To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Understand peacemaking

This topic defines peacemaking for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups. We also look at the role of healing in peacemaking.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- What terms does your group use when talking about dispute or conflict resolution?

- Does the term ‘peacemaking’ have any relevance?

- Do your peacemaking processes consider the procedural, emotional, and substantive needs of those who are involved?

- In what ways can peacemaking facilitate healing within your group?

Defining peacemaking

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives on responding to conflicts, disputes and complaints can be quite different to non-Indigenous approaches.

Some documented practices use language – such as ‘peacemaking’ – to describe processes and approaches that aim to reconcile differences and promote harmonious relationships between groups and individuals.1Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and ADR,” [link] It’s a dynamic and ongoing process that requires commitment, collaboration and engagement with the wider community.

Your group’s peacemaking processes should draw on your cultural knowledge, values and traditions. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, peacemaking also means embracing a deeper level of healing and restoration.2Toni Bauman, Juanita Pope, David Allen, Margaret O’Donnell and Rhiân Williams, Federal Court of Australia’s Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project, Solid work you mob are doing: Case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report to the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (Barton, ACT: National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, 2009). Peacemaking is often used to describe dispute resolution and conflict management processes, mediation and the healing of internal relationships.

Resolution and management are integral components of peacemaking. Resolution is about resolving (fixing) the issue at the core of a conflict, dispute, or complaint. This approach to peacemaking aims to address specific issues and achieve final agreements that both parties agree to.

When a resolution cannot be found easily or quickly, then management may be useful. The goal of management is to find ways for people to work together – despite their differences – respectfully and productively.3“Conflict Management vs Conflict Resolution,” ADR Times, June 2021, [link]

In this Toolkit, the language of peacemaking includes all forms of conflict, dispute, and complaint resolution and management. It is important that these approaches are customised so that they incorporate your language, culture, and values.

Keep in mind that there may be smaller disputes that make up parts of a broader conflict that can be separated out and resolved, while other aspects remain more difficult to address.

Members of the Gununa community on Mornington Island (the largest of the North Wellesley Islands) recall how certain Elders – known as ‘Muyinda’ – played the part of peacemakers or ‘justices of the peace’ in the past.5Morgan Brigg, Paul Memmott, Philip Venables and Berry Zondag, “Gununa peacemaking: informalism, cultural difference and contemporary Indigenous conflict management,” Social & Legal Studies 27, no. 3 (2017): 352, [link]

Their role was to ‘promote peace, to prevent violence and manage grievances’. This includes what are sometimes called ‘square-up’ fights.6Morgan Brigg, Paul Memmott, Philip Venables and Berry Zondag, “Gununa peacemaking: informalism, cultural difference and contemporary Indigenous conflict management,” Social & Legal Studies 27, no. 3 (2017): 352, [link]

This partly physical dispute resolution process was controlled and contained to make sure the ‘square up’ was in proportion to the issue. The aim was to restore social harmony and make sure that those involved could move forward without ill feeling or an ongoing grudge.

The ‘square up’ process shows how traditionally valued events aimed at minimising physical harm and restoring relationships following conflict have a long history in parts of Australia.

While ‘square up fights’ are less common nowadays, the process of involving the Elders and family – with an emphasis on restoring harmony – remains strong. It continues to shape the Gununa community’s peace-making model.

In 2008, a peacemaking service called the Mornington Island Restorative Justice (MIRJ) project began. The MIRJ project works with Indigenous families to resolve disputes in a way that respects local culture and is accepted by the formal justice system.7“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander justice initiatives,” Queensland Government, updated February 2021, [link] During the project’s initial consultations, Gununa community members agreed that externally imposed peacemaking processes were not a suitable solution. Instead, there was a need for culturally appropriate and locally controlled processes.

The MIRJ project uses mediation to resolve disputes, with the help of an impartial third party. Community members see mediation as similar to the customary process of ‘square- up’. The community developed a set of rules and an 8-step kinship-based mediation model. This model draws on key principles of both mainstream mediation and customary ‘square-up’, including:

- voluntary participation

- mediator impartiality

- participant safety

- fair treatment and respect

- involvement of Elders and family relationships

- participants are free to choose their mediators.8Morgan Brigg, Paul Memmott, Philip Venables and Berry Zondag, “Gununa peacemaking: informalism, cultural difference and contemporary Indigenous conflict management,” Social & Legal Studies 27, no. 3 (2017): 352, [link]

Sustainable peacemaking

Getting people to agree can sometimes seem easy. People may say they are satisfied when in fact they are not. It’s important that peacemaking leads to long-term change. This often requires informed consensus.

Informed consensus involves people reaching agreement in a way that may have involved compromise. All parties understand what they have agreed to and why it is reasonable or necessary.

