To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Board of directors

In this topic, we introduce you to the roles and responsibilities of the board of directors. We look at best practices for boards and ways to improve your own board’s effectiveness. We also look at the roles, rights and responsibilities of individual directors.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- What are the main roles of a board of directors?

- What do the terms power and delegation mean?

- What is the composition of your board? Are there sub-committees of the board?

- What are the five legal duties of a director? What are the consequences of breaching these?

Understand your board

A board is a group of people who have the power and authority to form the policy and steer the direction of an organisation, community or nation. A board is also called the ‘governing body’ or ‘board of directors’.

Boards come in all shapes and sizes and have varied functions. Generally, incorporated organisations are required to be managed by a board or governing body that meets at least once a year at an annual general meeting (AGM). In some groups – particularly unincorporated groups – the board can be:

- a council

- a committee

- an assembly of Elders or traditional owners

- a selection of family groups

- clan representatives.

Board directors can be elected by members voting, or be selected through nomination using traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander decision-making processes.

An incorporated organisation’s constitution, rulebook or charter sets out how members can be elected to the board, and the particular governing responsibilities directors have to undertake. Board directors are usually appointed for a specific length of time – often three or four years.

Reasons people are selected or elected to a board include:

- their corporate or industry-specific skills and knowledge

- their cultural authority

- their age, gender or background

- other factors considered important for a position of leadership within the group, such as the communities they serve.

If an organisation has a specific focus on a particular section of society – such as people with disabilities, youth, aged care, LGBTQIASB+ – then it will have directors who have experience in those matters.

The benefit of having board directors with different skills, experience and characteristics means they complement and balance each other. For example, if there are two directors who are business savvy, it may be okay for another director to have less knowledge in that area. They bring a set of different strengths.

It’s the board as a collective unit who make and implement decisions on behalf of the group and its members. No individual board director has that power.

Yappera Children’s Service Co-Operative is governed by a board of seven Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander directors. These directors are elected by Yappera’s membership during the Annual General Meeting (AGM) and serve a two-year term. Upon election, each new director receives a comprehensive induction pack that formally outlines the expectations and responsibilities of their role.

The board meets every six weeks, with additional meetings scheduled as needed – this meeting schedule has proven effective for the board. Yappera’s chairperson also remains actively involved in the organisation, ensuring directors are fully aware of their duties from the outset of each meeting. Meetings are conducted in a manner that values all perspectives, and each director’s opinion is heard and respected.

Many board members have been deeply connected to Yappera in different capacities throughout the organisation’s history – including as parents, previous staff members, grandparents and community members.

Yappera ensures board members bring a diverse range of skills across the health and education sectors, as well as in finance and management operations. The organisation also prioritises gender balance among board members. Historically, Yappera’s board has had a higher proportion of women representation compared to men due to the nature of being an Aboriginal organisation working in the early childhood setting. More recently, however, there has been an increase in male participation on the board. This diversity enhances the board’s capacity by incorporating a variety of perspectives and specialised expertise.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should be aware that this video may contain images and voices of persons who have passed.

A board might be gender-based. The NPY Women’s Council looks to ‘women’s authority, law and culture’ to deliver their vision and services.2Andrea Mason, “NPY Women’s Council – Governance Acumen,” Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council, published February 2019, [link]

The NPY Women’s Council won the 2012 Indigenous Governance Awards (IGA). In this video, NYP Women’s Council Chairperson, Yanyi Bandicha, and Coordinator, Andrea Mason, explain how their governance works.

Board role and responsibilities

A board looks at the ‘big picture’, rather than the day-to-day management of an organisation, community or nation. It thinks about the future as well as present needs. It works more effectively when all directors have a shared commitment to and clear understanding of these roles and responsibilities. This includes how they work within the group.

It’s also important that board directors understand their role as ethical and honest governing leaders – as well as the legal, moral and cultural responsibilities they have to their group and members.

According to Neil Sterritt, Gitxsan leader from British Columbia, in his Canadian First Nations Governance Handbook, a board carries out four main roles and responsibilities:

Lead

- represent all members and make sure they can take part and be heard

- create vision

- advocate, negotiate and maximise self-determination.

Plan

Set the direction, purpose, future strategies, goals, ethics and values.

Organise

- develop policies and governance arrangements

- interact with management

- steer relationships, alliances and collaborations with the public and among stakeholders.

Manage

Make sure the group is:

- accountable

- fulfils legal, organisational and cultural duties

- hires, supports and oversees the performance of the chief executive officer (CEO)

- monitors outcomes.1Neil Sterritt, First Nations governance handbook: a resource guide for effective councils (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2001).

The following check-up outlines the main roles and responsibilities of a board. Ask yourself whether your board fulfils these roles (pdf, 239KB).

These check-ups are intended for self-directed assessment. They can be used by leaders, board directors, or group members who want to evaluate the governance and leadership of their organisation, community or nation. You can do the check-up on your own or as a group and then compare results.

Board powers and delegations

As part of its responsibility for a group’s governance, the board has the power to delegate some of its responsibilities to someone else. To delegate means to assign or appoint. This delegation is usually subject to legislative conditions. This helps a group to operate effectively and efficiently.

A board can delegate responsibilities to:

- the CEO

- a manager

- a sub-committee

- a director

- a staff member.

For example, the board can authorise a sub-committee to manage the group’s finances. This could include making financial transactions or controlling finances.

When a function is delegated, the board still holds final responsibility for it, and is accountable for what happens.

