To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Nation building, treaty and development

In this topic, we explore nation building, treaty and development. We look at how these concepts link to one another, and to the goal of self-determination.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- Why is nation building important for self-determination? What do you see as being the main benefits of nation building for your group?

- What are the seven core principles of nation building in Australia?

- How can treaty be used as a tool for self-determined governance?

- What kinds of self-determined development are happening in your group? What development do you want to see more of?

Nation building

The Native Nations Institute defines nation building as the processes by which an Indigenous nation enhances its own capacity for effective self-governance, and self-determined community and economic development.1Miriam Jorgensen, “Editor’s Introduction”, in Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development, ed. Miriam Jorgensen (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007), xii. The concept of nation building explores some of the complex challenges involved in exercising self-determination.

Nation building is sometimes referred to as nation rebuilding.2Oren Lyons, “Foreword”, in Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development, ed. Miriam Jorgensen (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007), viii. The word (re)building emphasises that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups were nations before settler colonisation. Colonisation had violent impacts on First Nations – including dispersing families from their lands, removing children from parents, and suppressing language and ceremony. Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are rebuilding their collective nationhood in ways that both:

- have cultural depth and credibility for them

- make use of the best tools and tactics of the modern realities in which they live.

Nation building is about how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can come together after the trauma of colonisation. How they create the tools they need to build the futures that they want – and put them into place. By tools, we mean the rules, processes, checks and balances, and structures of governance. Because Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations are diverse, the forms of nation building each group takes will be similarly diverse.

“When I think about nation building, to me it encompasses a range of different things, but mostly it’s about empowering and organising our people in a way that allows us to define our own destinies, to be in positions of decision-making and to set up our own government structures that support our own cultural foundations as a nation or as a community or tribal group but also how we actually put ourselves in a position to invest in our futures; you know, void of government intervention or void of the kind of parameters that we’re so used to that have applied in Indigenous affairs in a lot of ways throughout history.”

– Michelle Deshong, Kuka Yulanji woman, Leading Native Nations, 2016.3Michelle Deshong, “Australian Aboriginal Methods of Self-Governance,” Leading Native Nations, Native Nations Institute, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, April 19, 2016, video, 1:16, [link]

There are many different views and understandings about what a nation is and what it means to be part of a nation.

Today, the concept of ‘nation’ is part of an ongoing and widespread discussion that encompasses First Nations peoples across the world. What’s common to these conversations is the central idea of what it means to be a First Nation. It’s about a group of people who have a deep relationship with and connection to their lands and waters, coming together to act as a collective political group with a jurisdiction.4Diane Smith, “Governing for Nation-Building, Thematic Introduction: Concepts, Issues and Trends,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 111. These First Nations have been self-governing for thousands of years before colonisation.

In Australia, the term First Nations is increasingly used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups. Not all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples see it as a reflection of their cultural, political or kin-based arrangements. Some groups prefer using other terms, for instance the name of their ‘mob’, language group, place name or clan group. For other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, First Nations is used as a way to acknowledge the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and reassert their sovereignty.

Importantly, every First Nation in Australia is unique. Some may share a common territory bounded by physical borders. The Yolngu peoples of northeast Arnhem Land, for example, have largely remained on their lands in smaller clan groups. Others may be dispersed across a vaster territory. For example, the Noongar Nation has many people spread across towns, cities and communities in southwestern Australia. Through native title and land claims, they’ve brought this dispersed population together as a Noongar Nation.

Many Australian First Nations have smaller clan or language groups. For example, the five distinct groups within the Kulin Nation – the Wurundjeri, Wathaurong, Boonwurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung and Taunurong peoples – may choose to act as one nation or come together as smaller nations.

The Ngarrindjeri Nation consists of eighteen tribes. Although each tribe has its own defined territory, the nation has a formal governing council, the Tendi, and more recently a peak body known as the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA). The NRA board comprises members of key Ngarrindjeri community organisations, bodies and committees (including the Tendi), as well as some elected community members.3Steve Hemming, Daryle Rigney and Shaun Berg, “Ngarrindjeri Nation Building: Securing a Future as Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar (Lands, Waters, and All Living Things),” in Reclaiming Indigenous Governance: Reflections and Insights from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, eds. William Nikolakis, Stephen Cornell and Harry Nelson (Tucson: University of Arizona Press,2019), 82.

Ngarrindjeri flag, designed by Matt Rigney.

In 1999, the Ngarrindjeri Nation of the Lower River Murray, Lakes and Coorong first flew this flag as part of a proclamation to reclaim rights over their lands.

“The 18 dots represent the 18 Laklinyeris (tribes) that make up the Ngarrindjeri Nation. The spears represent the traditional fishing spears of the Ngarrindjeri. The boomerang is the Sacred Boomerang that, when thrown, circles the Laklinyeris, informing their clan leaders to attend a Nation Meeting called Tendi (which makes and interprets Ngarrindjeri Law). The blue represents the waters of Ngarrindjeri Country. The sun gives life. The ochre colour of the boomerang represents our mother — Mother Earth.”4Ngarrindjeri Nation and Steve Hemming, “Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri Country and Culture: Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan (Listen to Ngarrindjeri People Talking),” in Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth Region (Yarluwar-Ruwe), eds. Luke Mosley, Qifeng Ye, Scoresby Shepherd, Steve Hemming and Rob Fitzpatrick (Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, 2018), 5.