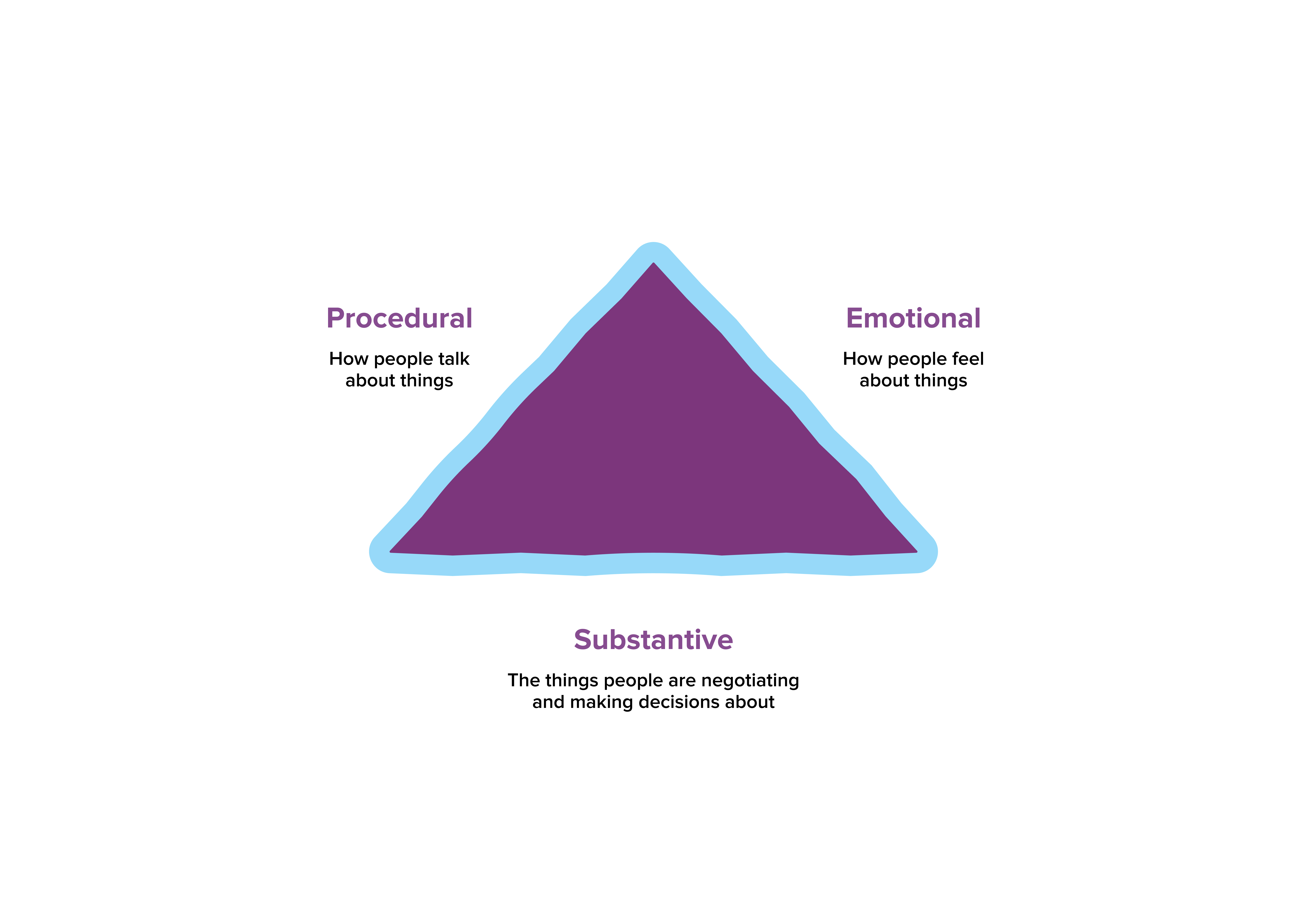

To make sure peacemaking can be successful in the long term, consider the ‘satisfaction triangle’. This is a simple concept that outlines three needs to consider when working through conflict.

While it may not be possible to please everyone all the time, thinking about these three needs can help move people out of dispute mode and into more cooperative behaviour.

To get long-lasting results from peacemaking, people’s procedural, emotional and substantive needs should be addressed.

Procedural needs (the how)

Considering people’s procedural needs is about making sure the group sees peacemaking processes as fair. Those involved have had the opportunity to take part, put forward their views and be listened to. They have confidence in the information, rules and processes of the group.

Emotional needs (feelings)

Emotional needs are about considering the feelings of those involved. This includes people’s personal and emotional reasons for the conflict, dispute or complaint. And whether they feel these have been considered in the peacemaking process. It also means considering how they feel about themselves and others when outcomes are negotiated.

