing a framework for decision-making.

Some First Nations are developing strategic plans. Others are doing strategic analysis to determine what they need to achieve to reach their collective future vision. This often involves coming up with answers to questions like: What circumstances do we have to deal with? What resources do we have to work with?

Read more about strategic planning.

Tsawwassen First Nation, located outside of Vancouver, British Columbia, developed a strategic plan to help guide them as they adopted self-governance and entered a new treaty relationship with Canada and British Columbia. Their plan outlines a series of goals, as well as effective strategies Tsawwassen can take to progress towards these goals. As Tsawwassen First Nation explains, their plan:

“… sets out our vision for the future and our long-term goals for the Nation. It also identifies the objectives we will pursue in the next five years to help make our goals a reality, and it commits us to developing measures we can use to know if we are successful.”2Tsawwassen First Nation, Tsawwassen First Nation Strategic Plan 2018 – 2023, 2, [link]

Build capable and legitimate systems and plans

Effective nation building occurs when groups work to achieve cultural legitimacy when developing their systems and plans. These are your laws, constitutions, regulations, rules, policies, and checks and balances used to implement your governance. Ensuring that your approach is considered legitimate by your members means taking time to focus on:

- the ways structures of governance are created

- how leaders are chosen

- the process of consensus decision-making

- how internal accountability is secured

- the ways governance capabilities and knowledge are supported.

Every group has its own cultural values and traditions. This means the group’s governing structures, policies and procedures must be customised to fit its contemporary culture. These may also evolve over time. For example, the Gunditjmara People of south-west Victoria designed governing structures that used deliberative democratic strategies to:

- fulfil their obligations to Country

- negotiate agreements with the Victorian government

- pursue their native title, cultural heritage and traditional owner aspirations.

These structures were created to be both effective and culturally legitimate. Over time, however, the process of decision-making used by Gunditjmara (decisions were made through a monthly committee meeting) no longer suited their evolving circumstances. They are in the process of revising their decision-making structures.4Alison Vivian, Miriam Jorgensen, Alexander Reilly, Mark McMillian, Cosima McRae and John McMinn, “Indigenous Self-Government in the Australian Federation,” Australian Indigenous Law Review 20, (2017): 217.

Read about developing strong systems and plans.

Look hard at cultural solutions

Culture is a source of innovation. Look at your enduring cultural values and the realistic role they can play in revitalising your governance and nation.

Leaders who embrace cultural integrity work hard to harness the strength and resilience of cultural roots in ways that are credible and workable in today’s world.

Governance for nation building is most effective when leaders actively work to make sure their governance arrangements embody and reinforce their group’s contemporary values, norms, laws, practices and conceptions of how authority should be organised and leadership exercised.

Read more about culture-smart governance.

Wiradjuri nation rebuilders Donna Murray and Debra Evans explain how their nation building journey has evolved to become more deeply connected to Wiradjuri language and culture:2Donna Murray and Debra Evans, “Culturally Centred, Community Led: Wiradjuri Nation Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 165-166.

“Our goal is big — we are aiming to rebuild vibrant communities that have an attitude to freedom and sovereignty that is deeply grounded in the sacredness of Wiradjuri language and culture.

We are choosing our own reality rather than being blown off course by outside governments, incrementally rebuilding sustainable and culturally legitimate governance processes. The Wiradjuri language and culture are the philosophical compass for this process of restoring and making healthy, eternal Wiradjuri belonging/identity.

Our thinking and our work is undertaken within two complementary frames — Indigenous nation building, and the Wiradjuri cultural frame or standpoint stated in the title of this chapter: Bagaraybang burrambin Wiradjuri-giyalang (‘to restore and make healthy, eternal, Wiradjuri-belonging and identity’.) … The thirty years of research from elsewhere has been critical in changing our approach to education and development. However, the real transformation began when the wider Indigenous nation-building work became centred in a Wiradjuri paradigm. This community strengthening work is, consequently, a reflection of the wise practices of numerous Wiradjuri elders and other community-spirited leaders who continue to work tirelessly to restore Wiradjuri language and culture as the foundational asset for rebuilding vibrant and culturally legitimate communities in Wiradjuri country.”

