To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Relationships

We look at some of the different relationships that you are likely to encounter when working in, with or for an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander group. We consider what a healthy relationship looks like, and how you can work to build and maintain them. We look at the networked governance style typical of First Nations relations and how to make the most of your networks. Finally, we cover strategic external partnerships and what to expect from an ‘ally’.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- What types of relationships are important for your group?

- What makes a relationship healthy? How can you build strong relationships?

- What are the connections you currently have beyond your own organisation, community or nation? How can you continue to maintain these networks?

- Does your organisation, community or nation have any principles for partnership-engagement?

- How do you connect with your members and other stakeholders? How are you accountable?

Types of relationships

Relationships are the strands that weave Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, communities and nations together. They make Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance distinct. Culture shapes the relationships that matter and why they matter.

When it comes to governance there can be a range of additional – and sometimes even competing – aspects to consider.

The analogy of a football team helps when thinking about some of the most important relationships in your governance.

The team captain needs to build and maintain a strong relationship with the team’s management. As the head of a team, the captain also needs to interact effectively with the players and the club.

In your group, the captain is your chief executive officer (CEO) and the team’s management is your board. The players are your management and staff, and the club is your members.

Keep in mind that there are many important relationships that exist beyond the ‘official’ relationships shown in the diagram. Certain people in your group – such as the CEO – have a responsibility to build and maintain these relationships. Often, these relationships relate to cultural, community and broader group interests. How important these types of relationships are to maintain depends on what you’re working to achieve.

In particular, the relationships between people working in organisations are greatly influenced by the cultural values of the members of the nations and communities for whom they are working.

Cultural relationships

Some examples of cultural relationships that you can consider include:

Family

For example, you have a sibling who would like to work for you. You’ll need to follow certain employment processes to make sure the process is fair, even though you know them and know they would do the job well.

Classificatory kin

For example, you are expected to avoid someone because of your kin relationship, but you have to navigate being their co-worker at the office.

Traditional owners or other custodians

For example, you need to defer to their authority and check it’s okay for you to visit a particular area and do certain work even though – as a staff member – you have a lease or official permission to use the area.

Elders

For example, you are expected to follow the direction of someone culturally senior to you, even though you are their manager within the group.

Law leaders

For example, you are obliged to get guidance or the okay from senior law leaders before making a decision that’s technically ‘yours’ to make, as CEO.

Community relationships

Some community relationships may need to be considered at the individual and organisational level:

- Geographic community you are situated within – for example, you’re a small business enterprise – such as a food co-op or local fashion label – and it’s in the interests of your community to know that you are local and invested in your local community.

- ‘Sector’ community you sit within or is relevant to your work – for example, you’re a community health clinic and it’s in your interests to maintain a relationship with other clinics in your region so that you can work together on advocacy projects.

Wider environment relationships

There are also wider environment relationships:

- Government (local, state, federal members, agencies and ministers with relevant portfolios) – for example, for them to know who you are and what you’re about so that you can build a reputation for future partnership opportunities or grants.

- Philanthropic – for example, families, charities or businesses that would be interested to see your group prosper, and be interested in supporting this.

Together, these relationships help shape the governance environment specific to your circumstances.

The above cultural, organisational, community and nation relationships are just one way to look at the relationships that are important for your group to consider.

Another way could be to divide relationships into internal (those inside your group) and external (all others).

You could also think about relationships in terms of your position and who you are accountable to. Another way to think about it is by considering the network of relationships you’re a part of.

Whatever way you choose to look at your relationships, consider existing and potential relationships and their part in working towards your group’s objectives. This will help you work out which relationships have priority for you, and how much effort should go into building and maintaining links.

Wearing many hats

Organisations, communities and nations are always seeking to make the most of their resources, as well as the talent and experience they have among their members.

Many people – especially those with strong leadership skills or people who are respected within a community – often find themselves wearing multiple ‘hats’. For example, one person can:

- sit on the local land council board

- be active on a school committee as a parent

- be called to help with activities as a respected Elder within the community, and

- work full-time at the health clinic.

These various roles, and the responsibilities that come with each, can easily become complicated to manage. A person needs to be aware of their obligations and work out ways to maintain relationships depending on what hat they’re wearing.

The hat might determine whether it’s appropriate to talk to a family member about land council board business. Or whether to talk to other parents on a school committee about the health status of someone who has visited the clinic.

The below definitions may help to understand the sometimes blurred boundaries between personal, professional, kin, and strategic relationships:

Personal relationships

Personal relationships are based on your individual, non-work-related ties to family or friends. If you work with a friend or family member, it can sometimes be challenging to keep your relationship professional while at work.

Your friend or family member may want to talk about matters that aren’t work-related. You need to use your discretion to keep the personal from interfering with your work.

