To help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations understand what Data Sovereignty means and why it matters...

Self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

In this topic, we explore the concept of self-determination and how it applies to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We introduce nation building, treaty and development as examples of self-determination in action.

While reading this topic, think about the following questions and how they relate to your organisation, community or nation:

- What does self-determination mean to you and your group? Why is it important?

- Are there ways your group is already making self-determined decisions?

- How does your group understand sovereignty?

- What does self-determination have to do with nation building, treaty and development?

Understand self-determination

The ongoing impacts of colonisation mean that self-determination is particularly important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. With self-determination, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups can make their own decisions about their governance and the kind of group they want to build.

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, self-determination means having genuine decision-making power and responsibility about what happens:

- on their lands and waters

- in their affairs

- in their governing systems

- in their development strategies.

When thinking about self-determination, it might be useful to consider these phrases:

- ‘First Nations people in charge’

- ‘We make the decisions’

- ‘In the driver’s seat’ or ‘steering our own course’

- ‘Being in charge of our own destinies’

- ‘Community-controlled health organisations and other services’.1Jackie Huggins, Karrina Nola, Larissa Baldwin and Kirsty Albion, Passing the Message Stick (Get Up, Original Power and Australian Progress, 2021), 78, [link]

The word ‘self-determination’ itself is an important reflection on what it means – and has meant – for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples throughout history.

Self-determination

Before colonisation, there were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations. The ‘self’ in self-determination was the nation as a collective and culturally based polity. A polity is a group of people who work together and operate as one political group.

Self-determination

With colonisation came efforts to terminate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations. Settler-colonial states attempted to extinguish the collective identity of groups and remove their links with Country. In other words, they tried to reduce the ‘collective self’ of First Nations to ‘selfish’ (individualistic) determination.

Self-determination

Then followed an era where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations fought for rights and recognition. They were able to determine their own collective identities and futures.

Self-determination:

Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations are working to implement the rights they have won. They are working to rebuild and exercise collective decision-making authority, to self-govern as nations again.

– Adapted from Diane Smith, Developing Governance and Governing Development, 2021.2Diane Smith, “Governing for Nation-Building, Thematic Introduction: Concepts, Issues and Trends,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 111.

Self-determination and sovereignty

Sovereignty is a concept that is talked about a lot by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia today. But what does it mean?

Sovereignty is closely tied to self-determination:

“The terms ‘sovereignty’, ‘self-government’ and ‘self-determination’ are often used interchangeably to describe the political aspiration of Indigenous people to have more control and say in the issues that affect their lives.”

– Larissa Behrendt, First Australians.3Larissa Behrendt, “Self representation, self-determination and sovereignty,” in First Australians, ed. Cathy Hammer, (Sydney: Legal Information Access Centre, 2013).

In simple terms, sovereignty is about the authority and autonomy of a group to govern its own people and jurisdiction.

Sovereignty means Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups have the right to make their own informed decisions. They can choose their own ways of governing themselves, within the nation-state of Australia. A nation-state is a geographically bounded group of people who identify as a nation.

Sovereignty also includes the right to preserve their different collective identity and cultures.

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, sovereignty today means that absolute power over their community lies with the community itself. Not somewhere else.

Sovereignty is a power commonly claimed by nation-states. It was historically asserted by settler colonial states – such as Britain – when they took over the lands of Indigenous peoples. The sovereignty of a nation-state is given power – or legitimacy – through being recognised by other nation-states at an international level. For example, through the United Nations.4Alessandro Pelizzon, “General Principles of Sovereignty for non-lawyers,” National Unity Government, accessed 2022, [link]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples often talk about sovereignty in different ways:

“Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.”

– Uluru Statement from the Heart, 2017.

Uluru Statement from the Heart

The Uluru Statement from the Heart describes the sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as an ancestral, spiritual relationship to the land.5Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017 : Uluru, N.T.), authorised by Geoff Scott, The Uluru Dialogue, Kensington, [link];The wording used in the Statement comes from the judgment of Judge Fouad Ammoun of the International Court of Justice in 1975 in the Western Sahara Case: [link]. This understanding of sovereignty is different to what’s understood in western law.

Within nation-states across the world, certain groups continue to claim that they hold or exercise their own sovereignty. This situation exists for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today.