Governance for nation building

Governance for nation building refers to the practical ways that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples get done the things that matter to them.

Simply put, it’s how they govern in a way that maximises their ongoing self-determination.

Governance for nation building is distinct from organisational or corporate governance. Organisational governance may be an element of nation building, and many First Nations are represented by corporations governed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However, nation governance and corporate governance are different.

Organisations, particularly incorporated groups, may be accountable to external governments or funders in addition to their community. Interactions with state or federal governments are viewed as government-to-organisation.

Governance for nation building, on the other hand, sees the nation accountable to its members. Unlike corporations, the aim is that interactions are viewed as government-to-government or nation-to-nation.5Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), 24, [link]

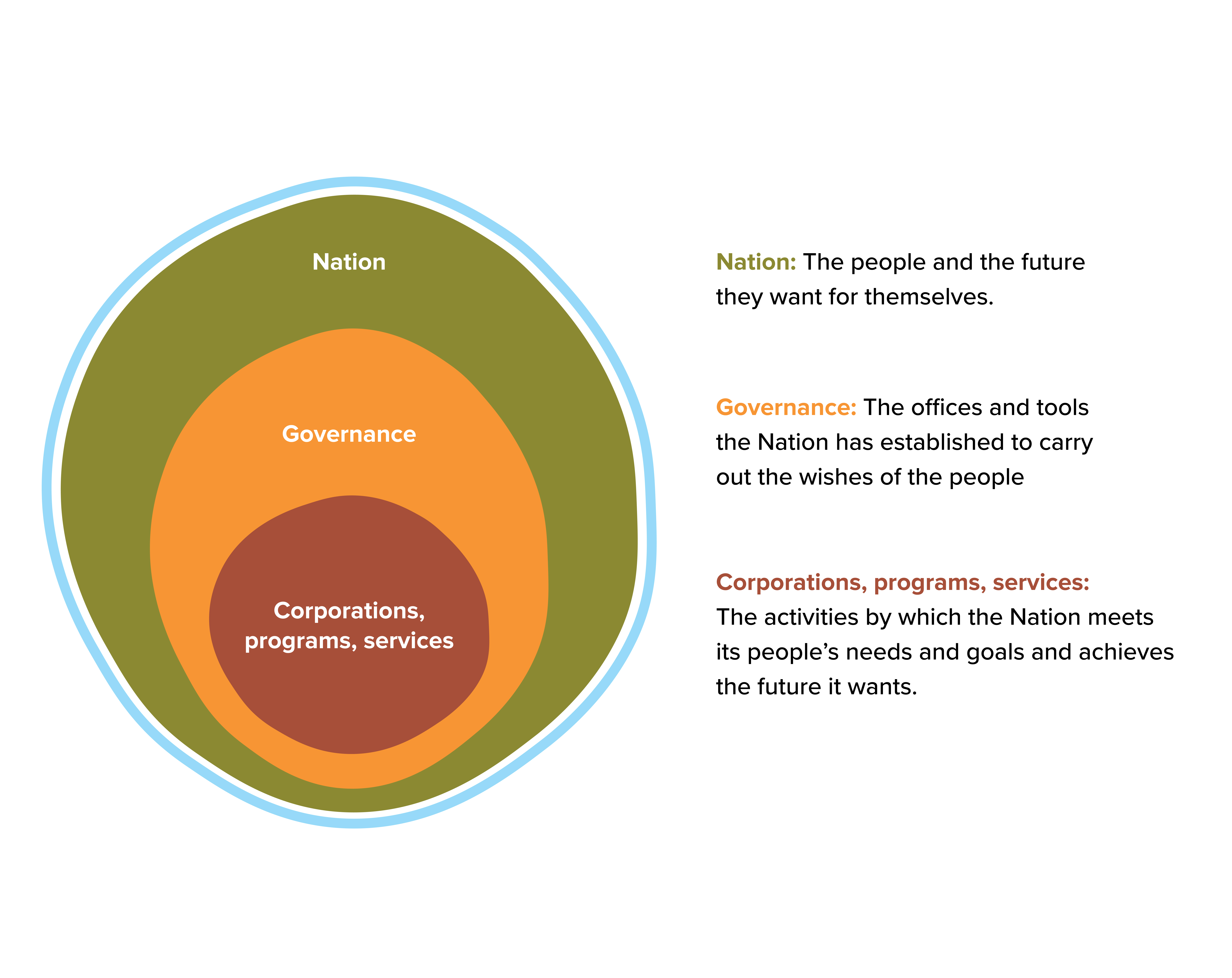

Miriam Jorgensen, Research Director of the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona, suggests looking at governance for nation building as part of a three-piece ‘puzzle’:6Miriam Jorgensen, cited in Toni Bauman, Diane Smith, Robynne Quiggin, Christiane Keller and Lara Drieberg, Building Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance: report of a survey and forum to map current and future research and practical resource needs (Canberra: AIATSIS and the Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2015), 44-47, [link]

- Coming together as a nation is the first piece of the puzzle. It’s about identifying as a collective group who share a vision for their future and the future of their children.