It’s important to carefully consider what powers and responsibilities a board delegates and to whom. It’s essential that delegations are made properly to avoid risk to your group or the delegate.

Delegations can be challenging in groups where the board doesn’t have the right financial skills. For example:

- When a manager authorises a payment with the belief that it is within their delegation, but the board believes the payment does not align with the group’s policy and strategic goals.

- When a staff member knowingly exceeds their delegation, but it remains undetected because of poor monitoring. For example, if a staff member approves a service agreement that commits the group to spending $150,000 when they know their financial delegation limit is $75,000.

When people exceed the limits of their powers and delegations, issues can arise. For example:

- When senior managers make decisions, spend money or develop governance policies.

- When senior manages set strategic directions without the proper delegation.

- When board members side-step the CEO, instruct staff directly, or interfere in the day-to-day running of the group.

These types of actions can undermine effective governance and confuse staff.

For these reasons, it’s essential that management regularly monitor and report to the board. This includes regular internal and external review, and audits and risk assessment of all delegations.

Record and document powers and delegations

Your group’s key governance documents should outline the board’s delegations and powers. For example, your rule book, constitution and/or policies.

They should define the board, CEO and management’s roles and responsibilities, as well as their powers and delegations.

Good practice for a board

To foster greater stability and capacity within their group, a board can focus on three broad areas:

Leadership

A board should provide positive and confident leadership. It should have a clear understanding of its roles and responsibilities. It should provide strong and capable leadership with a commitment to financial and organisational accountability.

It’s important a board has legitimacy and credibility with its members and external stakeholders. A board should also trust and support management and staff.

Policies and procedures

A board should have excellent manuals, policy documents and other resources to guide them. Board directors should be familiar with these documents.

A board should meet regularly – at least two or three times a year, and decisions should be recorded. It should have ways of resolving the inevitable differences of opinion among the directors, as well as among members or outside stakeholders.

It’s good practice to have terms of office for directors. Generally, only a third or half of leadership positions should be re-elected or nominated on a rotating basis.

When planning for meetings, a board should develop practical quorum arrangements. It should review its own ways of working from time to time so that it’s governing as well as it can.

Management

A strong board has plenty of enthusiasm, teamwork, passion and an accessible, ‘hands on’ chairperson.

A board should make sure management has a clear job description. Directors should review management’s performance annually. It should have regular governance training and sustained mentoring and professional support for board directors and management.

ALPA is led by an all-Yolŋu board of directors from each of ALPA’s five communities: Galiwin’ku, Gapuwiyak, Milingimbi, Minjilang and Ramingining. Two directors are nominated from each community – one a traditional landowner representative nominated by the community’s traditional owners, and one a community member representative nominated by each Community Advisory Committee (CAC).

There is a CAC in each of ALPA’s communities made up of leaders across family groups. The CAC are uniquely positioned to advise ALPA on key areas of community-based concern. Each CAC is representative of the family groups in that community.

All board directors follow ALPA’s Directors Duties and Code of Conduct. This document sets out the responsibilities and expectations of individual directors. Every director agrees to abide by the duties and code of conduct when they’re appointed to the ALPA board. This helps keep their governance strong and ensures all directors understand what is expected.

Board meetings are held quarterly in ALPA’s member communities. Senior management and Yolŋu facilitators also attend board meetings.

In 2022/2023, ALPA’s board was over 80% female. In the 2019/2020 and 2016/2017 financial years, ALPA’s board stood at 67% and 50% female membership respectively.

Strengthen your board

It’s important to notice signs that might show a problem with your board. Below are some of the common problems faced by boards, and solutions to improve your board’s effectiveness.

Strategic direction

The board doesn’t set the strategic direction for the group.

Solutions:

- Have a clearly defined process for setting the direction of your group.

- Make time to discuss strategy in board meetings.

- Make sure directors have the necessary knowledge and experience to guide your group. If any skills are missing, educate them about the strategic process.

Rules, regulations and constitution

The board isn’t making sure that practices or structures follow your rules, regulations or constitution.

Solutions:

- Ensure directors are familiar with your group’s rules and regulations.

- Ensure directors know that following these rules and regulations helps the whole group operate effectively.

- Educate the board about liability and any risks associated with not meeting certain requirements.2Ann Macfarlane, “What if your nonprofit board isn’t following its bylaws?”, Jurassic Parliament, November 2019, [link]

Access to information

The board doesn’t get access to the right information in the right format when making decisions.

Solutions:

- Have an effective flow of information between the CEO and directors.

- Present relevant information clearly and in plain language.

- Make sure the chair provides accurate information at meetings.

Understanding finances

The board has difficulty reading and understanding financial statements.

Solutions:

- Ensure financial information is clear and avoids unnecessary jargon.

- Train your board to read and understand financial reports.

- When necessary, get advice from an external accountant or other financial professional.

Policies

The board is confused over conflict of interest and their code of conduct.

Solutions:

- Educate the board on conflicts of interest and how to manage them.

- Encourage directors to review the board’s code of conduct and ask questions about anything they’re unsure of.

Reviewing decisions

The board approves management’s decisions without understanding those decisions.

Solutions:

- The board should set aside time to discuss key decisions and why they’re being made.

- Directors should ask management for any extra information.

- Directors should not be afraid of asking challenging or probing questions.

Role of the board

The board regularly interferes with the daily work of the management and staff.

Solutions:

- Make sure the board has a clear understanding of its role, and how this differs from management and staff’s role.