Kin relationships

Kin relationships are family related, but can be slightly different from personal relationships. Kin relationships sometimes have obligations to fulfil, and sometimes they have avoidance practices that must be followed. Even though it can be challenging in the workplace, you might still have cultural obligations to uphold.

You may work with an aunty or uncle, and you must respect and honour their cultural seniority, even if you hold a higher position in the workplace. If this is challenging, discuss with someone appropriate how to navigate the relationship while you’re at work.

Professional relationships (or partnerships)

Professional relationships are based on work-related interests. Professional relationships have certain standards that must be upheld. If a discussion or proposed action with someone is work-related, then you should follow the rules that govern professional relationships in your workplace. This is true even if you’re working with a friend or family member.

Strategic relationships (or partnerships)

Strategic relationships can be at the level of individuals, organisation to organisation, entity to entity, and so on. What makes it strategic is that it’s understood the relationship is beneficial for both parties.

Usually, the basis of the relationship or partnership is clearly defined and acknowledged. If there’s any doubt about the benefits to one or more of the parties involved, you should raise this with the appropriate people.

Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation is actively engaged at the community level, offering practical support to families on community concerns such as mental health, suicide prevention, petrol sniffing prevention, and parenting. There is a strong feedback loop between Waltja’s directors, members, community and staff. Directors talk to community and share feedback with Waltja’s executive team. Waltja’s staff are invited to engage with community and meet directors and families. By hearing from families directly, Waltja has a better understanding of what the needs of their communities and members are.

Waltja’s governance is customised to suit community, and means giving directors a hands-on role in identifying community needs and making decisions around program delivery. With the guidance of directors, Waltja has delivered tailored programs across central Australian communities, including services like Reconnect Youth, the Family Mental Health Support (FMHSS) program, Children and Family Intensive Support (CaFIS) program, and their Art, Language & Culture programs.

Build and maintain healthy relationships

Healthy relationships are critical to the networked success of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, communities and nations. Maintaining healthy relationships among the people inside and outside of your group takes work.

There are fundamental ingredients that generally help with building and maintaining healthy relationships across all groups.1Alfred Tallia, Holly Lanham, Reuben McDaniel and Benjamin Crabtree, “Seven Characteristics of Successful Work Relationships,” Family Practice Management, 2006, [link]

Ingredients for a healthy relationship

What does a ‘healthy’ relationship look like, and what can you do when some of the key ingredients are missing or weakened? Depending on the nature of the relationship, the answers to these questions vary. For example, manager to employee, CEO to external stakeholder, organisation to organisation.

Relationships are not static – they change over time. This can happen because of a breakdown in some or all of these ingredients, changing ‘hats’ or new personalities.

If any of the key ingredients are missing, think about why this might be and what could be done to restore these to the relationship.

If you see that a relationship is not working as well as it could, it can also help to go back to basics. Think about:

- what the aim of the relationship is

- what the parameters of the relationship are

- why it matters to keep it strong and healthy.

Trust

Where there is trust, people can work together more easily and effectively. Trust is about being honest, transparent, upfront and ‘true to your word’. This may include asking for opinions or perspectives and sharing yours. It may extend to being open to successes and failures. Conversely, actions such as lying, hiding information, or not being available in times of need instead of dealing with difficult situations head-on, corrode trust in a relationship.

Respect

Respect generally involves being considerate and tactful of the interests, feelings and values of others. It may include welcoming differences of opinion or being open to new ideas. Avoiding gossip is a good way to build respect and trust. When you talk poorly about someone who isn’t present, those that do hear will probably assume you’ll do the same about them. This can damage your relationships.

If you have an issue with someone, the best approach is to raise it with them directly – in a respectful manner.

Communication

If you have concerns, problems, or are really pleased with the way things are going, it’s helpful to make this clear. Strong, clear communication channels, such as knowing where each party stands on a particular issue and understanding why, are key to avoiding misunderstandings and unnecessary disputes. Keep in mind that listening is a big part of communication.

Understanding

Related to communication, understanding means knowing what the basis of the relationship is and why it matters to both parties. It’s also about being clear on your roles and the extent of any obligations. Look for official documents such as policies, Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs), or position descriptions if there’s uncertainty around expectations.

Understanding also extends to having perspective on why a person is doing something in a particular way, or why something concerns them.

Reciprocity

Healthy relationships are a two-way street. There should be balance in what each person or group gets from one another. It might help to reflect on what you have to give that they value, as well as what you value about having the relationship. If the benefits are skewed in the favour of one party, it might be worth thinking about how you can work to improve this balance. Be accountable and hold others to account, if necessary.

Managing relationship boundaires

Healthy boundaries in your relationships make it possible for you to work and interact with others more successfully. It’s also a key element of effective governance. This is particularly important when it comes to the relationship between your board, management and staff.