- The second piece is governance. A nation must organise as a polity or a community with a collective political identity. It must have effective governing institutions and mechanisms to get things done – in a way that corresponds to the culture and values of the group. In other words, the nation’s governing bodies must be culturally legitimate.

- The third piece is what Jorgensen refers to as the ‘capacity’ of nations to achieve desired outcomes and collective goals. This may include formal and informal nation building activities. For example, service delivery (like mental health services or the management of natural resources) carried out by nation members as part of the nation building project.

– Diagram adapted from Miriam Jorgensen, University of Arizona and University of Melbourne, Distinguishing Indigenous nation, Indigenous governance and Indigenous governing capacity, 2015.2Miriam Jorgensen, cited in Toni Bauman, Diane Smith, Robynne Quiggin, Christiane Keller and Lara Drieberg, Building Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander governance: report of a survey and forum to map current and future research and practical resource needs (Canberra: AIATSIS and the Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2015), 46, [link]

“Nation building sees a shift in focus from the community organisation to the community; from a service delivery population to community members and from accountability to external funders or non-Indigenous governments to the community. This approach sees community organisations as tools of the community, used to facilitate community identified goals.”

– Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper, 2022.7Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), 23-24, [link]

Core principles of nation building in Australia

The Native Nations Institute points to five principles that are particularly important for nation building or rebuilding.8“What Is Native Nation Building,” Native Nations Institute, accessed 2022, [link] We have identified two additional elements that reflect nation building for First Nations in the Australian context:

- nation solidarity

- organising as a nation.

Keep these principles in mind when deciding how you will get started on the practical work of governance for nation building in the following topic.

Sovereignty

The nation makes the major decisions.

First Nations that have been willing and able to assert self-governing power have significantly increased their chances of sustainable economic, cultural, social and community development.

Nation solidarity

The nation rebuilds trust and unity to work together as one.

This acknowledges that past trauma, divisions and imposed arrangements may have kept members of the nation apart. Nations that take steps to rebuild their internal relationships in ways they value can work collectively and in solidarity.

Organise as a nation

There’s an understanding of where to start and what needs to be done to meet future goals and aspirations.

Nations that can identify a starting point and create a shared vision can build themselves into more effective nations.9Jody Wilson-Raybould and Time Raybould, Governance Toolkit: A Guide to Nation Building, The Governance Report (Vancouver: British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, 2014), section 2.2, [link]; Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian and Steve Hemming, Indigenous Nation Building and the Political Determinants of Health and Wellbeing Discussion Paper (Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2022), 21-22, [link] This is about understanding that the nation building journey is long-term and the initial work is essential. To be successful, nations must have a clear idea of what will help them build strong foundations.

Capable governing institutions

We define institutions as the systems, rules, strategies and standards a nation uses to govern itself.

Capable governing institutions means the nation backs up authority with competence.

The chances of sustainable development rise as First Nations put in place effective, non-politicised dispute-resolution mechanisms and build capable bureaucracies.

Cultural legitimacy and credibility

Governing institutions match community beliefs about how authority should be organised.

Institutions that build and innovate upon Indigenous conceptions of governing responsibilities have a better chance for nation building.

Strategic future orientation

Decisions are made with long-term priorities in mind.

Successful First Nations tend to approach development not as a quick fix for disadvantage, but as a means of building a society that works.

Nation-spirited leadership

People who recognise the need for fundamental change and can engage with community to make that happen.

In successful nations, there’s usually a group of people who recognise the need for fundamental change in the way things are done. They can bring the community along with them in building that future. This is self-determination for the collective, not selfish determination for a few.

Nation building approaches

While every nation will follow its own path, there are often similarities in the work of nation building. One is ‘looking inwards’ and refocusing on internal matters. This includes considering:

- who makes up your collective identity

- how you define or understand that identity

- how you make sure the voice of every member is heard

- the role of culture in your nation’s governance

- how to build or (re)build your internal relationships.

What worked to get people through times of political advocacy or hard legal negotiations with colonial governments may not work to implement the rights and benefits secured from those actions.

In Australia, governance arrangements have often been imposed on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups from the outside. Decisions have been imposed according to the agenda, priorities and values of mainstream governments, missionary churches and others. A nation building approach makes sure other people aren’t making decisions for you.