- Each board director should have a clear role description.

- The board should understand the importance of separation of powers, and that they are held accountable if they overstep.

Committees

Committees are not engaged in important work and are not coordinated.

Solutions:

- The board should regularly evaluate committees’ performance. They should assess the purpose of committees and what they are trying to achieve.3“Board committees,” Australian Institute of Company Directors, January 2020, [link]

- The board should ensure committee members’ skills, knowledge and experience are appropriate.

- The committee should understand its role and have a clear reporting process.

Communicating decisions

The board does not speak as a united front when they leave meetings.

Solutions:

- Identify why there is disagreement or disunity. If necessary, have a meeting to discuss the issues and keep them from escalating.

- Allow all board directors to have a say and encourage open, frequent communication.

- Remind directors that they should respect the outcome of a decision, even if they don’t agree.

Representation

The board only represents the interests of some of the directors.

Solutions:

- Ensure the board understands their duty to act in the best interests of the group as whole.

- The board should reflect the diversity of the community they serve so they can act in the best interests of all members.

Meeting attendance

Poor attendance at board meetings.

Solutions:

- Board meetings must be accessible for all directors. Is there a need to have meetings online? Are directors given enough warning before each meeting?

- If necessary, develop a meeting attendance policy to encourage regular attendance.

Meeting agenda

The board operates well, but focuses on the wrong issues.

Solutions:

- Ensure board meetings are well managed to avoid discussions going off-topic.

- The chair should understand their role of keeping meetings on track.

- There should be a clear agenda with key issues needing discussion. Directors have access to this information before the meeting.

Running meetings

Poorly chaired and minuted board meetings.

Solutions:

- Give the chair training or support so they are confident in running meetings.

- The board secretary understands how to write clear, comprehensive and unbiased meeting minutes.

- Develop a meeting minutes template.

Board induction

No induction process for incoming board directors.

Solutions:

- Establish an effective board induction process that the chair or a director oversees.

- Provide incoming board members with an overview of their position. Including their roles, responsibilities and any legal obligations.4“Board inductions – bringing on a new board member,” Justice Connect, updated May 2021, [link]

Examples of groups strengthening their board

Here are some examples of what other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are doing to improve the effectiveness and legitimacy of their board:

Tranby National Indigenous Adult Education and Training

All board directors must do ongoing governance training and sector-specific skills development. As a registered training organisation (RTO), Tranby is well placed to provide this training.

Tangentyere Council Aboriginal Corporation

Tangentyere have processes to make sure the board and Town Camp Management Committees represent the community. This includes women, young people and Elders.

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa has a strong Elder leadership structure. This has made it possible to use the skills and knowledge of non-Indigenous ‘advisory directors’ to support Martu governance without undermining cultural considerations. Advisory members don’t have voting rights, but do share the responsibilities of the board. Sometimes advisory directors leave the room so Martu directors can discuss cultural considerations in private.

First Peoples Disability Network (FPDN) Australia

FPDN embodies the notion of ‘nothing about us without us’. Their board is currently made up of five people living with disability. This includes physical disability, psychosocial disability, and intellectual disability. It also includes a parent of a person with intellectual disability. FPDN view their role as custodians of their narratives. This gives legitimacy to decision making on behalf of First Peoples with disability.

Ten opportunities for improving your own board’s effectiveness include:

- Delivering customised experience and training in conflict resolution and peacemaking.

- Providing regular briefings and progress reports on issues that create potential risks or are under dispute.

- Developing policies setting out expectations for codes of conduct, conflicts of interest, and governing roles and responsibilities.

- Developing guidelines for resolving internal or external conflicts, disputes and complaints.

- Training in running productive meetings and making consensus decisions.

- Developing protocols and procedures for grievances and appeals.

- Using the strategic plan, succession planning and future vision as guides for more consistent decision-making and to reduce factionalism and conflict.

- Drawing on the cultural values, input and advice of the wider peer groups of leaders in a group.

- Developing governance charters and manuals for agreed values, rules and commitments.

- Training and creation of a customised process for the board to annually evaluate the performance of their CEO.

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa’s (KJ) governance structure is unique, reflecting its commitment to shared leadership and community-driven decision-making. KJ’s board of directors ensure equitable representation from all four Martu communities along with Martu living off-Country in nearby towns. The board consists of twelve Martu directors and three non-voting advisory directors. Each Martu community is represented by two directors, with a further four representing the Martu who live in Newman and off-Country in nearby towns.

Directors are nominated at a community event and are elected for two-year terms with positions verified at their annual general meeting. This approach ensures the community has a direct say in selecting representatives who reflect their values and priorities. New directors are briefed on the board’s charter and code of conduct during their induction, allowing them to understand their responsibilities and align with the organisation’s governance framework.

Evaluate board effectiveness

An organisation is only as good as its people. Reviewing and building board capacity is as important as reviewing and investing in the CEO’s and staff performance. Implementing effective review strategies and identifying opportunities to build capacity should be priorities.

Because boards, managers and staff work together as a whole to govern an organisation well, then it makes sense to assess how those relationships are going. For example: what is the relationship like between your board and CEO? Between the CEO and their staff? Between the organisation as a whole and its members?

One method is for the board to evaluate its own governance performance annually. This includes reviewing its ability to work and make decisions.

You can do this evaluation internally or externally. There are pros and cons for each. For example, internal evaluation is more cost-effective, but external gives a more independent perspective.

The most important thing is to pay attention to the findings and take action on any areas that need improvement.