To have a sound strategic relationship between the board, management and staff:

- Have clear boundaries in policy documents for different roles, their responsibilities, and their power.

- Reinforce a wide understanding and appreciation of the group’s policies and the roles and responsibilities of particular positions. For example, through inductions, training activities and regular review of codes of conduct.

- Realise the importance of clear communication – including making the time to meet and discuss issues, and allowing for regular feedback opportunities.

- Have processes to deal with behaviour that’s outside what’s expected or acceptable within a particular role.

You can also take a similar approach to managing relationships with external professionals, such as consultants.

Relationships with professionals

There are some general guidelines that your organisation, community or nation can use when engaging external professionals.2J Graham and M Bassett, “Building Sustainable Communities: Good Practices and Tools for Community Economic Development,” 2005, Canada, [link] The information below is aimed specifically at building and maintaining relationships with externally engaged professionals.

Identify good experts

Check the professional websites of the people you want to engage. Read and evaluate their code of conduct and ethics guidelines.

Use your existing networks

Ask other communities to find out about people’s experience with the same professionals.

Check references

Conduct a face-to-face interview where possible, and ask for samples of their previous work.

Choose someone who’s keen

Look for people who show a genuine interest in your group, who are committed to spending the time that you need on your projects, and who want a long-term relationship.

Engage people who have a proven track record

Look for someone who has experience in working on the issue, and in writing reports in a style that’s easily accessible to your members.

Balance cost with efficiency

Remember that university academics – whose costs are normally covered by their institutions – usually cost much less than consultants. But a consultant may work more quickly and efficiently.

Establish effective contracts or other forms of agreements

These may vary according to whether the work is voluntary or paid. You may have to call for competitive bids. You may get better value by engaging someone who costs more, but has experience and expertise in dealing with a particular issue or has worked with the community for a long time.

Start with a small contract or project as a test run

Begin with the understanding that good work and relationships can lead to larger projects or assignments.

Develop clear terms of reference in the contract

Do this right from the start, and include specific deliverables, methodologies and timelines.

Keep the contractor fully informed

Give the contractor the protocols to use when consulting with members or stakeholders, and your group’s policies and code of conduct.

Get agreement on the content of reports

When you need a written report, make sure the contract or agreement states that the contractor should discuss the contents with management before writing the report.

Make sure costs of the work meet industry standards

Competitive bids may help, but it’s also a good idea to check daily rates and the time estimated for each task.

Check who is doing the work

Clarify in the contract the time allocated for the senior and junior experts. Also clarify how much they will contribute to training and mentoring people within your group.

State a maximum cost for the work

If there are extensions or additions to the work, make sure these are confirmed in writing and that a new cost is firmly established.

Make someone in your group responsible

Allocate a specific person in your group to monitor the contract or agreement.

Conduct a face-to-face exit interview

As well as a written report, it can be helpful to have a face-to-face exit interview with key leaders, management and the expert to discuss their findings.

Get feedback from the contractor

When the work is finished, get feedback from the contractor about the whole process and how they think it could have been improved. Also get feedback from your group’s members who were involved.3J Graham and M Bassett, “Building Sustainable Communities: Good Practices and Tools for Community Economic Development,” 2005, Canada [link]

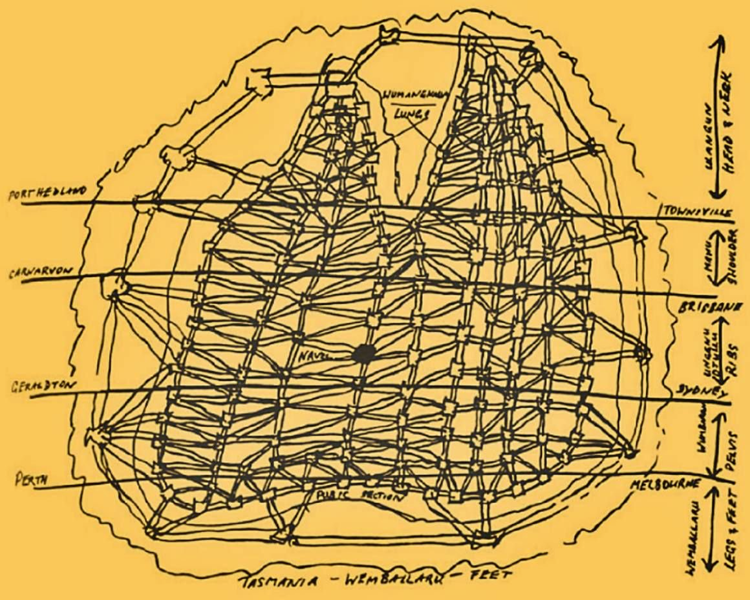

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander networked governance

A network is a connected group of people with similar interests or concerns who get together to work and support each other.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culturally networked governance is dynamic and sophisticated. It has:

- interdependent connections between people, places and things (past, present and future)

- layered systems of representation and leadership

- overlapping memberships and authorities

- dense systems of relationships and mutual responsibility

- layers of decision-making, accountability and authority.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups often have a preference for local control of decision-making, action and responsibility. At the same time, local networks are usually flexible and open-ended. The advantage of such networks is that governance arrangements can:

- link across other similar scales of networks – for example, across several outstations

- scale up vertically – for example, to form larger federations and alliances.