While effective nation building should be customised to suit the needs and situation of your group, a nation building approach to governance will often have certain shared characteristics:

- culture is seen as a strength and asset

- decision-making is longer-term, strategic and under the control of the nation

- future agenda-setting is directed by the nation

- development is seen as an interrelated social, economic and cultural goal

- leaders act as nation-builders, mediators and motivators, and make decisions based on plans

- accountability is to the nation’s members and focuses on collective goals

- governing rules and frameworks reflect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander political cultures and concepts.

The result of taking a nation building approach to governance is:

- growing governance capacity

- consensus decision-making

- sustainable enterprises and community development

- a governance culture where risk is evaluated, managed and diversified

- an impression of competence and resilience

- socioeconomic progress.

– Adapted from Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt, Two approaches to the development of native nations, 2007.10Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt, “Two approaches to the development of native nations,” in Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development, ed. Miriam Jorgensen (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007).

Your group may already be practising nation building, even if you don’t refer to it as that. Examples of acting as a nation are:

- managing native title claims

- running cultural camps

- negotiating with state or federal governments on issues like caring for Country, land and water management

- working with researchers and your community on repatriation.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should be aware that this video may contain images and voices of persons who have passed.

The way nation building happens in Australia is very different to nation building in the United States, Canada and New Zealand.

Daryle Rigney, a citizen of the Ngarrindjeri Nation and Director of the Indigenous Nations and Collaborative Futures Research Hub, speaks about nation building in Australia and how it differs from nation building in international contexts.2Honoring Nations, “What does nation building look like in Australia compared to the US or Canada? Daryle Rigney,” June 1, 2019, from the Next Horizon: A Symposium on the Future of Indigenous Nation Building, 1:58, [link]

Treaty

Over past decades, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have won certain legal and political rights and recognition. How can this be translated into genuine self-determination and self-governance? This is a question many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are facing.

In Australia and overseas, many First Nations are using treaty negotiations as an opportunity to advance their self-determination and sovereignty. A treaty is a settlement or agreement arrived at by negotiation, which gives rise to binding obligations between two ‘sovereign entities’ (usually states, nations or governments).11Daryle Rigney et al., “Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 123. It’s an agreement between two parties who want their relationship with each other spelt out.12Michael Dodson, “What is a treaty?,” in What Good Condition: Reflections on an Australian Aboriginal Treaty 1986-2006, eds. Peter Read, Gary Meyers and Bob Reece (Canberra: ANU Press, 2006), 106.

“We can’t possibly hope to negotiate a treaty or any other form of meaningful national agreement if we don’t have governance structures that legitimise our side of the negotiation.”

– Jackie Huggins, 10th Annual Cultural Heritage and Native Title Conference, Brisbane, September 30, 2003.

In Australia, calls for treaty generally refers to the desire for an agreement between First Nations and the nation-state of Australia (acting through the federal, state and local governments). This treaty would recognise the sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

First Nations existed before white settlement. They don’t rely on legislated rights or treaty recognition from the nation-state of Australia for their internal cultural legitimacy – although today, rights and recognition can strengthen a nation’s self-determination and decision-making powers.13Diane Smith, “Governing for Nation-Building, Thematic Introduction: Concepts, Issues and Trends,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 110-111. How and whether First Nations peoples seek recognition is for those First Nations to decide.14Alison Vivian et al., “Indigenous Self-Government in the Australian Federation,” Australian Indigenous Law Review 20, (2017): 218.

When a First Nations group decides to collectively enter a treaty negotiation (whether with a nation state or another First Nation) it is a sovereign decision: they’re acting as a sovereign, in a self-determined way.

Because treaties often refer to substantial matters such as rights, lands, water resources and entitlements – which may be exchanged or shared – the conditions of a treaty need to be well governed. This is to ensure commitments are delivered and properly implemented.

“Treaties are foundational constitutional agreements between First Nations and the state that involve a redistribution of political power. Treaties are agreements aimed at settling fundamental grievances, and establishing binding frameworks of future engagement and dispute resolution. Treaties are legal frameworks, so there will be disputes over interpretation. Treaties are not blank canvases on which governments and overbearing bureaucrats can present the status quo.”

– Megan Davis, Professor of Law and Cobble Cobble woman, 2019.15Megan Davis, quoted in Tony Dreise, Are we mates yet? Agreement making between States and First Nations (NSW: Aboriginal Affairs New South Wales, 2019), 6.

The purpose of treaty

There are no rules around what a treaty can call for. Throughout history, they’ve been used to negotiate peace, end conflict, establish diplomatic relations, divide territories and recognise or accept sovereignty.

Treaty negotiations can focus on establishing an agreed framework through which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and federal, state or local governments interact in the future. In addition, the purpose of a treaty may be to formally:

- afford legal and Constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ rights

- acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first and sovereign nations of Australia

- offer repatriation for the dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ lands and waterways

- settle historical conflicts, recognise past wrongs and make an apology for those wrongs

- exchange land rights for financial and other benefits

- give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples the authority to be self-governing

- enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to have control over decisions that impact their own affairs.16Tony Dreise, Are we mates yet? Agreement making between States and First Nations (NSW: Aboriginal Affairs New South Wales, 2019), 27.