Substantive needs (the what)

Substantive needs relate to the actual issues or things that people in the dispute want resolved. These can be tangible – for example, money, rights or possessions. Or intangible – such as respect or authority.

Collaborative peacemaking

The people most directly involved in a conflict or dispute should be able to take part in the peacemaking process. The more involved parties are, the more likely the outcome will succeed.

Unfortunately, this does not always happen. Leaders can close ranks and return to top-down decision making.

Promoting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consensus decision making into peacemaking can significantly enhance the success and resilience of outcomes.

In your group, involve everyone in developing policies and procedures that affect them. Involve them in making collective decisions about what a fair process looks like.

Think about who to involve when resolving conflicts so you can reach the best outcome. For example, if a key person – such as a family spokesperson – cannot attend a mediation session, consider whether it’s worth going ahead without them.

The role of healing in peacemaking

Peacemaking often involves addressing internal issues within your organisation, community or nation. In other words, it requires a commitment to healing. There is increasing recognition of the role healing plays in strengthening internal relationships and improving the effectiveness of your governance.

“Healing gives us back to ourselves. Not to hide or fight anymore. But to sit still, calm our minds, listen to the universe and allow our spirits to dance on the wind … [and] drift into our dreamtime. Healing ultimately gives us back to our country. To stand once again in our rightful place, eternal and generational. Healing is not just about recovering what has been lost or repairing what has been broken. It is about embracing our life force to create a new and vibrant fabric that keeps us grounded and connected.”

– Helen Milroy, Palyku woman, 2009.4Helen Milroy, quoted in Tamara Mackean, Tamara, “A healed and healthy country: understanding healing for Indigenous Australians,” Medical Journal of Australia 190, no 10 (2009): 522-523.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples endured extraordinary suffering because of settler colonialism. Intergenerational trauma marks the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to this day. Further trauma and suffering is realised through ongoing discrimination, poverty, lack of education, poor health outcomes, and disproportionate incarceration – to name only a few.5Jane McKendrick, Robert Brooks, Jeffrey Hudson, Marjorie Thorpe and Pamela Bennett, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Programs A Literature Review, (The Healing Foundation, 2017), 11, [link] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were also prohibited from practising their culture and performing their traditional spiritual healing practices. Some of this knowledge is now lost.

Policies, structures and practices put in place by settler society have also caused disunity, dispute and conflict among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These trauma-based divisions can make it difficult for individuals and groups to work together.

In recent times, there has been significant focus on the importance of healing internal relationships for effective governance.6 Australian Human Rights Commission, Social Justice and Native Title Report 2014, (Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission, 2015), [link]; Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 339-344.

Acknowledging the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups is a critical first step to healing relationships. This includes the trauma and the ways it’s transferred across generations. Groups with ongoing and unresolved trauma are finding they must first start a journey of healing before they come together to decide how they want to govern. Rebuilding and renewing relationships – as part of this healing process – can help equip groups with the tools to come together and govern effectively.7Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 352-353.

The Healing portal is designed to encourage information sharing across sectors. It brings together best practice healing initiatives and information about why healing is needed, and what is working in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander communities. The portal includes the latest research, reports, case studies, videos and tools from around Australia to enable people to bring trauma aware, healing informed practices into their organisations and communities.

The need for healing is expressed at various levels – from individuals to families, to communities and nationwide. It involves healing long-standing disputes and having difficult conversations in a culturally safe space. These approaches are ways to strengthen and build resilient relationships between families.8Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 352-353.

In this sense, healing describes the journey of recovery – and transformation – for First Nations people and groups that have suffered and continue to suffer the effects of settler colonialism.9Linda Archibald, Decolonization and healing: Indigenous experiences in the United States, New Zealand, Australia and Greenland (Ottawa, Ontario: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006), quoted in Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 341.

Healing is an ongoing journey that should be customised for each group. However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can embed healing into their governing structures, future planning and vision. This means – as Euahlayi man Bhiamie Williamson explains – that ‘Indigenous governing institutions become bodies that require as well as promote the ongoing healing of Indigenous communities’.10Bhiamie Williamson, “Healing, Decolonisation and Governance,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 350.