This means that even local networks are directly connected to many other surrounding parts. Each part will have bridging relationships and shared goals that connect it outwards to the governance networks of other groups.

Networked leaders

‘Visible’ leaders of groups are usually part of wider networks of leaders and extended families. These often spread well beyond their own group. Networked leaders are people who can:

- consider multiple options and ideas

- facilitate connectivity

- call upon others for support and knowledge

- mobilise community support.

This is a more sustainable form of leadership for the type of governance needed for development. It is this kind of networked logic and leadership that lies at the heart of Indigenous cultural principles of governing and leadership. It also informs the ongoing work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander initiatives in community and nation building.

You can read more about networks of leaders.

Illustration titled ‘Bandiayan: the continent’ by David Mowaljarlai reproduced from the book Yorro Yorro: Everything Standing Up Alive by David Mowaljarlai and Jutta Malnic, Magabala Books, 1993.

Networks improve governance

Networks and networking can improve your governance in many ways. Use networks to:

Foster constructive solutions

Two heads are better than one. Strong networks can help you develop ideas. They also allow you to share knowledge and best practice.

Be flexible and responsive

Networks adapt how they work to suit the issue at hand or to accommodate future potential.

Create close relationships

Networks allow organisations, communities and nations to develop strong ties with other individuals or groups. They allow for shared priorities and goals. In doing so, they encourage better accountability to members of the network.

Provide a source of information and support

Networks facilitate sharing and discussion of issues of common interest – such as new laws and regulations, or technological developments.

Make decisions legitimate and easier to implement

Generally, decisions made among your networks will represent a consensus of views of a broad group of people. They might take longer, but are likely to be more sustainable and widely supported

Link the national and regional to the local level

Networking brings different players together – communities, regional and national agencies, governments and organisations. This is often important for small remote groups.

Build new skills

Having strong networks can make new skills and resources more accessible – through outside experts, shared knowledge, staff exchanges and secondments, and mentoring.

Benefit from economies of scale

Networks can share costs and scarce resources, assets and capacities. They facilitate wider agreements and partnerships.

Improve your reputation

Networks can help your group become more visible and build your reputation – locally, in other cities or even overseas.

Girringun Aboriginal Corporation was awarded Highly Commended Category A in the 2014 Indigenous Governance Awards. In this video, CEO Phil Rist outlines how Girringun’s leadership fostered a common goal to bring nine tribal groups together. By working together as ‘one voice’, and building relationships with surrounding stakeholders, Girringun established a form of contemporary sovereignty.

“We represent 9 tribal groups, over a pretty huge area in North Queensland. We’re not a land council or an Indigenous legal service, or a health service, we’re just a bunch of Traditional Owners that have managed to really come together as one community, one organisation and formed this very strong, effective, powerful Indigenous NGO at the grass-roots level … And not much happens in our area without us knowing about it because we have built this relationship with all those different partners, government and others, and they as well act as if sovereignty exists within our area.”

– Phil Rist, CEO

Expand your networks

Expanding your networks means more groups and individuals can be involved in your governance, bringing with them different strengths and expertise. It’s important to continually engage with wider networks, as well as your local networks.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups have successfully expanded their networks by:

Including their community

- Considering who in your organisation, community or nation would be a useful contact for your board. Think about how you reach out to your community.

Keeping people informed on all levels

- Make sure all organisation, community or nation members would be able to explain your governance to an outsider.

Advertising their governance

- Think about where you can advertise your governance, outside of businesses or organisations. Also think about how you can advertise within your board.

Having someone spread information in remote areas – in person or using the Internet

- Consider how people outside of your organisation, community or nation find out about your governance.

Diversifying their board of directors

- Think about what cultural connections you have within your board of directors. Can you use these connections to spread the word about your governance?

“For Indigenous people, both prior to and after colonisation, our very survival as individuals and as distinct cultures has depended on our commitment to remaining connected to each other…

Connectivity is part of our identity, of how we think about ourselves as forming part of a constellation of responsibilities to a wider network of kin and to country…

In our language, Yawuru, the term used to describe the interconnectedness between oneself, the wider community and the natural landscape is ‘liyan’. Mabu liyan equates to a sense of well-being and living the ‘good life’.”