In international law, there are specific ways in which sovereignty is recognised as being acquired or taken. Colonisation in Australia happened without any treaties with or payment to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This was justified by the British Empire on the legal fiction of terra nullius. In other words, on the basis that Australia was ‘empty land belonging to no-one’.6Marcia Langton, “Sovereignty: 65,000 years of ancestral links to land,” Agreements Treaties and Negotiated Settlements, written for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney 2020, [link]

In 1992, the Mabo case was brought by Eddie Koiki Mabo, Reverend David Passi, Celuia Mapoo Salee, Sam Passi and James Rice. The case overturned the legal fiction of terra nullius.7Mabo and others v. Queensland (No. 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 F.C. 92/014 (3 June 1992); “Mabo and Native Title,” Australians Together, modified August 2022, [link]

The passing of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) followed the Mabo case. This legislation provides a process for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to seek recognition of their traditional rights and interests over land. To learn more about the Mabo case, see Mabo and Native Title on the Australians Together website.

Overturning terra nullius means that Australian law recognises that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a prior claim to land taken by the British. As a result, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been rightly asking: Where is our treaty? Where is our sovereignty? To learn more about treaty, see Nation building, treaty and development.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia today believe their sovereignty was never ceded – or given up. They continue to fight for recognition of this fact. Many are calling for recognition of their sovereignty within the nation-state of Australia.

“While acknowledging its inadequacy, the notion of ‘sovereignty’ may be the closest term in English able to portray the obligations to country and community that Aboriginal Elders and leaders describe.”

– Daryle Rigney, Simone Bignall, Alison Vivian, Steve Hemming, Shaun Berg and Damein Bell, Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building, 2021.8Daryle Rigney et al., “Treating Treaty as a Technology for Indigenous Nation-Building,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 123.

Strategic sovereignty

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty is not recognised in land rights and native title legislation in Australia. Instead, these laws and processes involve the sovereign power granting rights to some members of the Australian nation-state. In Australia, the sovereign power is the ‘Crown’.

The rights granted are still subject to the authority of the sovereign power. In other words, broader laws of the nation-state limit what you can do on native title land.9Alessandro Pelizzon, “General Principles of Sovereignty for non-lawyers,” National Unity Government, [link]

Although sometimes limited, traditional owners and native title holders are finding these sometimes limited co-existing ‘rights’ offer a strategic way to leverage and negotiate other opportunities. They are using many different, legal, political and economic rights – however limited – to push the boundaries of their sovereign authority.

Increasingly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are taking part in their own conversations about how to assert greater agency, autonomy and self-determination. In doing so, many groups are finding innovative ways to exercise greater control over their governance arrangements. For example, through:

- entering agreements or contracts that steadily help to increase their financial independence

- building strong mechanisms for local control of decision-making or dispute resolution

- designing culturally-legitimate governance solutions that centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge systems and ways of governing.

We call these tactics ‘incremental self-governance.’

There are many ways Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, communities or nations can exercise incremental self-governance. As Diane Smith explains,

“In Australia, examples of incremental governance-in-action include the renegotiation of group identities and intergroup relationships; entering into agreements and contracts on joint ventures and partnerships with external stakeholders; resolving cross-boundary and membership issues; designing workable policies, regulations, and structures; and redesigning governance models and constitutions.”

– Diane Smith, From Little Things, Big Things Grow: Exercising Incremental Self-Governance in Australia, 2019.10Diane Smith, “From Little Things, Big Things Grow: Exercising Incremental Self-Governance in Australia,” in Reclaiming Indigenous Governance: Reflections and Insights from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, eds. William Nikolakis, Stephen Cornell and Harry Nelson (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2019), 135-137.

Some groups are achieving incremental self-governance by working to prioritise a single project that delivers practical and meaningful changes, before moving to the next project and so on. These projects do not have to take place on a large scale, or even with the legal rights and recognition of external governments.

Where possible, groups are gaining greater control to govern their own affairs, in ways of their choosing, and then building from that. In this way, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations, communities and nations are exercising their sovereign authority.

Achieving self-determination

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights to self-determination have been ignored or undermined, or acknowledged or modestly supported over the years. Still, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ desire to govern themselves – and to build their capacity to do that well – persists.

In 2016, applicants to the Indigenous Governance Awards were asked the following question: How does your organisation demonstrate self-determination?11Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards, (Canberra: Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2018, Prepared by A. Wighton), 52.