Build governance capability

Make sure the governance capability and confidence of your people are actively developed and continuously promoted.

Do this in parallel with implementing your other strategic goals and agreements. Don’t leave this until a crisis hits. It’s no use having authority unless you can implement and exercise it. Developing your governance capabilities should be a process that actively:

- strengthens Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander decision-making and control

- prioritises your group’s goals and collective identity

- enhances cultural legitimacy.

Governance capability development works best when it is:

- place-based

- oriented around your group’s goal

- based on self-assessed governance priorities

- in a relevant form and delivered in ways that are meaningful to local members

- sustained and reinforced over the longer-term.5Janet Hunt and Diane Smith, Building Indigenous Community Governance in Australia. Preliminary research findings, CAEPR Working Paper No 31, (Canberra: The Australian National University, 2006).

Read about building the capabilities of your members.

Monitor and review

Make sure you monitor and review your checks and balances. This will help make sure your governance solutions continue to work as you want them to.

Monitoring the progress you are making towards your group’s identified goals means you can better assess whether they are on track, or what adjustments may need to be made to support your nation building work.

Community-based and locally controlled monitoring by First Nations is itself an exercise of governance.

See Systems and plans for information on reviewing your policies, procedures or strategic plan.

The Wunambal Gaambera people have worked collaboratively with researchers to develop the Uunguu Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (UMEC). The aim of UMEC is the monitor and evaluate the Wunambal Gaambera’s Healthy Country Plan (HCP). Wunambal Gaambera people developed the HCP to help keep Country and culture healthy for future generations. As Wunambal Gaambera explain:

“Embedded in the plan, and part of the healthy Country work, was the commitment to ongoing review and a mid-term evaluation to enable adaptive management through the assessment of the effectiveness of the HCP’s strategies … Other motives for evaluation were to appraise the need for adaptation due to any major shifts in context (for example, fluctuations in financing, changes in government policy and new threats to values), contribute to the evidence base concerning Wunambal Gaambera Country and report on achievements to both traditional owners and external stakeholders.”

Plan for the future

Planning for sustainable futures is crucial for effective nation building.

Rather than responding reactively to any challenges, the most successful nations have a proactive, long-term and future-oriented focus. This means leaders must carefully consider whether any decisions being made for the nation fit in with long-term priorities. It requires a clear vision and strong process to ensure the nation building work can continue across generations.6Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), [link]

Planning for the future also means clearly defining the roles of your leaders and members in carrying out your group’s vision. It’s likely that these roles are different and involve various layers of decision-making. A strong collective vision of what you want for the future of your nation helps everyone understand and carry out their roles and responsibilities.

Leaders build for the future by mentoring youth who will carry on their work long-term. Make sure you have a succession plan and empower young leaders to contribute their new ideas now – not later. Read more about succession planning.

Yawuru man Peter Yu outlines four priorities for Yawuru in rebuilding their nation into the future.2Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 241-247. Each of these priorities is focused on the long-term growth and well-being of the Yawuru people:

Intergeneration transfer of Yawuru cultural knowledge

Yawuru have been ensuring the survival of their language and cultural knowledge through the Yawuru Liyan-ngan Nyirrwa Cultural Healing Centre, opened in 2019. The Centre focuses on the revitalisation of Yawuru culture and language through cultural and community development programs.

“It [the centre] will also provide an opportunity for senior and young Yawuru people to work together to develop an understanding of the value of mabu liyan and to ensure the transmission of knowledge and understanding of such Yawuru language terms.”

Investment in Yawuru young people

Developing the potential of their young people and nurturing their cultural identity is an important element of Yawuru nation building. Yawuru run an annual Youth Forum and offer youth scholarships that help mentor and support the next generation of Yawuru leaders.

“We recognise that investing in our young people is absolutely critical to transforming the old deficit discourse and achieving intergenerational change.”