– Peter Yu, Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation, 2021.4Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 234.

Maintain your networks

Maintaining relationships with your key networks is important. Building governance capacity – of individuals or groups – is greatly strengthened when it includes long-term support from your wider networks.

Some of the relationships in your networks will be enduring and close – such as your members and partners. Others are short-term and issue-specific – such as professional advisors, consultants, casual contractors, volunteers and bureaucrats.

Some relationships may be informal and based on common interests or simply a willingness to help. Others may be formalised through written partnerships, contracts, grant conditions or agreements.

It’s likely that the people or groups you have governance relationships with will have very different values to your own. It’s also likely that you’ll experience challenges within your networks. With the appropriate time, effort and resources, you can manage these challenges effectively.

To make sure your networks give you the best support for your governance, here are some challenges to watch out for, and some solutions to help address them.

Making decisions

Some networks aim to reach consensus decisions – that is, all parties agreeing. But sometimes a single party may disagree, stopping a decision being made or later undermining it.

Solutions:

- Clearly identify how decisions are made when consensus cannot be reached.

- Encourage wide support for and the legitimacy of the decision-making process.

- Have rules for ‘majority consensus’ and confidentiality to improve implementation.

Becoming complacent

Networks can run the risk of becoming complacent, operating only in their comfort zone. They may also become bureaucratic and inflexible.

Solutions:

- Make sure it’s someone’s role in the network to seek new opportunities.

- Arrange informal social and cultural activities.

- Meet with other groups, communities and organisations to exchange contacts and ideas.

Accountability can become dispersed

Accountability may become more difficult to monitor in large networks because decisions are made at many different points. Large networks are also more likely to lose touch with outlying members.

Solutions:

- Make sure that the roles and responsibilities of the different parts of your network are clearly defined and understood.

- Make sure that the accountability of network participants and processes is clear and agreed to by everyone.

Getting new skills

Setting up new partnerships may require entirely new skills and knowledge. They may also come up against resistance from the existing network.

Solutions:

- Do an internal audit to work out if you have the people with the right skills for the partnership activities.

- You may need to recruit or connect to people with new skills, contacts and relationships.

- Share knowledge and plans between existing members through regular open communication.

- Make partnerships with parties who have a good reputation for strong governance and creative solutions.

Becoming competitive

Networks between groups or organisations with similar functions, memberships and funding sources may become competitive rather than collaborative.

Solutions:

- Build trust across your networks – for example, by sharing resources, or by making joint decisions on issues that concern you all.

- Encourage more open, accurate and easy exchange of information across the network.

Losing control

Leaders and managers risk losing control of their own agenda if key stakeholders in your network – government, non-government organisations or industry groups – have different ideas and priorities.

Solutions:

- Analyse the different concerns and issues of each stakeholder and how they influence your governance processes and outcomes.

- Decide what parts of your agenda or goals are non-negotiable, and those you want to collaborate on.

Working in partnership

Effective groups do not operate in isolation. The ability to represent your community, form partnerships and communicate with others is an important part of achieving your group’s goals and vision. This ability is strongly aligned to having leaders whose style of working is collaborative and connected up.

It’s crucial you have ground rules to make sure that any strategic relationship is maintained to a level that meets your needs and expectations, regardless of the comings and goings of individual staff. We refer to these relationships as partnerships.

A partnership means having a collaborative association with another community, organisation, company, institution or agency, that usually shares a common interest. A partnership may be legally binding or informally endorsed.

Benefits of working in partnership

Developing strong partnerships is a way to increase collective knowledge and skills. For some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, working in partnership is an important step towards empowerment and the exercise of self-determined governance. Indigenous nations have a long history of establishing treaties, agreements and alliances with each other well before settler colonisation. These are forms of traditional cultural partnerships.

Establishing partnerships and strategic alliances with external organisations – such as service providers or research institutions – allows Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups to have a greater impact outside of their own community.

Applicant organisations in the Indigenous Governance Awards (IGA) noted that effective partnerships led to other benefits, including:

- program alliances – such as collaborating on specific projects

- knowledge partnerships – including sharing of information and collaborative research activities

- strategic relationships – such as high-level advocacy and enhanced dialogue.

“A major achievement for the Djillay Ngalu Health Consortium relates to the fact that it has been operating as a consortium for 10 years. The four ACCHOs [Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations] have collaborated on many projects over the past 10 years and developed high-quality working relationships with the mainstream health organisations … creating culturally safe mainstream health services that allow [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People] greater equity of access and an ability to choose a range of services that would not normally be the situation if these partnerships did not exist.”