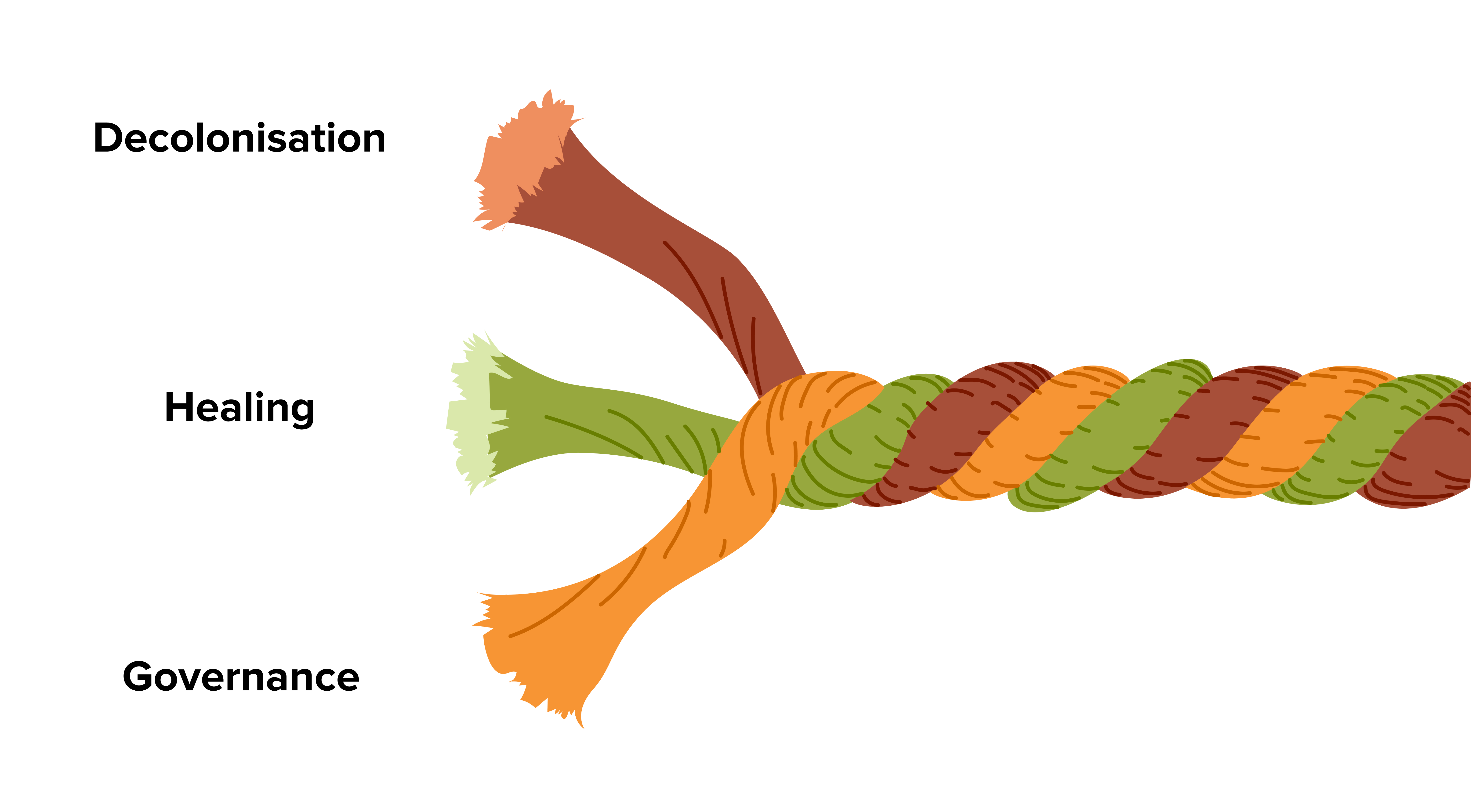

Healing is not a stand-alone process. It’s interconnected with decolonisation and governance. In this sense, decolonisation is a process of recovery and reclamation, and governance is a process of coming together in a culturally informed way. Bhiamie Williamson describes decolonisation, healing and governance as 3 strands. When these strands are woven together, they create strong organisations, communities and nations.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should be aware that this video may contain images and voices of persons who have passed.

In this video, Donna Murray, Wiradjuri and Wonnarua woman and CEO of Indigenous Allied Health Australia, talks about the importance of healing for individuals, community and kinship relations.

Healing internal relationships requires Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to plan strategically and have the resources to partake in a long-term journey.

Use the following checklist to think about the process of healing and where your group is at. Mark where you think you are on the scale, from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The statements you agree with are your areas of strength. You should also consider the statements you disagree with. This will give you an indication of where you may need to focus.

Keep in mind that healing won’t look the same for every group, and people will be at different stages of their healing journey.

These check-ups are intended for self-directed assessment. They can be used by leaders, board directors, or group members who want to evaluate the governance and leadership of their organisation, community or nation. You can do the check-up on your own or as a group and then compare results.

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

View all resources about Conflict resolution and peacemaking

Stay connected

Subscribe to AIGI news and updates.

.png)