Through the above, treaties can encourage greater development, improved well-being and self-determination.

In settler-colonial states, treaties are usually associated with agreements between Indigenous groups and settler governments. However, treaties between First Nations peoples have long been a form of governance and diplomacy. Treaties are not a new concept for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

First Nations peoples had treaties with each other well before present-day treaty negotiations. These treaties were based on Indigenous values, concepts and governance principles. They’re now used (or have the potential to be used) as the basis for contemporary treaty negotiations with Australian federal, state or local governments. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples prefer to use their own treaty principles as the framework for negotiations, rather than non-Indigenous frameworks.

“For Ngarrindjeri, any treaty worthy of the name must act as a tool for the renegotiation of jurisdiction and the powers of Indigenous self-governance. In other words, treaty must enable and support the sovereign activities of the Aboriginal people party to the agreement, and should encourage the future flourishing of their Indigenous nationhood as the fullest expression of the developmental potential contained in the principle of Aboriginal self-determination. Anything less would simply diminish the solemnity of and significance inherent in a genuine treaty agreement, and Ngarrindjeri would rather walk away from the negotiations.”

– Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian, Steve Hemming, Shaun Berg and Damein Bell, Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building, 2021.17Daryle Rigney et al., “Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 130.

Not all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples agree on the potential benefits of treaties in Australia. Some are dissatisfied with the lack of substantive outcomes from current treaty negotiations, as well as the lack of a clear consensus model. For others, there are fears that treaty may undermine, or put at risk, the question of sovereignty.18Bhiamie Williamson, “Treaty: All Ship, No Cargo,” Arena Online, June 3, 2021, [link]

Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian, Steve Hemming, Shaun Berg and Damein Bell explain the role of treaty in Ngarrindjeri nation rebuilding, and how treaty discussions helped support and guide their nation rebuilding journey.2Daryle Rigney et al., “Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 135.

“For Ngarrindjeri, their participation in treaty discussions, though aborted before an agreement could be reached, at the same time provided valuable political knowledge transferrable to their wider project of sovereign nation-rebuilding. Among other things, their engagement in treaty discussions confirmed some key practice-related lessons of Indigenous nationhood.

First, develop and hold your political ground in an appropriately sovereign way; begin by establishing authority in the process itself as a primary sovereign act of political relationship and don’t let the state control the relationship, or decide the nature of the process, or determine the limits of the outcomes.

Second, keep your organisation disciplined and maintain a firm agenda; plan strategically for the unplanned; know your teams’ individual and overall capacities, such as who has the right skills to achieve the desired outcomes; know how to delegate responsibility while maintaining control.

Third, remain mindful of the desired end point and know what cannot be left out or negotiated away; know in advance when to compromise, and why – for what gain?

Each of these involves the exercise of sovereign decision-making for the strategic purpose of advancing the Nation’s long-term interests. For this reason, we suggest nation-rebuilding is a necessary supportive framework for Indigenous peoples involved in treaty and, at the same time, that treaty can be a useful tool for advancing Indigenous nationhood.”

Treaty progress in Australia

Article 37 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that:

“Indigenous peoples have the right to the recognition, observance and enforcement of treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements concluded with States or their successors and to have States honour and respect such treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements.”

Nation-states such as the United States, Canada and New Zealand have entered into treaties with First Nations peoples. This has not happened in Australia to date.19Michael Dodson, “What is a treaty?,” in What Good Condition: Reflections on an Australian Aboriginal Treaty 1986-2006, eds. Peter Read, Gary Meyers and Bob Reece (Canberra: ANU Press, 2006), 106.

There have been many calls for treaty negotiations in Australia. Most recently, in May 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates gathered in Central Australia and presented the Uluru Statement from the Heart. The Uluru Statement calls for structural reforms, summarised as ‘Voice, Treaty, and Truth’.

Various First Nations groups across Australia have entered treaty negotiations with state and territory governments. While these negotiations have seen varying levels of success, First Nations groups have consistently demonstrated innovation, adaptability, resilience and self-determination in the governing of both past and ongoing treaty processes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups have employed customised and adaptive strategies to navigate, resist, and strategically engage with settler-colonial systems and policies to advance their goals of self-governance and self-determination. Many are also repurposing the native title system beyond its original settler-colonial design to support nation-building and self-determined development. Some nations have and continue to leverage the native title system to advance their treaty efforts. As Anthea Compton, Alison Vivian, Theresa Petray, Matthew Walsh and Steve Hemming recognise, settler governments continue to prefer engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through familiar, established bodies.20Anthea Compton, Alison Vivian, Theresa Petray, Matthew Walsh and Steve

Hemming, “Indigenous nation building and native title: strategic uses of a fraught settler-colonial

regime,” Settler Colonial Studies 14, no. 2 (2024): 171, DOI: 10.1080/2201473X.2023.2267409. Native title bodies have played a key role in these discussions, with treaty negotiations across several states and territories in Australia centring around interactions with these organised, representative First Nations groups.21Anthea Compton, Alison Vivian, Theresa Petray, Matthew Walsh and Steve

Hemming, “Indigenous nation building and native title: strategic uses of a fraught settler-colonial

regime,” Settler Colonial Studies 14, no. 2 (2024): 171, DOI: 10.1080/2201473X.2023.2267409.