Analysis of their responses reveals many elements are central to achieving self-determination. These elements are more closely related to the self-determination of organisations. However, they also apply to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, communities and nations.

The elements are often interrelated, as described by Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation:

“[Effective Indigenous leadership and self-determination] is demonstrated by our organisational structure, from our all-Indigenous board, the way we make decisions, [to] the values and culture of our organisation. We have good Aboriginal employment levels, and most importantly, we are ensuring that Aboriginal people have the opportunity to have their voices heard and are telling their own stories. That is self-determination.”12Australian Indigenous Governance Institute and Reconciliation Australia, Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards, (Canberra: Australian Indigenous Governance Institute, 2018, Prepared by A. Wighton), 52.

The elements identified as key to achieving self-determination include:

Leadership and succession planning

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership for self-determination means Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have genuine control over:

- their decision-making

- their projects

- their solutions for nation (re)building.

In an organisation, leadership for self-determination could mean Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples having decision-making power at the board, operational and/or program level. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations today aim to keep a majority Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander membership on both their boards and in operational staff.

“[You need a leader] … that is able to demonstrate big ideas, bigger picture, kind of way of thinking … But also somebody who’s able to look at the human factor, and have demonstrated experience of being able to build capacity of people in community … I think really, the biggest thing is being able to communicate with people. And if you can’t do that, then you’re not going to be successful.”

– Participant 7, Interview, Indigenous ‘Elder’ Organisations: Resilient adaptive governance and management as a capability for longevity and renewal.13Mia McCulloch, Lara Drieberg, Diane Smith and Francis Markhim, Indigenous ‘Elder’ Organisations: Resilient adaptive governance and management as a capability for longevity and renewal, (Discussion Paper No. 300/2022), Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, 2022, forthcoming.

Groups taking a nation-building approach are also recognising the key role played by their cultural leaders. Any substantial, long-term change for nation building must be led by dynamic and passionate nation ‘rebuilders’. As Debra Evans and Donna Murray explain:

“We have had the privilege of culturally centred leadership from important and highly respected Wiradjuri elders who explain and model yindyamarra in how they live and the values they embody. They also embody self-determination in their actions and in the way they fulfil their responsibilities to Wiradjuri country, culture and community.”

– Debra Evans and Donna Murray, Culturally Centred, Community Led Wiradjuri Nation-Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way.14Donna Murray and Debra Evans, “Culturally Centred, Community Led: Wiradjuri Nation Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 179.

Autonomy

Autonomy is not just about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples having control over their lives. It is also autonomy over decisions to manage and care for Country.

Achieving autonomy means greater control over:

- community matters

- development

- the way land and resources are used.

The Yawuru Ranger Program – established with the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ (DBCA) Parks and Wildlife Service – allows Yawuru people to actively manage their own country. Yawuru rangers are involved in the management of introduced species and uncontrolled fires. They are also working with scientific experts and Elders on a geospatial mapping tool to improve land use decision-making. These opportunities to work on Yawuru country allow Yawuru to exercise their native title rights and regain control of their land – an exercise of autonomy.15Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation: Activating cultural assets for economic growth and stability,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 244-245.

Setting the agenda

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups need to set self-determined priorities and initiatives.

For many groups, self-determination includes setting the agenda through advocacy. This is often achieved through:

- media campaigns and presentations at public events

- participating in forums

- commissioning and/or publishing research

- forming relationships with industry leaders

- collaborating with a range of Indigenous community leaders, community-controlled organisations, service partners and external stakeholders.

“My work in the context of Indigenous self-determination could be said to have been possible only through my project remaining independent, thereby as an Indigenous operator I have had the freedom to be entirely self-determined. This independence, while incredibly difficult at times, has allowed the development of a project that is purely an Aboriginal Australian culturally unique model.”

– CEO, Australian Institute of Loss and Grief, Indigenous Governance Awards Analysis, 2016.

Consent and decision-making

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) recognises the right to free, prior and informed consent.

Free means there is no coercion or influence.

Prior means Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are consulted before any activity is carried out on their lands or territories.

Informed means Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are provided with all available information. They are informed when information changes or new information is made available. If Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not understand the information given, they have not been informed.