So your board can fulfil its role effectively, raise any concerns in a constructive way and decide if any extra support is needed.

This check-up can be used to determine if your board of directors is operating well and are following governance best practices (pdf, 140KB).

These check-ups are intended for self-directed assessment. They can be used by leaders, board directors, or group members who want to evaluate the governance and leadership of their organisation, community or nation. You can do the check-up on your own or as a group and then compare results.

Board skills matrix

A board skills matrix is one tool that can help organisations assess the collective expertise of their board members. It is a visual representation of the diverse skills, experiences, and qualifications within the board, helping to identify areas of strength and gaps that may need to be addressed. The matrix can be used as a resource for succession planning, recruitment, and development of the board. It can help ensure that the board collectively possesses the necessary skills and competencies to effectively fulfill its responsibilities.

Purpose of a board skills matrix

A board skills matrix can be used to:

- Assess your current board composition

- Identify areas for additional skills or expertise

- Plan for succession

- Guide targeted recruitment of new board members

- Ensure effective governance and compliance

- Evaluate board effectiveness

- Support two-way governance

Using a board skills matrix

A board skills matrix is typically organised into a grid format with board members listed along one axis and the skills, competencies, or experience required for the board listed along the other axis. Each board member is then assessed on whether they possess the relevant skill or expertise.

The specific board skills required will depend on your industry, size, and the goals of your organisation, but some common board skills are:

- Industry expertise (e.g., finance, legal, marketing, human resources)

- Strategic planning

- Risk management

- Cultural and corporate governance

- Diversity and inclusion

- Regulatory knowledge

- Technology and innovation

- Leadership or management experience

- International experience

- Stakeholder engagement

- Crisis management

For the board of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander organisation, it is likely there will be additional areas or skill categories to cover. This may include cultural legitimacy and authority, community accountability and two-way governance. Any board skills matrix should be customised to suit your group.

Best practice when completing a board skills matrix

Be transparent: When using the skills matrix for recruitment or succession planning, be open with potential new members about the existing skills, areas of development and what expertise is being sought.

Consider diversity: Ensure that the matrix reflects not just technical skills but also diversity of thought, background, and perspectives.

Use it as a discussion tool: The matrix should not just be a ‘tick the box’ exercise but should serve as a basis for discussions about how to improve diversity, board performance and overall governance. Based on the insights gathered from the skills matrix, you can create a plan or plans that focus on key areas for improvement and development. These plans should aim to:

- Diversify the board: Address areas of under-representation by actively seeking board members who bring diverse perspectives, experiences, and expertise to strengthen governance.

- Enhance skill development: Identify areas where board members may benefit from additional training or development, such as improving communication skills (e.g., ensuring all members contribute concisely) or encourage greater innovation or collaboration.

- Implement succession planning: Develop a succession plan to ensure a balanced board composition, with a spread of tenures to maintain continuity, successful knowledge transfer, and to help with the development of future leaders within the organisation.

Customise for your organisation: Each board will have unique needs. Customise the matrix to reflect the specific skills required for your board to govern effectively in your specific context and industry.

This resource offers a comprehensive skills matrix designed to assess the key competencies and capabilities of your board.

Review the skills outlined in the matrix and evaluate each one based on your board members’ knowledge and experience. After completing the matrix, analyse your responses to identify the strengths within your board’s skill set and areas where additional development or expertise may be required to enhance governance effectiveness.

The Excel template below can be downloaded and edited online.

There is also a simple version of the matrix suitable for printing here: Board Skills Matrix – printable.

Director role

The role of each individual board director is different to the role of the board as a whole. An individual director does not make decisions unilaterally (on their own). Rather, they contribute to the responsibilities, engagement and decision-making of the board as a whole.

A director may have a specific role within the board structure. Typical roles that make up a board are:

- chairperson (or chair, or president)

- deputy chairperson (or vice chairperson, or vice president)

- treasurer (or financial officer)

- secretary

- board specialist committee member

- general board director (or board member).

Each position has its own responsibilities and calls on particular skills.

Depending on the size of your group, some of these roles may be done by non-board members. At the least, every board should have a chairperson.

Whether in a specific role or not, all board directors should represent the organisation’s members and seek their views. They’re also expected to attend and take part in board meetings. As well as contribute their expertise and experience when needed.

Directors must monitor and declare any actual or perceived conflicts of interest. Conflict of interest is a complicated balancing issue that involves both cultural expectations and legislative requirements. We deal with these in more detail below.

Rights of a director

Board directors have important governing responsibilities. They must know the needs and views of their members, understand their group’s business and be active in making decisions about its direction.

Directors also have ‘rights’ associated with their roles. These are documented in the group’s constitution or rule book.

Individual directors generally have the right to:

- attend and participate fully and equally in board meetings

- raise issues and make motions to pass decisions

- speak and debate issues

- vote or come to consensus decisions on issues

- be free from intimidation and threats

- be fully and accurately informed

- be provided with inductions and training on their governance role and legal obligations

- participate in board performance reviews of their CEO

- raise and promote issues of cultural legitimacy and downward accountability to their members.

Responsibilities of a director

Recognising your responsibilities as a director goes with understanding your rights. It can be useful to break these responsibilities down into three areas.

Cultural duties of a director

The cultural duties of a director vary depending on the context and their members and community. However, certain expectations exist at both a local and national level.