Other strategies employed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups include the creation of truth-telling commissions, advisory groups, treaty units, independent representative bodies, as well as Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) and agreements between governance agencies and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These varied approaches highlight that there is no single formula for governing treaty processes or achieving self-determination.

Although not all treaty processes are advancing equally across states and territories, valuable lessons can still be drawn from these efforts. Building the capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups to govern treaty processes is an important element of self-determination, and these ongoing initiatives offer insights into how self-determined governance and treaty negotiations can unfold in diverse and innovative ways.

“Rather than beginning with treaties to secure ‘rights’ from the settler nation-state, Ngarrindjeri have developed transformational technologies that assert sovereignty, extend and establish jurisdiction, and develop governance as a pathway to securing rights.”

– Steve Hemming, Daryle Rigney and Shaun Berg, Ngarrindjeri Nation Building: Securing a Future as Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar (Lands, Waters, and All Living Things), 2019.22Steve Hemming, Daryle Rigney and Shaun Berg, “Ngarrindjeri Nation Building: Securing a Future as Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar (Lands, Waters, and All Living Things),” in Reclaiming Indigenous Governance: Reflections and Insights from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, eds. William Nikolakis, Stephen Cornell and Harry Nelson (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2019), 76.

Treaties offer a formal acknowledgment of the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to govern themselves. A treaty can be an important tool to help build a nation’s self-governing authority. However, while a treaty can greatly enhance its jurisdictional and decision-making power, First Nations should not rely on legislated or treaty recognition. Creating a governance model that reflects the nation, its goals and aspirations is possible regardless of a treaty.

A treaty is not an end in itself. It’s an opportunity to focus on the bigger picture: community members working together to rebuild their internal relationships and reclaim their self-determined ways of governing.

In Victoria, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have governed their treaty process through the First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria. The assembly is an independent and democratically elected body that represents Traditional Owners of Country and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the state.

The Assembly established key structures to support the treaty process, including a Treaty Authority (an independent body that oversees treaty-making in Victoria), Self-Determination Fund, Treaty Negotiation Framework and a dispute resolution process.

A core principle guiding the Assembly’s work in treaty negotiations is that decisions affecting Aboriginal communities, cultures, and lands should be made by Aboriginal peoples themselves. This is self-determination in action.

Truth-telling was also recognised as an important component of the governance and ongoing treaty discussions. In consultation with Aboriginal peoples throughout the state, the Yoorrook Justice Commission was established to investigate injustice against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Victoria since colonisation.

For more information on the treaty process in Victoria visit the First Peoples – State Relations website or the First Peoples’ Assembly.

In the Northern Territory, treaty discussions were guided by a Memorandum of Understanding (known as the Barunga Agreement) between the NT government and the territory’s four Aboriginal land councils: the Northern Land Council (NLC), the Central Land Council (CLC), the Tiwi Land Council (TLC), and the Anindilyakwa Land Council (ALC). These land councils represent the interests of Aboriginal peoples within their respective regions.

Recognising the diversity in interests across Aboriginal communities was an important aspect of the Barunga Agreement, as was the acknowledgment that all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the NT should have the opportunity to engage meaningfully in the process through their representative bodies.

The Barunga Agreement followed a longer history of efforts towards self-determination in the NT. In 1988, the Barunga Statement was presented to then-Prime Minister Bob Hawke. This statement called for self-determination, compensation for loss of land, freedom from discrimination and respect for Aboriginal identity, and the recognition of Aboriginal social, economic, and cultural rights.1AIATSIS, “The Barunga Statement,” accessed January 2025, https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/barunga-statement; Rona Glynn-McDonald, “The Barunga Statement and Agreement,” Common Ground, updated October 31, 2022, [link].

Read the Barunga Agreement. Further information can be found at Aboriginal Affairs.

Community consultation played an important role in treaty discussions in Tasmania. An independent report, Pathway to Truth-Telling and Treaty, was developed following extensive consultation with Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals and communities. Over 100 meetings were held, including several via videoconference with individuals living on the Australian mainland and abroad.2Kate Warner, Tim McCormack and Fauve Kurnadi, Pathway to Truth-Telling and Treaty: Report to Premier Peter Gutwein (Hobart: Department of Premier and Cabinet, 2021), 24. These discussions led to twenty-four recommendations determined by Tasmanian Aboriginal people themselves.

An Aboriginal Advisory Group was also established to deliver strategic, culturally informed advice to guide decisions and policy related to the process of truth-telling and treaty with Tasmanian Aboriginal people. The advisory group’s membership was based on nominations from the Aboriginal community.3Kate Warner, Tim McCormack and Fauve Kurnadi, Pathway to Truth-Telling and Treaty: Report to Premier Peter Gutwein (Hobart: Department of Premier and Cabinet, 2021).