Consent means there has been honest consultation, full and equal participation, and respect of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditional decision-making processes.16The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Free Prior and Informed Consent An indigenous peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities (United Nations, October 2016), 15-16, [link]

Free, prior and informed consent is an expression of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ right to self-determination.

For example, for native title holders entering into mining agreements, self-determination is about having access to – and understanding – all the information they need to give free and informed consent – before approving any project that affects their lands or waters.

Capability building and investing in expertise and knowledge

Capability building is the development of an individual or group’s core skills and abilities to build their overall effectiveness and achieve their goals. Capability building also means Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can better identify issues that may impact their ability to achieve their desired outcomes and gain the insights, knowledge and experience needed to solve problems and implement change.

There are many ways to build the capabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to achieve their self-determined goals. In the work of Wiradjuri nation building, Donna Murray and Debra Evans explain how capturing the knowledge and expertise of their Elders has been a self-determined decision:

“As part of this Wiradjuri journey we are now working with other community members on the collection and collation of our stories and maintenance of their cultural and intellectual property. We are part of a group that has set up a non-profit publishing company. This is another act of self-determination in ensuring that we respect, identify and support our elders in sharing their knowledge and expertise.”

– Debra Evans and Donna Murray, Culturally Centred, Community Led Wiradjuri Nation-Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way.17Donna Murray and Debra Evans, “Culturally Centred, Community Led: Wiradjuri Nation Rebuilding through Honouring the Wiradjuri Way,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 183.

Strategies that organisations have implemented to support this theme of self-determination include:

- targeted employment and retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander directors, CEOs and staff members

- training and development opportunities for the board, staff members and future leaders

- implementation of culture-smart policies for a culturally secure workplace.

An analysis of Indigenous Ranger Programs across Australia highlights the importance of rangers having access to relevant training and skills development. In Arnhem Land, for instance, the Yirralka Ranger program focuses on “formal training and skill development with the ultimate goal being to have local Yolngu people in all positions.”18Katie Bellchambers and Jason Field, Governing Country: A literature review of Indigenous governance principles in Indigenous Ranger & Protected Areas Programs (Discussion Paper No. 300/2022), Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, 2022, forthcoming.

Culture-smart governance solutions

An example of self-determination in action is being culture-smart with your governance. This means incorporating core cultural values and culturally informed practices into your governing arrangements.

Cultural-smart governance solutions are about people determining together what kinds of cultural authority, decision-making, leadership, and collective identity they treasure and value. When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make their own decisions about what the core cultural values and practices for their governance processes should be, they are exercising self-determination.

“We recognise that the journey to recovery and self-determination will only be successful if we incorporate a great and real appreciation for our cultural traditions and beliefs. We create and structure our working environment and programs around Indigenous knowledge and worldviews.”

– Marninwarntikura Fitzroy Women’s Resource Centre, Category A Finalist, Indigenous Governance Awards, 2016.

Effective and legitimate governance

For organisations, effective governance for self-determination plays a role in many contexts, including:

- forming and structuring the board

- overcoming challenges

- the affect and effect of projects and programs

- partnerships and stakeholder engagement

- communication and decision-making.

“We know that effective governance is an ongoing process that involves a huge number of elements on operational and strategic levels … We have Annual General Meetings that run smoothly and engage our community. We are currently performing very well and feel confident in our ability to keep moving forward and serving our community, but are aware that we need to keep checking on ourselves, our processes, our community feedback and our vision. We hope to keep working closely with our community, maintain our high standards and ensure that our mabu liyan framework continues to be communicated and used into the future to ensure we can deliver on our promise of sustainable and culturally connected prosperity for everyone in our community.”

– Yawuru Corporate Group, Joint Winners Category A, Indigenous Governance Awards, 2016.

For First Nations, governance for nation building is most successful when it’s seen as being culturally legitimate by members. Peter Yu explains how centering the ‘mabu liyan’ philosophy – a guiding principle for the Yawuru – was key to the effectiveness and legitimacy of Yawuru nation building. Mabu liyan is a central part of Yawuru cultural values and practices. It describes the interconnectedness between people, culture and country.

“Following our native title determination, the message from our community was clear: rebuilding the social and cultural fabric of our society had to be a priority focus. We need to recover and strengthen mabu liyan and incorporate this philosophy, handed down by our ancestors, into all our development strategies for the future. In that way, we know that our development initiatives will reinforce, not undermine, our ongoing cultural resilience and maximise our self-determination.”