As an Indigenous-led group, there’s generally an expectation that directors and the board act in culturally respectful and legitimate ways. This may include:

- acknowledging on whose behalf you have the authority to speak for

- thinking and acting in the interests of your members rather than self-interests

- what issues it’s your place to provide your views on

- who you need to consult before making a decision.

Acting in culturally legitimate ways may involve the culture of the community you represent, as well as the corporate or sectoral communities that your group operates within. It can be a delicate – and sometimes difficult – balancing act to make sure you’re meeting your obligations at these various levels. If corporate obligations conflict with your community’s cultural protocols, you must decide what your priorities are. Your cultural and corporation rules will both provide guidance here.

Not meeting all your duties or obligations as a director may result in dissatisfaction. For example, some choices may meet legal and other obligations, but cause community upset or embarrassment, loss of support, or even removal from the board.

Think about the reasons for your approaches. Be prepared to explain or defend these.

“We try to involve the community in everything the corporation does. The corporation has a board of eight directors and whilst we have the legal authority to make decisions, we involve the community in the decision-making process. Traditionally, decisions always came back to the wider RRK community and different families. We have numerous committees that report to the board, so we approximately have forty representative community members involved in the internal decision-making process of the corporation. It is very important to the board that we involve the community in the process and the community has ownership and meaningful engagement with the corporation. This is an example of how we incorporate Robe River Kuruma traditional governance into our corporate governance.”

– Sara Slattery, Chair, Robe River Kuruma Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC.5Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, Our People, Our Way: Stories of Indigenous Governance Success (Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2020), 36.

Organisational duties of a director

To fulfil your organisational duties as a director, you need a strong understanding of your group. This includes understanding its:

- purpose

- legal structure

- members

- important stakeholders

- funding sources.

It’s your responsibility to make strategic decisions and ensure the group meets their obligations. Directors must also follow the group’s rule book or constitution.

You may have other duties, depending on which legislation your group is incorporated under. For example, for keeping proper records, and preparing and submitting reports to the regulator.

You have a duty to oversee and make sure proper records are maintained and reporting is done on time. Even if you have staff or financial advisors who manage this. You may be held responsible if requirements are not met. Advocacy and engagement on behalf of the organisation is another organisational duty.

If your group is incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), some duties extend to other ‘officers’ in your group. Such as the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, special administrators, liquidators and secretaries.6“Duties of directors and other officers,” Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations, updated 2017, [link]. Check the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) website for more information.

To find out more about the specific duties of directors, check your constitution or rule book and the legislation your group is incorporated under.

Legal duties of a director

Directors must understand their legal responsibilities and duties. These duties have specific conditions and limitations that directors of incorporated organisations must follow.

Ignoring these duties can put you at personal legal risk. You may be found personally liable (legally responsible) for the debts or actions of the group. They can also put directors at risk of losing their cultural reputation and credibility.

Depending on the breach and damage suffered, potential penalties can include:

- fines

- disqualification from acting as a director

- criminal prosecution, which can include imprisonment

- payment of compensation or damages.