– East Gippsland Aboriginal Health Consortium, Djillay Ngalu Category B Shortlisted Applicant, Indigenous Governance Awards 2016.

Risks of working in partnership

Entering into partnerships requires careful consideration and then governance of the relationship.

The Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission (ACNC) identifies several risks that come with charities working in partnership.5“Governance Toolkit: Working with partners,” Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, accessed May 2023, [link] Many are transferrable to organisations, communities or nations more broadly. Risks include:

- the partner organisation’s vision, mission or values not aligning with your group

- the partner organisation having different expectations of the purpose and operation of the partnership

- conflicts of interests

- fraud and corruption

- problems in the supply chain – such as exploitation and abuse

- lack of transparency between partner organisations

- the partner organisation being incapable of doing what the agreement requires

- disputes.

These risks can impact your staff, members and other stakeholders, and can cause damage to your group’s reputation. They can result in a failure to achieve what you set out to achieve in the partnership. They can also result in costs to rectify any damage done, including possible litigation.6“Governance Toolkit: Working with partners,” Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission, accessed May 2023, [link]

ACNC has a guide for working with partners. It includes resources to help review a partnership and assess the benefits.

Creating a balanced partnership

The term ‘partnership’ suggests equality. Partners may expect equal control of the benefits from an arrangement. However, for many First Nations groups, partnerships are often less equal. This may be because they face rigid funding arrangements tied to outsider objectives and interests. Or, they are invited to be involved in ‘consultation’ processes without any meaningful control over the nature of their relations with external parties. For example:

- with government agencies – such as service delivery and land management

- with businesses – such as mining companies, art galleries, tourism

- with universities – such as research projects.

Creating a balanced partnership can protect you against being taken advantage of or treated unfairly, or giving more than you get. Successful partnerships have trust, respect and honesty at their core. Both partners need to:

- recognise the contribution the other makes

- know and accept each other’s differences

- identify what they are trying to achieve together

- commit to a plan of action.

Sometimes, your group’s interests may differ or diverge from those you are entering a partnership with. There are many ways of balancing different interests. Some common approaches to creating a balanced partnership include:

- Developing a formal agreement, a settlement agreement, a contract, a Treaty, a memorandum of understanding (MOU), or a ‘collaboration plan’. The approach that is right for your group will depend on your circumstances.

- Identifying what principles you would expect any potential partners to follow. This helps you know what to ask for or what to accept when you’re approached by or looking to engage in a working relationship with an external party.

- Building in regular feedback, evaluation and review processes to partnership conditions. It’s a great way to make sure agreed terms of engagement are taken seriously. Both parties can track how they are going with sticking to the agreed terms, make any necessary adjustments. And they can be held accountable if they’re not upholding their end of the bargain.

- Reviewing ways of working. For example, when it comes to research partnerships, the research methodology can greatly impact your level of control over what is researched, how research is done, and who owns the data that is produced.

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) champions a partnership model shaped by the Martu cultural value of Kujungka which emphasises collaboration between Martu and non-Martu as equals. This approach harnesses the complementary skills and knowledge of both groups, fostering a shared commitment to addressing the needs of Martu communities effectively.4 Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ), “Our values”, accessed November 2024, [link]

Building genuine intercultural partnerships is central to KJ’s philosophy. The organisation emphasises mutual respect, understanding, and a willingness to learn from one another.5 Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and SVA Consulting, *Kujungkarrini: How to Achieve Aboriginal Policy Objectives. A study of the Martu Leadership Program as an example of putting policy objectives into practice, 2024, 21.

One key initiative is the on-Country cultural immersion camps, where participants such as the local Magistrate, the Commissioner of WA Police, Aboriginal Legal Service representatives, and other senior police and justice staff are invited to spend time with Martu. These immersive experiences allow non-Martu with the opportunity to deepen their understanding of Martu culture, people and aspirations, as well as build meaningful and lasting relationships.

“This is the first time I can truly say this immersive experience over five days, you cannot help but grasp, taste, feel, and learn much more about Aboriginal culture…but to be alongside some of the Martu people and Elders who have walked in off the desert in my life time and sit and listen to their wisdom and their willingness and yearning to improve the lives of Martu people, is such a rich experience.”

-Chris Dawson, then Commissioner of WA Police (2018)6 Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and SVA Consulting, “*Kujungkarrini: How to Achieve Aboriginal Policy Objectives. A study of the Martu Leadership Program as an example of putting policy objectives into practice”, 2024, 22.

The Aboriginal Governance and Management Program (AGMP) provides governance and management support to Aboriginal organisations in remote communities throughout the Northern Territory (NT). They have developed a set of straight-forward Partnership Principles (PDF 421KB) for non-Aboriginal organisations looking to work with Aboriginal organisations and communities in the NT. These principles may also be relevant for groups across Australia.