Find information and communiques from the Aboriginal Advisory Group’s meetings.

In Queensland, a Treaty Advancement Committee undertook consultations to gauge community support for the treaty process. The committee proposed a two-stage approach to truth-telling and healing, which included local truth-telling and healing initiatives in collaboration with public institutions.4“Path to Treaty,” Department of Women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships and Multiculturalism, last updated 2 December, 2024, [link].

The committee also recommended the creation of a legislated First Nations Treaty Institute, a Truth-telling and Healing Inquiry, and an Independent Interim Body (IIB) to oversee the treaty process in Queensland. The IIB would be composed of both First Nations leaders and non-Indigenous representatives, ensuring that decision-making was guided by those directly affected by the treaty process.

Read key documents related to Queensland’s treaty discussions.

Although Western Australia has not committed to a treaty process, native title settlement agreements in the state have incorporated key elements typical of treaty negotiations. In 2015, an agreement known as the South West Native Title Settlement, was reached between the Noongar Nation and the Western Australian Government. The Noongar people exchanged native title rights for a settlement package comprising land ownership recognition, heritage rights, access rights and a ‘future fund’ trust, among other benefits. Some academics consider the South West Native Title Settlement to be Australia’s first treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.5Harry Hobbs and George Williams, “The Noongar Settlement: Australia’s First Treaty,” Sydney Law Review 1, (2018): 40, [link].

In South Australia, treaty negotiations took place between the state government and Aboriginal nations acting as sovereign groups.

Three Aboriginal nations – the Narungga Nation, the Adnyamathanha Nation, and the Ngarrindjeri Nation – entered into treaty negotiations with the South Australian Government. This marked a clear assertion of their sovereign authority, with each nation exercising their right to self-determination to pursue long-term goals and interests. An Aboriginal Treaty Advisory Committee played a key role in this process, recommending the inclusion of these nations in treaty discussions.

Consultation was also an important aspect of treaty negotiations in SA. A First Nations Treaty Commissioner engaged with over 600 Aboriginal people across the state and received more than 280 written submissions.6ANTAR, “Treaty in SA,” lasted updated 17 September, 2024, [link].

One significant outcome was the Buthera Agreement, signed between the Narungga Nation Aboriginal Corporation and the South Australian Government. The agreement included capacity-building support for the Narungga Nation Aboriginal Corporation to sustain effective governance arrangements, drive economic development and protect Narungaa culture and language.7Narungga Nation Aboriginal Corporation (NNAC) and the State of South Australia (the State), Buthera Agreement, Guuranda (Yorke Peninsula), 16 February 2018, [link]. Part of the agreement contained an intent for the parties to promote “a legislative structure that enables the parties to negotiate entry into a treaty in the future”.8Narungga Nation Aboriginal Corporation (NNAC) and the State of South Australia (the State), Buthera Agreement, Guuranda (Yorke Peninsula), 16 February 2018, [link].

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority, on behalf of the Ngarrindjeri Nation, and the South Australian state government also entered into treaty discussions. The Ngarrindjeri Nation held treaty forums to allow all Ngarrindjeri to have a say.9Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority, “Ngarrindjeri Treaty Update,” accessed January 2024, [link].

Read the Buthera Agreement.

In the ACT, it was recognised that engaging in meaningful conversations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples about what treaty means in the territory, and how the treaty process could unfold, was an important first step in the journey toward treaty negotiations.

It was also acknowledged that conversation and acknowledgment of all relevant First Nations groups in the ACT would be key for successful treaty discussions.

Read more about the ACT treaty process.

In NSW, a consultation process with First Nations peoples across the state was recognised as an important first step in treaty.

The purpose of these consultations is to listen to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander views on treaty or other formal agreements and to explore what form this could take. The consultation process is led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, acknowledging their right to determine their own stance on a treaty.10NSW Government, “Consulting Aboriginal people on desire for a treaty process,” accessed February 2025, [link].

Consultations are independent and inclusive, with three First Nations Treaty Commissioners appointed to design and lead the discussions. The Commissioners aim to ensure all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in NSW have the opportunity to engage with the consultation process covering metropolitan, rural, regional, and remote areas.

Development

Development is change or transformation that makes life better in ways that people want. It’s about empowering people to achieve the community, social, cultural, political and economic benefits they desire, and to maintain them over the long term.

As stated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), ‘Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.’23UN General Assembly, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295, [link]

What this means is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have the right to decide what forms of development they desire, and how to implement them. This includes deciding:

- what development and sustainable development mean for them, in practice

- their development priorities and objectives

- who will benefit from the development

- how development happens, including how they will govern development to reach desired outcomes.

Being in control of these decisions is what self-determined development is all about.