– Peter Yu, Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation: Activating Cultural Assets for Economic Growth and Stability.19Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation: Activating cultural assets for economic growth and stability,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 245.

Community engagement and voice

A strong relationship with community is central to self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups. Members of an organisation, community or nation should have equal opportunity to express what kind of governance they want, and what kind of group they want to build. They have to be able to express a self-determining voice in those collective decisions.

To align their goals and initiatives with self-determined community needs, organisations need participatory processes, consultation and connection with the community. These connections can also be fostered by engaging community members in the organisation. For example, as staff, directors, project participants, volunteers, organisation members and partners.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations showcased their capability for adaptive self-determination. They effectively governed through the pandemic by modifying their governing and operational arrangements. An important element of this was keeping communities informed and giving them equal access to clear information. Organisations achieved this through posters, written formats, videos and social media.20Lara Drieberg, Dale Sutherland, and Diane Smith, Governing the Pandemic: Adaptive Self-Determination as an Indigenous Organisational Tool, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, 2021, forthcoming.

“Our organisation is run and owned by the local Aboriginal community. All Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people who reside in the local area are eligible to become a member of Minimbah and to have a say in how it is run.”

– Minimbah Preschool Primary School Aboriginal Corporation, Category A Shortlisted Applicant, Indigenous Governance Awards, 2016.

Financial independence

Self-sufficiency is a key means of working towards self-determination. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are creating their own income sources for self-determination.

The importance of financial independence for self-determination has emerged in a context of political change and federal funding uncertainty. For some organisations, reducing reliance on external funding has meant they can redirect funds back into their communities. For example, through self-funded programs and paid participation for members at training, meetings and other events.

Peter Yu explains how Yawuru used their native title determination to support the economic development of the Yawuru Nation:

“In return, the Yawuru received monetary benefits for capacity-building, preservation of culture and heritage, economic development, social housing, and joint management of a conservation estate comprising conservation areas along the coast and a marine park covering much of Roebuck Bay. The agreements also provided land to the Yawuru for their own development and cultural heritage purposes. Yawuru’s objective in negotiating the agreement was to have a secure basis for income generation and to limit the influence of the state in the management of our affairs. We were also having to respond strategically to a rapidly changing economic environment in our region and identify the next steps to our future stability and self-reliance.”

– Peter Yu, Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation: Activating Cultural Assets for Economic Growth and Stability.21Peter Yu, “Rebuilding the Yawuru Nation: Activating cultural assets for economic growth and stability,” in Developing Governance and Governing Development: International Case Studies of Indigenous Futures, eds. Diane Smith, Alice Wighton, Stephen Cornell and Adam Vai Delaney (Maryland: Rowan & Littlefield, 2021), 238.

For more detail on these elements, see Strong Governance Supporting Success: Stories and Analysis from the 2016 Indigenous Governance Awards.

Self-determination in action

If self-determination is the right and authority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups to control their own affairs, then governance is how that right is exercised.

Self-determination means different things to different groups, and there are many ways Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are gaining greater control over their lives and affairs. Many groups are focusing on:

- enhancing their capacity to effectively govern treaty negotiations

- enacting their rights as sovereign nations

- increasing their self-determined development.

Not all groups will embark on a journey of nation building or engage in treaty making. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are focusing on having control over the types of development. Or gaining full decision-making authority over how land or resources are used.

What this means is that there are many views about how to best achieve self-determination.

Treaty making

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are focusing on treaty making as a way to exercise their self-determination.

According to First Peoples – State Relations Victoria, “treaty is the embodiment of Aboriginal self-determination. Treaty provides a path to negotiate the transfer of power and resources for First Peoples to control matters which impact their lives.”22“Treaty in Victoria,” First Peoples – State Relations Victoria, reviewed December 2022, [link]

Nation building

Other groups have begun a journey of nation building as a way to achieve self-determination. For many First Nations, self-determination is at the heart of nation building. Self-determination is what enables Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to choose and control their respective governance models and the way they want to live their lives. At the same time, having effective and legitimate governing structures in place is crucial if Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations are to realise their self-determined goals.