Individual and collective wealth generation

Strategic investment of the monetary benefits received from their native title agreement has enabled Yawuru to pursue self-determined economic development. Their income generation strategies include a housing development model, the Yawuru Ranger Program, and the commercial operation of the Roebuck Plains Station, located 30 kilometers east of Broome. Each strategy focused on long-term cultural and environmental sustainability.

Building leadership for intergenerational growth and stability

In their work of nation-building, Yawuru recognise a need for leadership that can deliver stability and prosperity for future generations.

“Leadership is key to our social and economic transformation. We must rebuild the foundations of cultural knowledge and respect and integrate that into Yawuru contemporary governance, while at the same time develop the agility and resilience necessary to leverage opportunities to secure the economic future of our people in the emerging economy. This calls for a particular kind of public-spirited leadership, one that puts mabu liyan and the well-being of our people ahead of self-interest.”

Develop your networks

Create genuine strategic alliances with other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and non-Indigenous supporters. Experiment with networked and collaborative governance arrangements that will support your agenda.

Networking between Australian First Nations is an important source of support, advocacy and partnership in the work of nation building.

Read more about developing your networks in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander networked governance.

Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA) Partnership Principles

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA) facilitates partnerships and interactions with government and other external stakeholders on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri Nation.

To establish a coordinated approach for engagement with both local and state government, the NRA and the Ngarrindjeri Nation developed the Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan (listen to Ngarrindjeri speaking) agreement (KNYA). The KNYA is a formal framework for negotiation and participation between the Ngarrindjeri Nation and governments. It guides equitable Ngarrindjeri engagement in water resource research, policy development and management processes within the SA Murray Darling Basin region.6 Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority Inc, Submission by Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority Inc for and on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri to Murray Darling Basin – Royal Commission, May 2018, [link] Today, NRA has KNYA’s with the South Australian Government, Alexandrina Council, Coorong District Council, and Rural City of Murray Bridge.7 Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources and the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority, Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement (KNYA) Listening to Ngarrindjeri People talking, report 2014 and 2015, 2016, [link]

Ngarrindjeri people have also developed a set of Cultural principles and guidelines for research and engagement on Ngarrindjeri Country. These principles and guidelines provide advice to researchers and others on how to consult respectfully and meaningfully with Ngarrindjeri.

Building networks with other Indigenous Nations

The Ngarrindjeri Nation has worked to build networks and alliances with other Indigenous nations, including sharing their cultural principles and guidelines with the Gunditjmara people.

In October 2012, the Ngarrindjeri Nation and the Gunditjmara Nation met for an inter-nation summit in Kingston SE, South Australia. In 2015, another inter-nation summit was hosted by Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation at Lake Condah in Victoria. The purpose of the summit was to explore innovations in Australian Indigenous governance and develop a network for sharing strategies. Over 50 delegates from different nations, communities and groups around Australia attended.8 UTS: Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning Excellence in Indigenous Education and Research, “Controlling the Narrative: Nation Building in the Absence of Recognition,” 2016, [link]

The NRA, on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri Nation, has also worked closely with the Indigenous Nations and Collaborative Futures research hub at the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research. The research hub works collaboratively with Indigenous peoples and nations to provide education, research and consultancy in Indigenous nation (re)building, Indigenous governance and self-determination.9UTS, Jumbunna Institute of Indigenous Education and Research, “Indigenous Nations and Collaborative Futures,” [link] Between 2010-2022, a series of Australian Research Council funded research collaborations were co-conducted by Jumbunna Institute and the NNI, in partnership with individuals and groups from the Gunditjmara People and the Gugu Badhun, Ngarrindjeri, Nyungar and Wiradjuri Nations.10Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), [link]

The IPOA model of nation building

The IPOA – identify, purpose, organise, act – model is another strategy for effective nation building.

Many successful nations have followed the IPOA model in their nation-building journey. It was developed during an inter-nation summit of the Gunditjmara and Ngarrindjeri peoples in 2012. The IPOA model follows on from the IOA model – a similar model informed through decades of research across CANZUS countries:

- identifying as a nation

- organising as a nation

- acting as a nation.7Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), 21-22, [link]; Stephen Cornell, “Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government,” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 6, no. 4 (Sept 2015): 6, DOI: 10.18584/iipj.2015.6.4.4.