Allyship

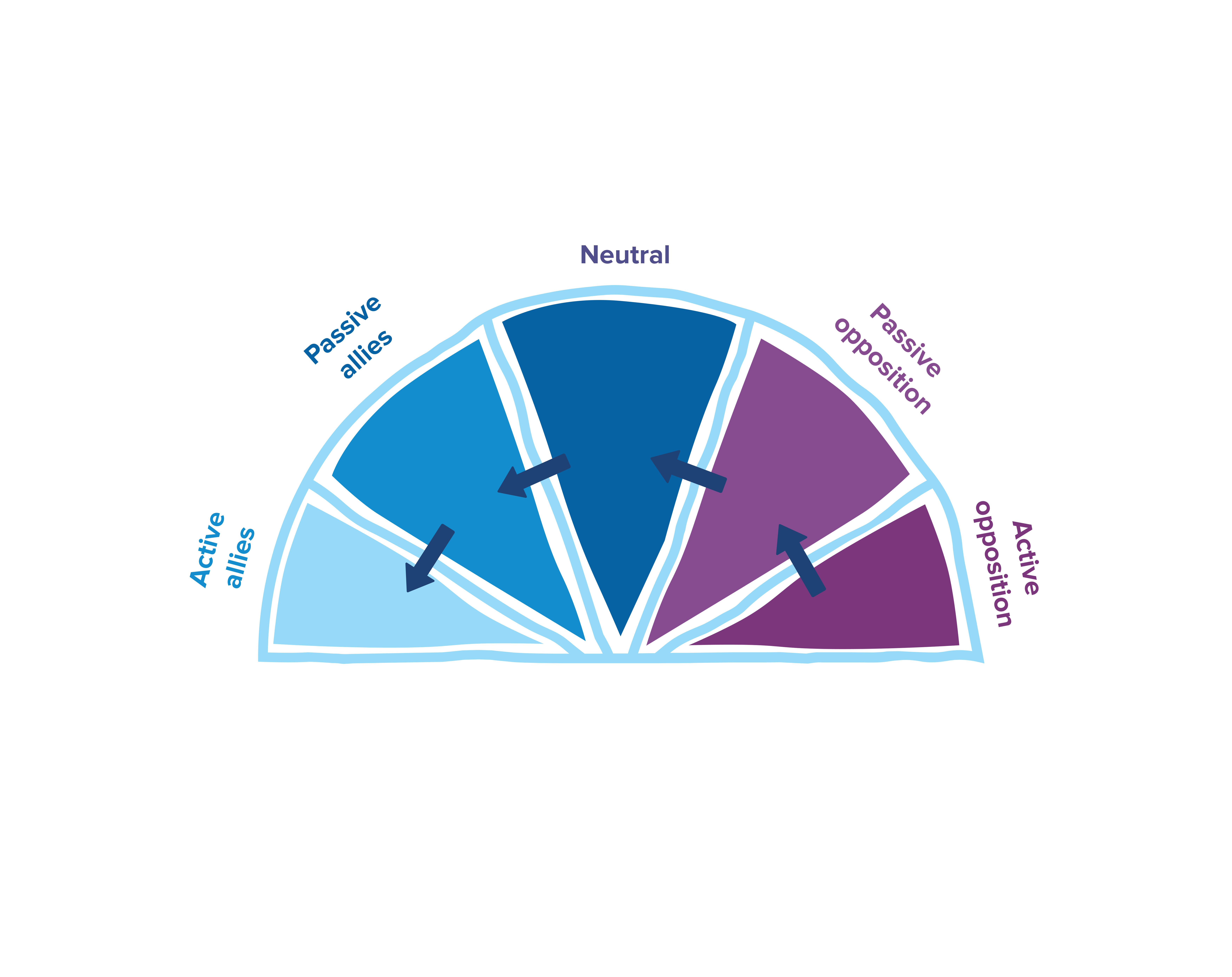

The Close the Gap Report describes an ally as ‘an individual or a group who possess structural power and privilege and stand in solidarity with peoples and groups in society without this same power or privilege’.7Lowitja Institute, Close the Gap, Transforming power: voices for generation change (The Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee, 2022), 34, [link]

First Nations groups and people who make up a minority across Australia may benefit from effective allied relations. To benefit, you need to recognise what strong, proper allyship looks like. You must also be able to recognise when a purported ‘ally’ might be falling short.