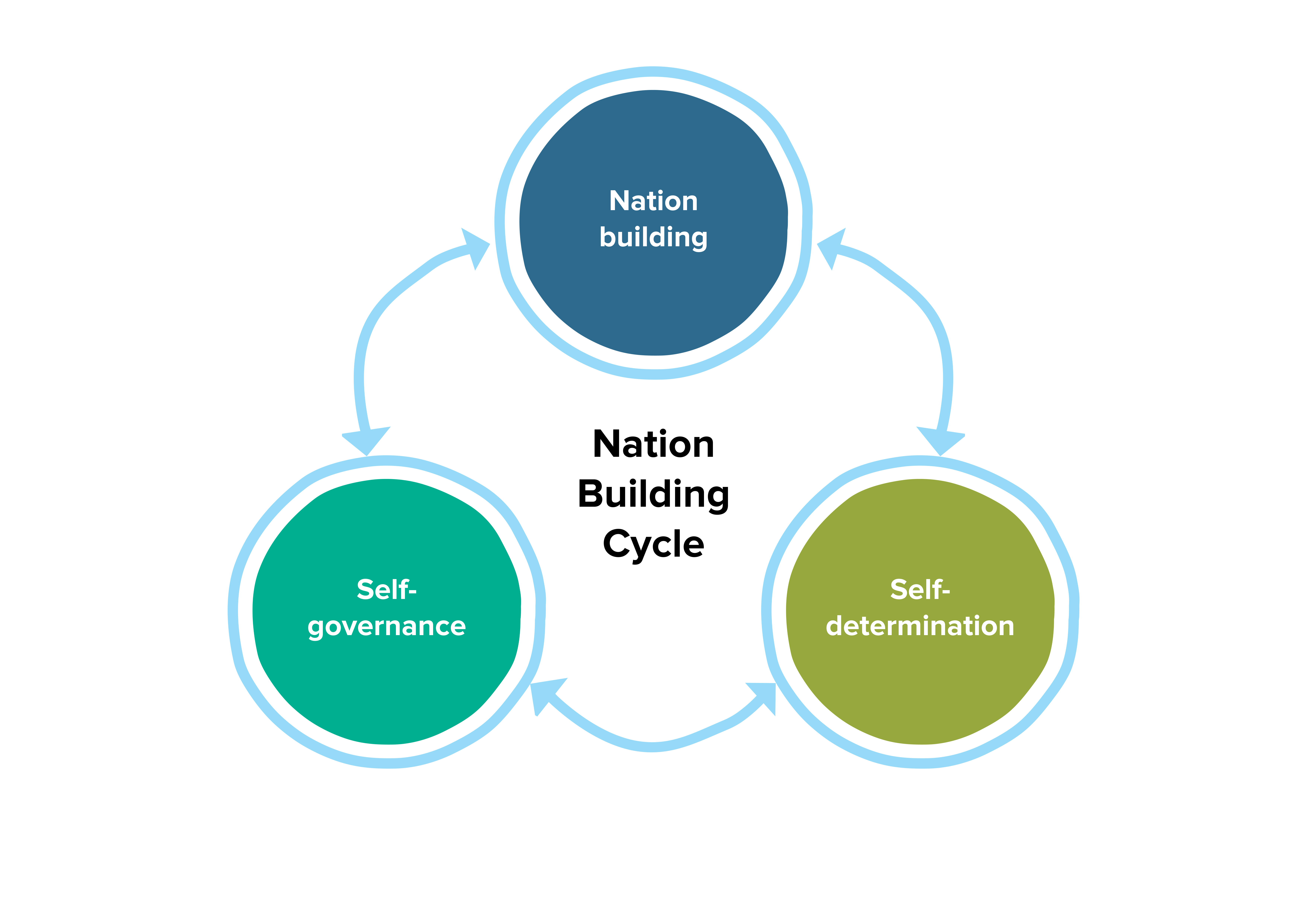

In this sense, we can view nation building, self-governance and self-determination as an interrelated cycle.

Development

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups are focusing on having control over the types of development in their group, or gaining full decision-making authority over land or resource usage.

A review of literature relating to First Nations prosperity, economic development and wellbeing points to two predominant views about the link between self-determination and development:

- Self-determination and autonomy are an “outcome of economic development and prosperity”.

- Self-determination is needed for development.

In other words, self-determination and development reinforce one another – the more you have of one, the easier it is to obtain the other.23Annick Thomassin, Maggie Elmitt, Mandy Yap and Kirrily Jordan, Exploring Economic Prosperity for Aboriginal Peoples in New South Wales: Review of the literature, Report to Aboriginal Affairs NSW (Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, 2020).