Development takes different forms – from community and economic development to social, cultural or political development.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups focus on holistic development. Holistic development may include social, community and economic development, as well as the political, spiritual, emotional and mental development of individuals, families or nations. It’s about enabling communities to be healthier and stronger in more ways than one.

Often, community development is prioritised over economic development. Community development means addressing community needs, drawing on community resources and harnessing opportunities for sustainable outcomes. With self-determined community development:

- power is handed back to the community or group

- community members lead programs or development strategies

- knowledge and expertise of community members are centered

- outcomes are long-term.24“What is community development?” Australian Institute of Family Studies, updated October 2019, [link]

“I strongly believe the principles of social justice and the right to self-determination must ground any initiatives in order to succeed. The heart of self-determination for First Nations Peoples is having the power to make those decisions that mostly affect their daily lives. I also believe that we must learn from organisations that have successfully delivered community development initiatives in the past.”

– Patricia Anderson AO, Alyawarre woman and Chair of the Lowitja Institute and Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, 2020.25Community First Development, A First Nations’ Approach to Community Development: Our Community Development Framework (Community First Development, 2020), [link]

While a community development approach may be the first step for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations, improving economic well-being remains important. Economic development driven by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations is key for economic empowerment and independence. It can take a variety of forms, including:

- growth in traditional subsistence activities

- increased participation in market economies

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander entrepreneurship

- joint ventures with non-Indigenous corporations

- collective nation, community and clan enterprises

- small individual and family cottage industries (businesses or enterprises carried out from people’s homes).

Governing for sustained development

Enhancing your group’s capacity for sustained, self-determined development means having strong governance in place.

Taking a nation-building approach to governance is one way to drive capacity for sustained development. This can be community, economic, social, political or cultural development. According to Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt, a nation-building approach to sustained development:

- is about being proactive

- responds to an agenda (from strategic planning for the long-term future)

- emphasises an environment in which businesses can last

- measures success by considering social, cultural, political, and economic impacts

- views development as the job of nation and community leadership

- treats development as a political problem (rather than an economic problem)

- sees the solution as creating sound institutional foundations, strategic direction and informed action (rather than securing grants or following other economic endeavours).26Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt, “Sovereignty and Nation-Building: The Development Challenge in Indian Country Today,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 22, no 3 (1998): 194, [link].

Regardless of what your desired outcomes are, taking a nation-building approach is likely to drive sustainable development. Development is sustainable when it ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.27World Commission on Environment and Development and UN Secretary-General, Our Common Future (United Nations: New York, 1987), 24, [link]

As such, it requires groups to carefully consider their preferred direction of development, and the speed at which change will be sustainable into the future.

All types of development can have profound and transformative effects on the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations. It’s important that there are strong, culturally-led governing institutions in place to support it.28Janet Hunt and Toni Bauman, No more business as usual: The need for participatory Indigenous development policy and skilled practice, Policy Insights Paper No. 06/2022 (Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, [link]

Evidence from national and international research indicates that having effective and legitimate governance is a ‘development enabler’. For instance, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) suggests that the capacity for governance is at the heart of sustainable human development and a prerequisite for effective responses to the kind of poverty, unemployment, early mortality, reliance on welfare transfers and environmental and gender concerns which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples face.29United Nations Development Program, Capacity development: A UNDP primer (United Nations Development Program: New York, 2009), 13, [link]

In other words, it pays to invest in your governance.

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the internal ‘test’ of sustainability in development initiatives involves considering:

- what kind of future you’re trying to build, not only for yourselves but for the next generations

- the kinds of governance arrangements that might be acceptable and consented to now, and will remain acceptable to your people in the future

- the role your collective culture will play in your governance arrangements and economic initiatives, and how this might change over time

- who should benefit from economic development, and whether the benefits of current development will still be available for future generations

- the kinds of development that will help you maximise self-determination in the long run.

Effective governance enables a nation to properly consider the above, and prioritise, plan and implement solutions.

While important, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups do not need legislated rights or treaties for sustainable development. However, having governance arrangements that put self-determination into successful practice, and fully engage members in considering options for the future, is critical.

In July 2012, UN Member States reaffirmed good governance as a foundation for development:

“… good governance and the rule of law at the national and international levels, as well as an enabling environment, are essential for sustainable development including sustained and inclusive economic growth, social development, environmental protection and the eradication of poverty and hunger.”

– United Nations General Assembly resolution 66/288.

Governing capabilities needed for development

Extensive research suggests there are important governance capabilities needed to get successful development happening. These include:

- a stable, accountable leadership

- broadly representative and fair representative structures

- strong culture-based rules of governance

- capable management and staff support

- clear lines of authority and responsibility

- consistent and fair decision-making

- fair and reliable dispute resolution processes

- strategic business planning and risk management

- effective communication and information systems

- networks with public or private sector partners to engage with the wider economy

- working infrastructure in place

- education and financial literacy

- access to relevant training and mentoring opportunities

- legitimacy and credibility with your members.

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

Stay connected

Subscribe to AIGI news and updates.

.png)