The IPOA model also identifies the purpose of the nation as a key step in nation building.

The IPOA model focuses on four interconnected and often overlapping stages of nation-building. Depending on your group’s context, you may find your nation building follows these stages in sequential order, you go back and forth between them, or some take place simultaneously. For example, organising as a nation may see people rethink or reflect on their identities as members of the nation. Acting as a nation may also make nation members consider whether their:

- rules, governing structures and decision-making processes help their nation to achieve its purpose

- nation is organised in a culturally legitimate way

- nation is organised according to the values of its people.

In this way, the stages of nation building can be seen as fluid and interdependent.8Larissa Behrendt, Miriam Jorgensen and Alison Vivian, Self-Determination: Background Concepts, Scoping paper 1 prepared for the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology Sydney, 2017), 29, [link].

– Adapted from Stephen Cornell, Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government, 2015.9Stephen Cornell, “Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government,” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 6, no. 4 (Sept 2015): 18, DOI: 10.18584/iipj.2015.6.4.4.

Identify

Nations are self-governing and politically organised groups. For nation building work to begin, the group must identify as a political entity – a group of people with a collective identity.

Identifying as a nation is all about considering the ‘self’ in self-governance. Who are the members of your group?

In some cases, identifying the ‘self’ might be a straightforward process. This may be the case if the nation’s identity remained largely intact throughout colonisation. In other cases, the collective self may not be as easy to identify. Members may have been displaced or dispersed, social and kinship relationships undermined, and cultural traditions damaged. This step may require careful consideration of the following questions:

- Who is the ‘self’ in self-government? Who is the ‘self’ in our self-determination processes?

- Who is our nation governing for? Nation members on Country? Those living ‘off’ Country? Extended family?

- Who is the collective ‘us’ we are referring to when talking about things like ‘our’ vision or ‘our’ goals?

- Does this collective ‘self’ result from a shared language, cultural practices, kinship structure, geography?

- Does this ‘self’ provide an adequate foundation for effective self-governance?

- What bonds hold us together as a collective?10Larissa Behrendt, Miriam Jorgensen and Alison Vivian, Self-Determination: Background Concepts, Scoping paper 1 prepared for the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology Sydney, 2017), 29-30, [link]

Purpose

This means understanding the nation’s long-term strategic vision and goals. The group must see that the vision and future aspirations reflect the nation as a whole. Not just the desires of a small minority within the nation.

Questions to consider:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- What is our vision and purpose? Do these reflect the nation as a whole?

- Does everyone in the nation have a clear idea of our vision and what we are trying to achieve?

- In twenty years, what do we hope is the same in our community or nation? What do we hope has changed?

- What sort of society, community or nation are we trying to build for our future generations?

Organise

Organising as a nation means developing, building or enhancing the institutional capacity needed to realise its goals. It’s about effective self-governance.

This might mean:

- creating institutions, rules and organisational structures from scratch, or

- restoring and reviving what already exists in the nation.

Taking the initial steps to organise as a nation will be different for every group, depending on where they are on their journey. It’s about customising the process to suit you. For some, this may mean:

- writing up an internal rulebook

- reviving language, or

- restoring culture as the foundation of building a culturally legitimate community.

For others, it might be speaking with Elders to develop a framework for nation building. It might also be deciding on a process of group decision-making, or coming up with a clear vision for how the future nation will look.

You need to consider whether you currently have the tools required to achieve your purpose.

While all nations have different governing institutions and processes, every nation must organise in a way that is culturally legitimate, transparent and supported by the community or group they serve.

This step often involves consideration of some very practical questions, like:

- What will our organisational structures and process of governance look like? Essentially, how should we govern?

- How do we make decisions and resolve disputes?

- Who has the authority to act on what?

Act

This is often considered the final step of nation building. Once a group has established a clear identity and developed its structures of self-governance, they are ready to act as a nation. This means asserting sovereignty and protecting the interests of the nation.