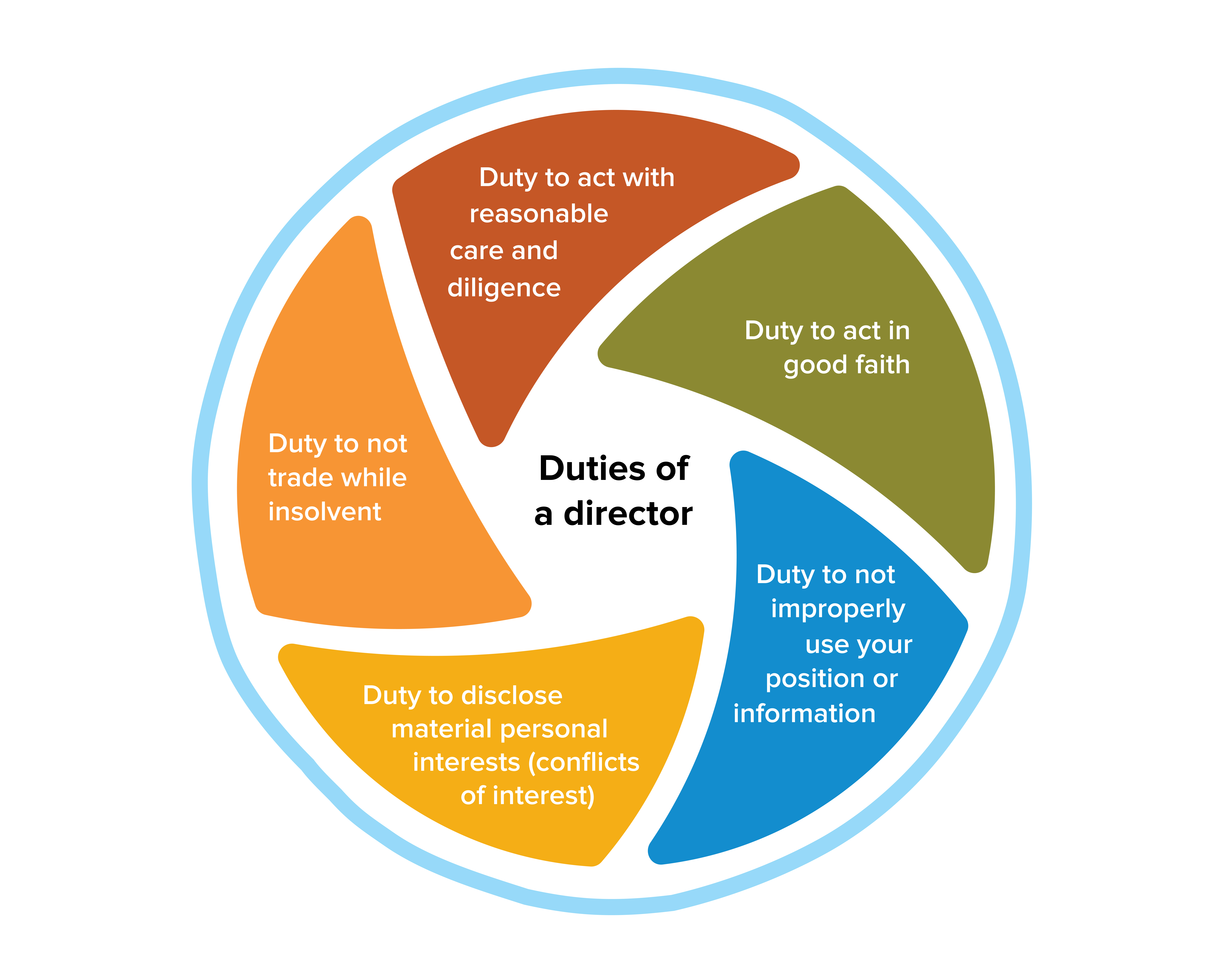

There are five basic legal duties you must comply with as a board director.

1. Duty to act with reasonable care and diligence

Directors must carry out their duties with reasonable care and diligence.

This duty is about the way you do your governing work. This means taking your responsibilities seriously. You must be thorough and prepared to make informed decisions – including about your group’s finances.

To work in this way, you need to:

- read the agenda and board papers carefully before board meetings

- be informed about the group’s activities, and any laws that apply to these activities

- ask tough questions and seek more information if you don’t understand something

- try to attend as many meetings as you can, and stay for the whole time

- be careful when making decisions, and make sure decisions are lawful

- speak clearly for or against any decisions being considered, and publicly support decisions made.

You cannot rely on or outsource your board’s key decisions to people such as consultants, accountants or lawyers. If you follow their instructions without making your own inquiries, you may breach your duty.7“Directors’ Duties,” LegalVision, accessed 2022, [link]

You may be held personally liable (responsible) for the decisions you make. This doesn’t mean that you have to be an expert on everything. It means if you are unclear or confused about an issue, you have a responsibility to get all the information you need to make an informed decision.

2. Duty to act in good faith

Directors must carry out their duties in ‘good faith’ and in the best interests of the group as a whole.

Acting in good faith means acting honestly, openly and fairly. A decision made in good faith is one where you genuinely believe it will benefit your members and the organisation as a whole and not your own personal interests.8Paul Cooper, “What Does the Duty to Act in Good Faith Really Mean?,” LegalVision, updated October 2021, [link]

To comply with this duty, you need to:

- make decisions without bias and in the best interests of the group and its members as a whole – not for self-interest or for particular families, groups or communities above others

- not accept bribes, or involve yourself in any illegal or unethical activity

- disclose to the other directors if you have a personal interest in a decision (a conflict of interest). Collectively, the board decides what involvement you should have in making that decision. The board makes this decision based on the nature of the conflict.

- treat staff, directors, members and stakeholders with courtesy and respect.

3. Duty to not improperly use your position or information

Directors have a duty to not misuse information they’ve gained as a director for personal gain. Or in a way that could be damaging to their group, another director, staff member or group member. You should not use information or your position for any purpose other than the business of your group.

For example, you cannot:

- use your power as a director to reject a membership application because you don’t like that person, even though they are eligible for membership

- unfairly influence the board or management to hire your family members or friends to positions within the group, over other applicants with more relevant skills or experience

- use confidential client information to set up a competing organisation.

You should let the board know if you have a connection with someone that your group plans to hire or do business with. This is called declaring a conflict of interest.

4. Duty to disclose material personal interests (conflicts of interest)

A conflict of interest happens when your duty, roles and responsibilities as a board director conflict with your own personal interests. These could be business, family, or property interests.

For example, where what’s best for you or your family goes against what is in the best interests of the organisation. You may work as a staff member at another organisation, which might positively benefit from a decision you are making as a board member. Or, maybe your brother-in-law has tendered for a contract from your organisation.

Such examples can quickly shift from being potential conflicts of interest to real conflicts of interest if you do not disclose them.

Having a potential conflict of interest does not mean you have done anything wrong. However, if you don’t declare any potential conflicts at your board meeting, then it will be illegal under your organisations’ rules.

A duty to disclose conflicts of interest means being alert to self-serving behaviour. You cannot put yourself in a position where what’s best for you personally or your family goes against what’s best for the group.

If you have a potential conflict of interest, the right thing to do is to disclose it – this means tell other people about it. By disclosing the conflict, you’re being transparent. Whenever you notice an agenda item that you think might present a potential conflict of interest, declare what your interests are at the beginning of the board meeting or when that agenda item comes up for discussion.

Organisations often keep a ‘conflicts of interest register’. This lists any staff or director’s conflicts of interest. This can help oversight and transparency.9“General duties of directors,” Australian Institute of Company Directors, May 2020, [link] Often, the chairperson will open the meeting and ask other board members if they have any potential conflicts of interest to declare. Everyone then gets the opportunity to discuss their potential conflict/s and have them put on the ‘register’.