According to Close the Gap, the most effective partnerships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and others are underpinned by allyship. They are built on trust, accountability and a ‘decolonised approach’.8Lowitja Institute, Close the Gap, Transforming power: voices for generation change (The Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee, 2022), 34, [link] A decolonised approach is about encouraging people to explore their own assumptions and beliefs. Especially dominant or non-Indigenous thought, which is often assumed to be superior. It’s also about opening up to other ways of knowing, being and doing – such as those that are distinctly Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.9Juanita Sherwood and Tahnia Edwards, “Decolonisation: a critical step for improving Aboriginal health,” Contemporary Nurse 22, no. 2 (2006): [link]

“If equitable, partnerships can be transformative, creating a safe and supportive environment to effect change, and a way for non-Indigenous individuals and organisations to practice allyship and support the voices and self-determination of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.”

– Close the Gap, 2022.10Lowitja Institute, Close the Gap, Transforming power: voices for generation change (The Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee, 2022), 34, [link]

Close the Gap also provides some guidance on what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, communities and nations should expect from their strategic partnerships – both at an individual and organisational level.

The report explains that being an ally is an ongoing, strategic process. It’s a process that requires an ongoing commitment to:

- critical reflection

- education

- listening

- action.

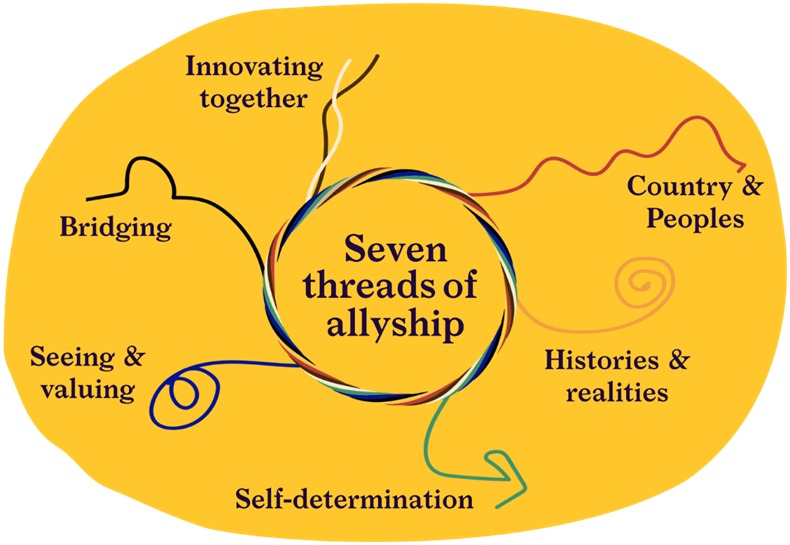

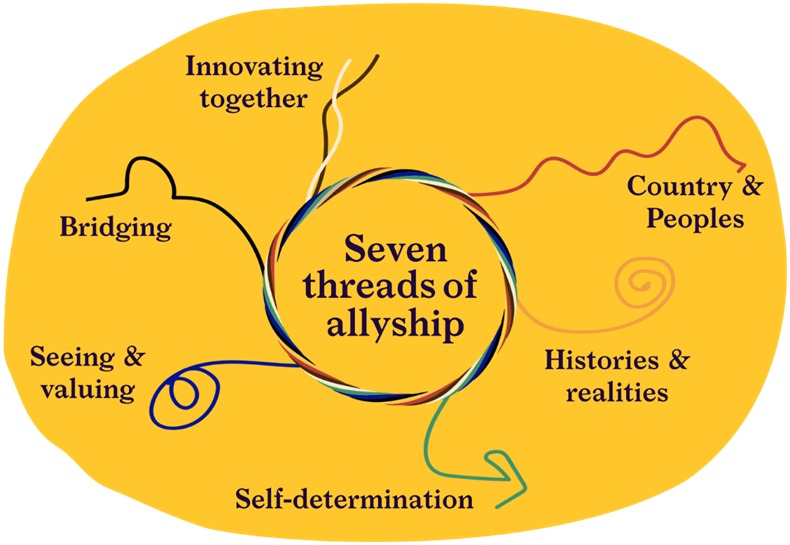

For non-Indigenous organisations and individuals wanting to strengthen their relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, the Many Threads Framework has more information on best practices for effective allyship. The ‘Seven Threads Prompt Book’ provides a range of practical prompts. It was developed with the guided perspectives of Uncle Tony Lovett, Aunty Vickey Charles and others.11The Australian Centre for Social Innovation, Many Threads Prompt Book, 2022, [link]

Seven threads of allyship (2022) – The Australian Centre for Social Innovation.

There are resources that you can direct potential partners to. These resources can help make sure partners understand what’s expected of them as an ally. You may also find them useful for thinking about, and articulating, your own group’s standards for engagement:

- Close the Gap (2022) Transforming Power: Voices for Generational Change

- Amnesty International (2022) ‘10 ways to be a genuine ally to Indigenous communities’

- TACSI (2022) Our seven threads prompt book for First Nations Allyship

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

Stay connected

Subscribe to AIGI news and updates.

.png)