Self-determined action may include:

- strategically pursuing goals

- confronting problems

- responding to opportunities for the nation

- navigating any external partnerships.11Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), 22, [link]

Questions to consider may include:

- Who do we wish to be? How can we make that happen?

- How can we continue to expand our jurisdiction to gain full control of our affairs?

The Ngarrindjeri Nation in South Australia has used IPOA principles to regain control of their future and help dismantle ongoing effects of colonialism:

“To structure our narrative of Ngarrindjeri nation building, we draw on Pacific Rim Indigenous nation-building principles identified in the work of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development: identify, organize, act… Applying these principles to the South Australian context, we identify key features of the Ngarrindjeri Nation’s pathway to securing a future in the face of intense and complex forms of colonization …

For Ngarrindjeri to identify, organize, and act as a sovereign First Nation requires a theorization of contemporary forms of South Australian settler colonialism, the identification of their genealogies, and a clear understanding of the actor networks or assemblages that reinforce colonizing relations of power.”

Ngarrindjeri have a clear, collective identity that has remained strong despite the impacts of colonisation. Drawing on this clear ‘self’, the Ngarrindjeri Nation has been able to create the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA). The NRA is the peak governance body representing the Ngarrindjeri people. It helps develop new ways of interacting with the state government and reasserting Ngarrindjeri agency.4Steve Hemming, Daryle Rigney and Shaun Berg, “Ngarrindjeri Nation Building: Securing a Future as Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar (Lands, Waters, and All Living Things),” in Reclaiming Indigenous Governance: Reflections and Insights from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, eds. William Nikolakis, Stephen Cornell and Harry Nelson (Tucson: University of Arizona Press,2019), 73.

In 2006, the NRA came up with a ‘Vision for Country’. This vision became part of the ‘Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri Sea Country and Culture’.5Steve Hemming, Daryle Rigney and Shaun Berg, “Ngarrindjeri Nation Building: Securing a Future as Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar (Lands, Waters, and All Living Things),” in Reclaiming Indigenous Governance: Reflections and Insights from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, eds. William Nikolakis, Stephen Cornell and Harry Nelson (Tucson: University of Arizona Press,2019), 74. This provides a plan for the Ngarrindjeri Nation in pursuit of self-determination and a healthy future:

“Early in its inception, the NRA developed a Ngarrindjeri Yarluwar-Ruwe (Sea Country) program to take responsibility for this Ngarrindjeri transformative strategy, acting as a contact point for all non-Indigenous projects and engagements associated with Ngarrindjeri Yarluwar-Ruwe. The work of this program is guided by the “Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan” that encapsulates the Ngarrindjeri approach to identifying as a nation, organizing as a nation, and acting as a nation …”

The Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan is just one element of Ngarrindjeri nation building. Caring for water and natural resources remains a central component of the NRA’s work. For Ngarrindjeri people, this nation building journey has also been part of a wider movement of Indigenous rights and recognition:

“From the 1970s on, Indigenous people in Australia began to pursue an agenda of self-determination, land rights, and treaties. Ngarrindjeri leaders prioritized a process of nation identification, internal organization, and collective action directed toward the development of a healthy future for Ngarrindjeri people and for Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar.”

Another important aspect of Ngarrindjeri nation building has been the development of the Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement (KNYA). This roughly translates to ‘listen to Ngarrindjeri people talking’. The KNYA contract was negotiated by Ngarrindjeri leaders and the South Australian state government. It’s an example of how Ngarrindjeri have come together and – through their governing structure the NRA – act as a nation:

“Through this system of agreements, the Ngarrindjeri Nation acts as a nation: it uses law and negotiation to assert its unceded sovereignty and to protect its interests while building viable relationships with other governments.”6Stephen Cornell, “Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government,” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 6, no. 4 (Sept 2015): 17, DOI: 10.18584/iipj.2015.6.4.4.

You can listen to Professor Daryle Rignrey, citizen of the Ngarrindjeri Nation, talk about Ngarrindjeri Nation building. Remember, your own nation building journey will require you to customise these elements to suit the needs of your group.

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

Stay connected

Stay informed with AIGI news and updates.

.png)