The advantage of this is that potential and actual conflicts of interest are not always easy to tell – so it can be helpful to talk about it with your fellow board directors. It’s always best to raise an issue and discuss it, rather than ignore it.

When you disclose a conflict of interest, the board can decide how it should be managed. For example, you may not be able to vote on the issue yourself (abstain), and you may need to leave the room when they discuss the issue.

A conflict of interest can arise when you:

- have a direct or indirect interest that conflicts with or influences the performance of your duties to the group you govern

- start to intervene in the everyday management of your group to get a friend or relative employed, or to get special treatment or favoured access to particular resources

- vote on a matter that helps your own business, or makes it harder for your competitors to compete with you in the marketplace

- vote on a land ownership or land use issue that increases the value of your property to the detriment of others

- are in a position to benefit a friend or relative as a result of your position, when this benefit would not otherwise be available to them (this is often called indirect conflict of interest)

- fail to declare any of these potential conflicts of interest. For example, one of your family members may submit a tender to do paid work for your group. When this happens, the elected member should let everyone on the board know that they have a potential conflict of interest. The board can then decide how that conflict should be managed.

Taungurung Land and Waters Council in Victoria point out three main sources of conflict of interest:

Relationships

Relatives are board directors. Or there are relationships between a board director and a staff member. Or relationships between staff and other stakeholder organisations.

Conflicting roles

For example, when a board director is also a potential recipient of a payment or a position, or has a direct relative who is a potential beneficiary.

Personal gain

When a board member stands to gain personally from a decision – financially or in some other way.10AIATSIS, Toni Bauman, Belinda Burbide, TLaWC and Chris Marshall, Decision-making Guide (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and Taungurung Land and Waters Council (Aboriginal Corporation), 2019), [link]

For more information on conflict of interest, including steps to take to declare and manage conflict of interests, see the Taungurung Land and Waters Council decision-making guide on the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) website.

5. Duty to not trade while insolvent

Directors have a duty not to trade while insolvent. This means they must not allow their group to continue trading (operating) if it becomes insolvent. A group is insolvent when it doesn’t have enough money to pay all its bills when they are due. Directors also have statutory duties in relation to financial record keeping and reporting.

To comply with this duty, make sure you:

- are fully informed about the group’s financial position

- ask questions if you don’t understand something about the financial statements and reports presented in board meetings

- get training on understanding financial statements if you’re unsure of the basics, and ask for plainly written summaries of financial risks

- bring in auditors or financial experts if you need a second opinion on financial records

- do not make a decision or authorise a transaction that causes the group to become insolvent.

Directors may be liable for the group’s debts if they allowed it to trade while insolvent.

Other legal duties

You may have other legal duties to comply with, depending on the legislation your group is incorporated under and the type of group you are. For example, under the CATSI Act, a prescribed body corporate (PBC) has additional regulations regarding decision-making processes.

For high level native title decisions, the PBC must consult with the common law native title holders and obtain their consent. The PBC must use a traditional decision-making process if one exists. For instance, if decisions were traditionally made by Elders, the PBC must follow this same process.

If no traditional decision-making processes exist, native title holders must agree on an alternative process, such as voting, a nominated individual making the decision, or the PBC directors making the decision.

Consequences of breaching director’s duties

The consequences of breaching your duties depend on:

- the nature of the duty breached

- the seriousness of the breach

- what damage might have been suffered as a result.

If an action carried out by a director was authorised by the organisation’s constitution or rule book, a decision passed at a board meeting or a general meeting of members, there may be no breach of the director’s duties.11Mark Harley, “Breach of director’s duties,” Boss Lawyers, accessed 2022, [link] However, it depends on the facts of each breach. You should seek legal advice if you think you, or another director, may have breached their duties.

Consequences for breaching your duties include:

- loss of trust and credibility with the members

- reputational damage to the organisation, board, and director in question, which may have commercial consequences – for example, loss of funding or clients12“General duties of directors,” Australian Institute of Company Directors, May 2020, [link]

- being removed as a director by the organisation

- being formally disqualified from managing an organisation– this means you cannot act as a director for any organisation

- being compelled to pay or compensate the organisation or others – such as creditors – for any loss or damage suffered as a result of the breach

- being convicted of a criminal offence, which may attract a fine or imprisonment

- being found guilty of a civil offence, which may also attract a fine or disqualification.

Chairperson role

The chairperson (or chair) role is held by a board director. Some organisations have created innovative arrangements to better suit their needs. For example, they:

- have co-chairpersons – two or more people sharing the chair role

- have a chairperson and deputy chairperson

- have a different director playing the chairperson role at each meeting

- bring in an external expert as an ‘ex officio’ or ‘observer’ board member– this person provides advice to the chair or full board, but may not always be able to vote in board decisions.

The chairperson’s role is very important to effective and legitimate governance. They chair board and annual general meetings (AGMs). They are a public spokesperson or representative for the group. They may also have responsibility for ‘signing off’ or authorising some board activities.

The chairperson is like the head coach of the football team. They are an experienced leader who brings everyone’s individual skills together. They encourage players to play as a team, develop new skills and kick the winning goals.

An effective chairperson:

- leads the board

- is ‘in charge’ of running board meetings and making sure board directors behave according to meeting rules

- helps steer the direction and performance of the group

- earns the respect of other members of the board, and the broader group

- listens to everyone in the meeting and does not dominate board meetings with their own opinions

- encourages every person to express their views, ask questions, vote and help make decisions

- makes sure decisions are fair, relevant and of a high standard

- initiates effective governance practices within the board

- mediates when conflict arises

- promotes good relationships within the board, among members and with the community

- acts as a role model and promotes high standards of behaviour and practice

- makes sure that full, accurate information is provided at meetings.