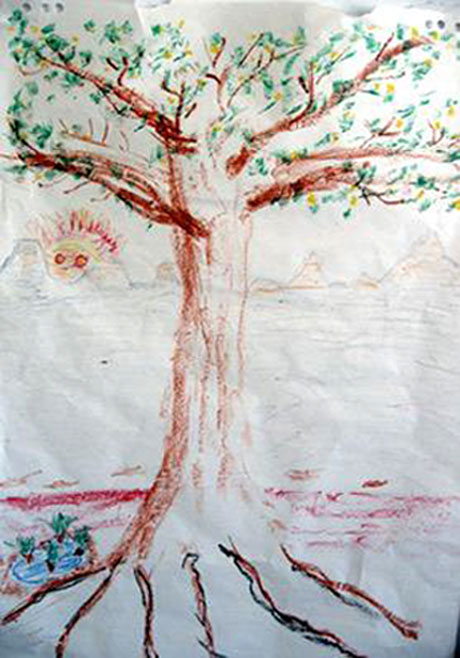

“Strong tree, strong people, strong culture.

The sun, the leaves, the branches, the flowers, the seeds, the water and the bark are all parts of governance.

The trunk of the big tall tree is an elder passing on knowledge and wisdom. The bark covers the trunk and holds it together.

The branches are networks. The yellow leaves are the old people who need to be looked after.

The seedlings in the waterhole are the young people listening to and learning from the elders, who are watching and supporting them.

The sun is looking to see who’s going to be a strong leader in both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. This system provides strong governance – everything’s inter-connected, allowing the tree to provide good fruit.”

– Illustration and story by participants at the “Sharing Governance Success Workshops” of the vision for their strong future governance, 2007.2Sharing Governance Success Workshops, held in 2007 in Sydney, Port Hedland and Mt Isa. An example workbook from the Mt Isa workshop can be found here: https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/Workbook_Mt_Isa.pdf

Self-determination and international law

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) recognises Indigenous peoples’ inherent right to self-determination. UNDRIP was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007.24UN General Assembly, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295, [link]

Below is an extract from UNDRIP:

Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions.

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their rights to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic, social and cultural life of the State.

Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right to belong to an indigenous community or nation, in accordance with the traditions and customs of the community or nation concerned. No discrimination of any kind may arise from the exercise of such a right.

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision-making institutions.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to determine their own identity or membership in accordance with their customs and traditions. This does not impair the right of indigenous individuals to obtain citizenship of the States in which they live.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to determine the structures and to select the membership of their institutions in accordance with their own procedures.

Indigenous peoples have the right to determine the responsibilities of individuals to their communities.

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) has been translated into Pintupi-Luritja.

Australia signed and endorsed UNDRIP in 2009. UN Declarations are not legally binding on any country, unless the provisions are put into domestic law or policy. For example, in Canada. However, countries who have signed the UNDRIP are expected to honour and advance its provisions.25“International Human Rights Law,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, accessed 2022, [link]

The 2014 Social Justice and Native Title Report argues that nation building in Australia should be guided by UNDRIP to help “lead to the realisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights, stronger communities and more meaningful engagement.”26Australian Human Rights Commission, Social Justice and Native Title Report 2014, 112.

UNDRIP is particularly relevant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups who are building self-determined governance. It suggests they have the right to experiment and be innovative in their governing arrangements.

It also encourages a transition away from a focus on external governments and solutions to internal creativity and strengths. This process can be kick-started through:

- internal yarns about collective identity and relationships

- strategies to revitalise the participation of group members

- considering the valued role of culture in future modes of governing

- focusing on rebuilding prioritised institutions (the rules of governing).

The common feature across these strategies and pathways is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are driving the momentum themselves.

“MWRC was founded by women asserting their rights to self-determination … today, the women continue to advocate, locally, nationally and internationally for their community’s rights as Indigenous peoples.”

– Marninwarntikura Fitzroy Aboriginal Women’s Resource Centre Category A Finalist, Indigenous Governance Awards, 2016.

We’ve translated our extensive research on Indigenous governance into helpful resources and tools to help you strengthen your governance practices.

Stay connected

Subscribe to AIGI news and updates.

.png)