Chairing a meeting requires confidence, skills and training – it doesn’t just happen. When an experienced, confident chairperson runs a meeting, things run smoothly.

Neil Sterritt says:

“How often have you been asked to chair a meeting only to realise you do not know how? You are not alone. This is a common problem for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people who have been elected or appointed to councils or boards.”

– Neil Sterritt, Old Massett Village Council Governance Reference Manual

It’s important that your chairperson is prepared and supported in the role. This includes regular training for board directors so they have the skills to chair a meeting. They should have regular opportunities to hone their practice.

The benefits of having a well-practiced, confident and skilled chairperson include:

- better discussion

- efficient use of meeting time

- informed decision-making

- no one being excluded or left out

- valuable ideas are heard

- previous decisions are followed up

- outcomes are achieved

- a shared spirit of cooperation and achievement among board directors.

The deputy chairperson (or vice-chair, or vice-president) can step into the chairperson role, if needed.

The secretary is responsible for organising meetings, record keeping and maintaining documents.13“New to a board or committee? An introduction to your role,’ Justice Connect, updated May 2021, [link]

Effectively chairing a meeting

To be an effective chairperson, you need to prepare and have a good understanding of how to run a meeting.

Here are some tips to effectively chair a meeting:

Be prepared

Think about the purpose of the meeting and what outcomes you’re aiming for. Also consider:

- what discussions are needed

- who needs to be there

- what information needs to be provided (possibly in advance) for this outcome to be reached.

Include an agenda that other board members can contribute to, and distribute it in advance.

Set the tone

Set the tone of the meeting by welcoming all and acknowledging Country. Make known any meeting rules, and consequences for not following these. Motivate directors to participate and have their say. Make sure everyone present has the agenda and any other documents they need.

Follow processes

Make sure discussions are relevant to agenda items and keep agenda items on time. Introduce and conclude each item to make sure it’s clear that the meeting is progressing. The minutes should reflect this progress.

Follow and guide processes for decisions. Each process should be documented.

Make sure rules of meeting are followed. Manage uncooperative or disrespectful meeting attendees. Make sure everyone has a chance to be heard for each item.

It’s not your role to impose your views in a meeting. You’re there to facilitate, not to dominate.14“Chairing a meeting,” Resource Centre, published November 2007, [link]

Chairing difficult board meetings

As a chairperson, you’ll have to manage competing interests and different personalities. Dealing with difficult people can be challenging. But with the right strategies, you can navigate these situations and create solidarity. For example, if an argument starts or someone is being overly critical, you can:

- remind people of the rules for respectful behaviour and shared cultural values

- be firm and consistent when applying the rules

- allow people to have time out if discussion becomes too heated

- summarise the points made by each person and then ask others in the meeting for their thoughts

- ask the critical person for their suggestions on what they think should be done about it, and then get the views of others

- ask everyone in the meeting for support – for example, ‘Do people want more time to keep discussing this issue or would you prefer to move on?’

A good chairperson makes sure everyone gets a say. Your job is to encourage participation and discussion. Even people with unpopular views should have the chance to be heard. You may need to invite those who are shy or uncertain to share their views. Or you may need to limit the talking time of some people. No one should feel intimidated for saying what they think.

There’s always room for improvement. To learn how you can improve the way you chair a meeting, think about your leadership style as a chair and ask for feedback from meeting attendees. For example, after the meeting, ask them what they thought went well or what could have been done differently. Or encourage attendees to give their feedback on a form at the end of the meeting.

Other board member roles

Other board members may have specific duties to fulfil, depending on their role. We discuss some common board director roles below.

Deputy chairperson (vice-chair or vice-president)

The deputy chair will step in as chair as required, and may be delegated some of the chairperson’s work in an ongoing way.

Treasurer

The treasurer’s primary role is to manage the finances of the organisation. This means keeping the finances ‘healthy’ and keeping track of how much organisation owns, where money is going and its main sources of income.

It is the responsibility of the treasurer to:

- ensure other directors understand the organisation’s financial obligations

- advise the board on financial matters, including potential opportunities or risks

- review internal financial reporting processes

- keep financial records up-to-date.

Secretary

The secretary is responsible for organising meetings, record keeping and maintaining documents. They fulfil the administrative duties of the board. The secretary role can be taken on by the CEO or a dedicated staff member of the organisation.

Their role includes:

- recording minutes at each board meeting

- distributing relevant documents to other directors

- scheduling and preparing board meetings

- creating meeting agendas and recording attendance.

Ex-officio board member

An ex-officio board member is someone who holds a seat on the board because of their position, usually because they need to have a say in the organisation’s decision making. This may be the chief executive officer, chief financial officer and chief operating officer.

Unless the organisation’s constitution or rulebook state otherwise, ex-officio board members usually have voting rights and are able to be counted as part of the quorum.

Board committee member

Sometimes, boards may delegate work to committees that members of the board serve on. These committees then make recommendations for action to the board. Usually, the majority of committee members will be independent non-executive directors. Committee members will have different roles and responsibilities, depending on the type of committee they are on.

Some common committees include:

- audit committees

- renumeration committees

- nomination committees

- risk committees

- fundraising committees

- executive committees

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

Stay connected

Subscribe to AIGI news and updates.

.png)